Peyi Soyinka-Airewele, professor and chair of the Ithaca College Department of Politics, has worked with many students of color, both as a mentor and through providing mental-health support. However, as one of the few faculty of color on Ithaca College’s campus, she said she is often overburdened by mentoring requests.

This is an issue that many faculty of color experience across the country — a form of “cultural taxation.” Psychologist Amado Padilla coined the term in 1994 to describe ethnic minority faculty’s obligation to serve the college’s diversity needs while also not receiving institutional recognition for this extra service, especially when the taxation impinges on the responsibilities that are required for achieving tenure or promotion. Thus, it is a price faculty of color pay in service to the academy.

At the college, African, Latino, Asian and Native American faculty make up 11.6 percent of the population, and ALANA students make up about 20 percent of the student population, according to the Office of Analytics and Institutional Research. This disproportion of faculty of color to students, as well as to other white faculty members, often requires them to take on more responsibility, such as being called to be the diversity representative on committees and to advise and mentor ALANA organizations and their students. Other faculty of color have said they provide mental-health support to students of color on campus, as many students have said they were not able to find help elsewhere on campus that reflected their distinctive experiences as students of color.

Soyinka-Airewele referred to the taxation as a “creeping killer.” She said that when she began mentoring students of color, there was excitement and joy at the prospect of connecting with these students. But as she focused on her commitment to this workload, she said, it escalated far beyond the level of normal responsibilities.

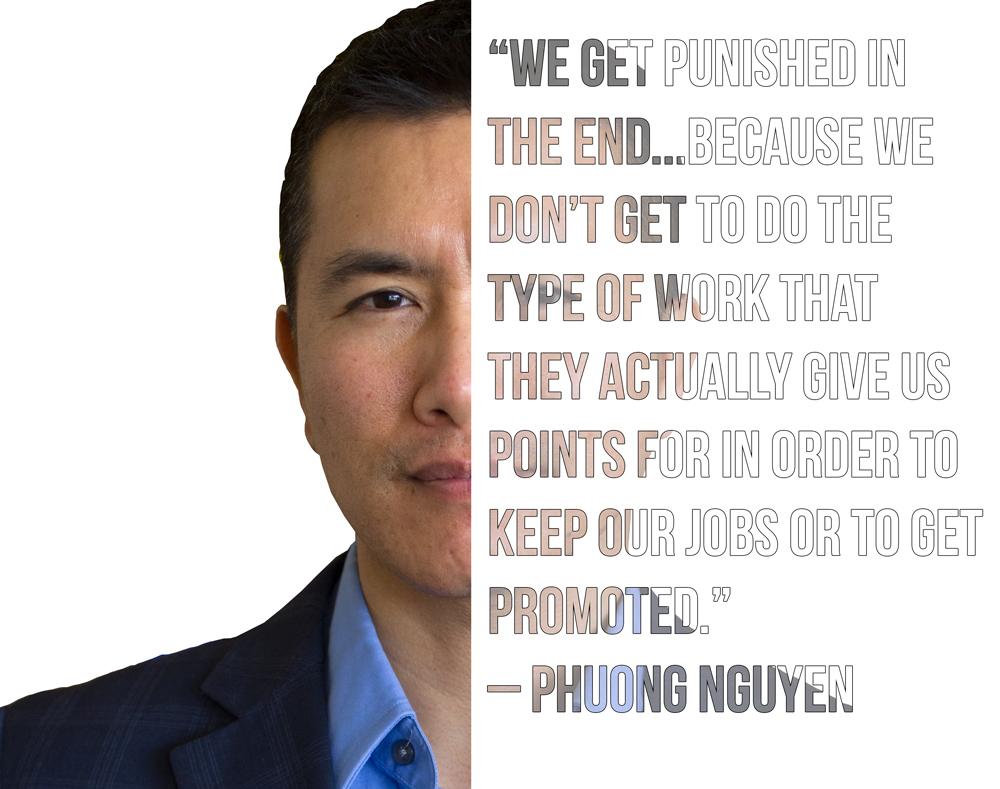

Phuong Nguyen, assistant professor in the Center for the Study of Culture, Race and Ethnicity, said he takes on extra responsibilities serving as the faculty mentor for the Asian American Alliance and the China Care Club, in addition to working on the Pan Asian American Film Festival and the Vietnamese Association at Cornell University — service he said he willingly takes on because he feels an obligation to serve the community. However, he said the college will not weigh that service any more heavily when reviewing him for tenure.

“We get punished in the end for it because we don’t get to do the type of work that they actually give us points for in order to keep our jobs or to get promoted,” Nguyen said.

Brad Hougham, chair of the All-Tenure and Promotion Committee, said the criteria for tenure and promotion as stated in the Ithaca College Policy Manual are teaching excellence, scholarly research or professional attainment, and service to the institution. Service can include any volunteer-based work through serving on committees, mentoring students, or advising clubs and organizations. Hougham said that among the three criteria, teaching excellence is the most important, followed by scholarly attainment and finally, service.

“If someone isn’t an excellent teacher and if they don’t have any attainment in their profession, they’re not going to get tenure,” Hougham said. “It doesn’t matter how great their service is.”

Nguyen’s focus on this extra service, he said, has taken time away from his scholarly work, personal life and preparation time for classes. His book is set to publish this fall, but the only times he can conduct research are during the spring and summer breaks. The work has gotten so overbearing, he said, that faculty in his department had to tell him that his performance was slipping in his other responsibilities and that he needed to step back from the service work, like keeping up the CSCRE social media.

“We don’t want these things to collapse, but we can’t let our careers collapse as well,” Nguyen said. “So there’s this kind of tension between the individual and the collective.”

He said he especially feels guilty if he has to turn away students who seek him out personally.

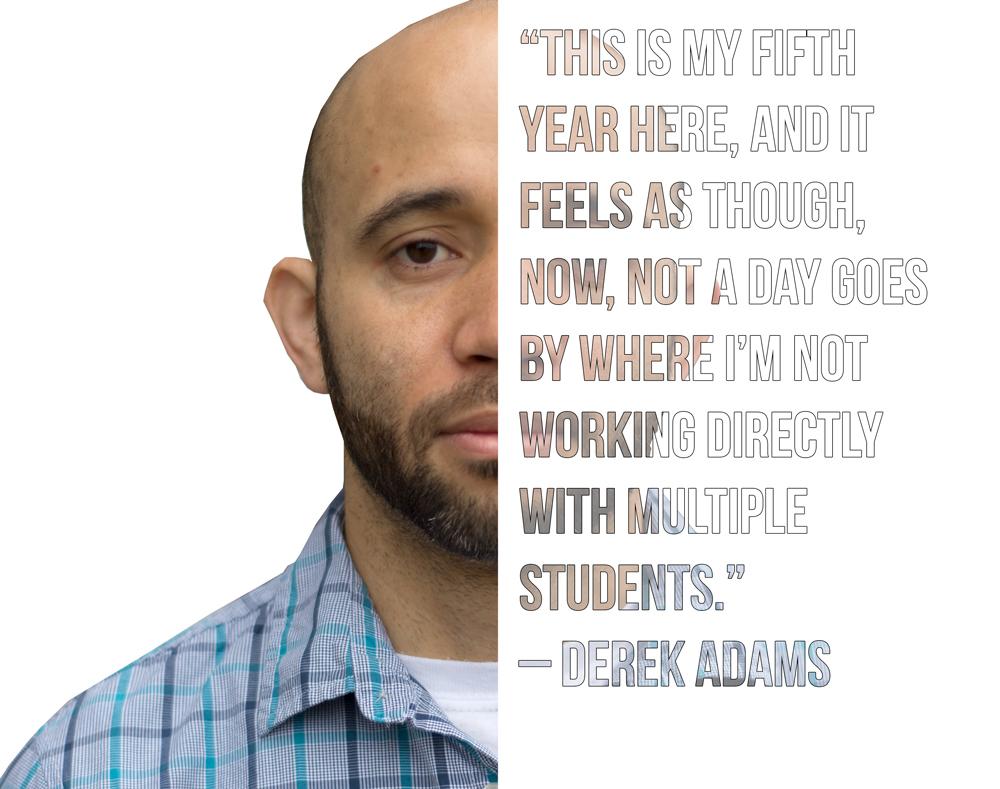

Derek Adams, assistant professor of English, said one of the reasons he gets to connect with students is because he represents diversity at a college that is not very diverse and that the students recognize this. However, he said the nature of his student mentoring has changed in that the number of students he mentors has grown beyond just students of color — to the point where he said he cannot count the number of students he works with.

“This is my fifth year here, and it feels as though now, not a day goes by where I’m not working directly with multiple students,” Adams said.

Sophomore Alexa Ubeda, a mentee of both Adam’s and Soyinka-Airewele’s, said that because of this, it can be difficult to schedule meetings with them, though connections with them have benefited her academically and personally as a student of color.

“[Soyinka-Airewele] said it’s her job and that’s what she’s here for, but I feel bad sometimes because there are a lot of students of color that go to her,” Ubeda said.

Freshman Ally Vasquez said she does not have any mentors of color at the college but that she wishes she did. She said making a connection with a white professor is not impossible but that it would be more difficult for her than for her white counterparts because of the racial difference.

“It’s unfair,” she said. “I’ve seen white students who have really great connections with their white professors, and I wish I could have that kind of a connection with one of my professors.”

Adams said the reason he got into this profession was to be able to make connections with students, but the service has been taxing not only on his time, but also on his emotions. Speaking with the students who participated in the demonstrations of the POC at IC movement in 2015 was particularly emotionally taxing, he said.

In the Fall 2015 Semester, after a string of race-related incidents including allegations concerning Public Safety officers’ making racially insensitive comments, the exclusive and also racially insensitive comments made by J. Christopher Burch ’76 at the Blue Sky Reimagining Kick-Off event, and the racially themed party thrown by the off-campus fraternity Alpha Epsilon Pi, POC at IC formed to protest the lack of diversity and inclusion on the college’s campus.

On top of the influx of mentoring requests these professors of color have received, Soyinka-Airewele said multiple students have expressed to her that the college does not offer enough mental-health help, particularly for students of color. Senior Hadiza Kassim said it is hard to find help with mental-health struggles in a predominantly white college because the personal experiences people of color have can have a great deal to do with their race and ethnicity.

“For some people, it’s not that they don’t want to be there for you, but there’s a disconnect if they can’t really understand,” Kassim said. “They can console you, but can they relate to you?”

Soyinka-Airewele said that during the protests in 2015, students of color were desperately in need of mental-health services, but the services available to them were not necessarily attuned to what these students were facing.

“One student was literally on the point of a breakdown because of the mounting anxiety from the threats they were encountering,” Soyinka-Airewele said. “She went to see a CAPS counselor. According to her, the counselor was dozing off while she was talking.”

She said students of color need counselors who understand the sociocultural ways in which they express their needs and distress without having to be told what it is like to be in their shoes on this campus.

CAPS has approximately 1,000 clients a year, and about 200 of those clients identify as people of color, said Paul Mikowski, a psychologist in CAPS. Based on CAPS’ satisfaction surveys, he said, there is no indication that students of color who use their services are dissatisfied. He said CAPS welcomes any feedback from the community regarding improvements it can make to better support students of color.

Currently, the main service available specifically for students of color at CAPS is “Being” Skills & Process Group. Jacque Washington, a social worker in CAPS and a woman of color, said she created “Being” this spring.

Washington said she created this group because when she began working at the college, she wanted to help students of color at the college. Because “people of color” is such a broad term, she said, she wanted to create a group to specifically address struggles students who identify with the African diaspora.

The main directive of “Being” is to teach students skills such as distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, mindfulness and emotion regulation, and how to use those skills in certain experiences they may face as people of color within the diaspora, Washington said. She said there are usually eight people in a group, but it currently has six active members.

“I do plan to do another group with those skills and open it up for everybody, but I wanted to do that specific population to start off with,” Washington said.

Mikowski said CAPS also has a general group program that is available to any student and that there are students of color who participate in the program. He said CAPS does try to be inclusive.

Apart from Washington, Mikowski said he knows of one other counselor, Leah Murphy, who identifies as a person of color, but that providing a number is difficult because he does not know everyone who identifies as a person of color.

Freshman Antonio Mim said the issue is not just about getting more people of color but about teaching everyone in the community how to communicate with people of color.

“I’ve met some white people here who just don’t know how to communicate with a person of color, and I think that’s something that needs to change, too, in order to make the situation better,” Mims said.

Vasquez said it is not only important to have more people of color at the college but to educate white professors in a way so they can better understand and connect with students of color.

Whenever Kassim is struggling with her mental health, she primarily reaches out to her work supervisor, a person of color with whom she said she has a good relationship. When she struggles academically, she said, she feels comfortable reaching out to her professors in the Gerontology Institute.

Matt Mogekwu, associate professor and chair of the Department of Journalism, said students of color need to go to people who can understand their stress from perceiving the college’s environment as unaccommodating in terms of resources for them.

“Unfortunately, here … there are not many people or mentors of color whom students can go to for support,” Mogekwu said. “That’s why some of us are taking it upon ourselves. We know that sometimes students cannot come, so we go to them.”

Mogekwu said he has been serving as the adviser of the Park Association of Journalists of Color for the past five years. He said this is an extra responsibility but that he does not complain about it.

“I accept it with equanimity, with the understanding that I’m doing some good and to that extent that I’m doing some good that I don’t need to complain,” Mogekwu said.

However, he said he has not seen the college recognize any of the extra work faculty of color often do at the college.

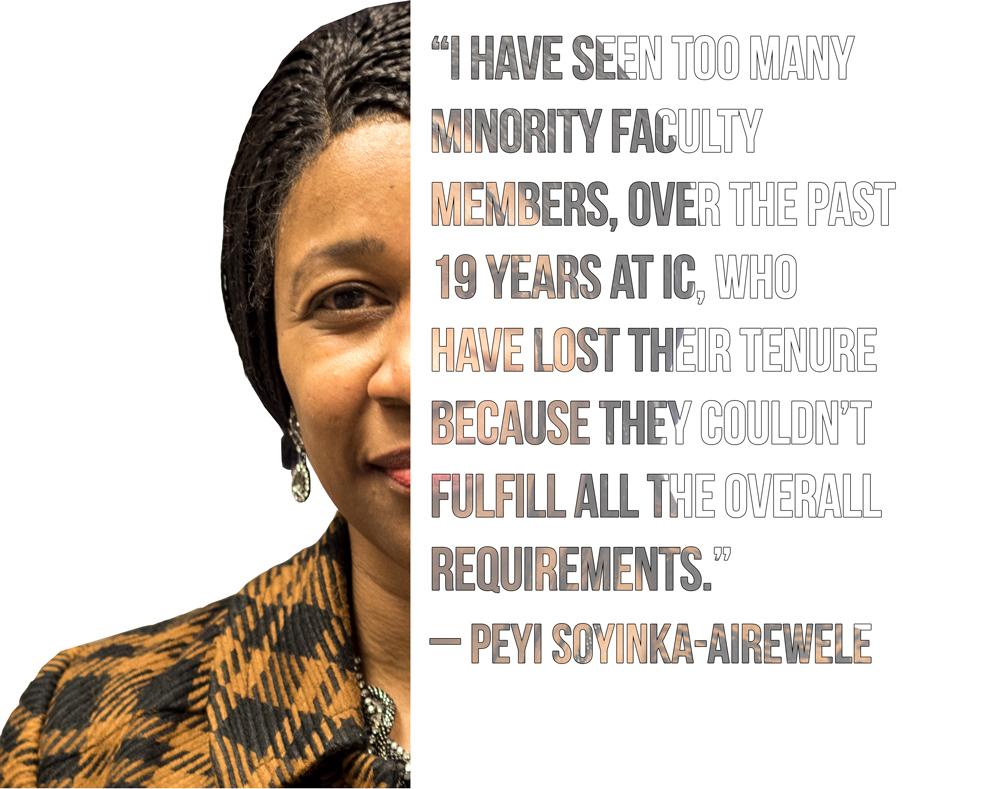

Soyinka-Airewele said she agreed and that she has experienced faculty of color not being able to keep up with the extra service work.

“I have seen too many minority faculty members, over the past 18 years at IC, who have lost their bid for tenure as they sought to fulfill a range of expectations,” Soyinka-Airewele said. “That’s because they were carrying three times the burden of their colleagues for this area of service that was unrecognized.”

Roger Richardson, associate provost for diversity, inclusion and engagement, said he believes people in the community are aware that cultural taxation exists but that the challenge is figuring out how to qualify and acknowledge those faculty members who do extra service.

“It is an important issue, but I think trying to qualify it would be even more difficult because I think everybody — whether you’re a majority faculty and staff member or a faculty and staff member of color — contributes the best they can,” Richardson said.

Adams also said he does not know if there is any way the institution could recognize the extra service.

“How could you explain the emotional thing that happens in a space like this on a form that you turn in to the administration or to your department chair?” Adams said. “How do you put a value on that?”

Hougham said there should be a way to recognize outstanding service but that recognition may not be in the tenure and promotion process. Because the college relies heavily on service from faculty, he said, there should be an institutional award recognizing publicly this extra service.

Linda Petrosino, provost and vice president for educational affairs, said the college prioritizes teaching excellence in particular when evaluating faculty and that service is not weighted as heavily.

Petrosino said she has seen trends in faculty of color doing more service work, specifically in the area of student mentoring. She said she believes faculty of color see it as their responsibility to engage in mentoring and modeling students but that the administration wants those faculty members to be successful in all three areas.

“I think it’s about having a conversation with faculty about how to serve our students — about how to attempt to carve out time so that attention can be paid to the teaching and the research components because we very much need our faculty to be successful and to be here after tenure for our students who need them,” Petrosino said.

She said the college could help faculty of color select service work by helping them understand the time commitments, giving them the permission to decline requests to serve on certain committees and helping them balance their service with teaching and research so it is not so burdensome.

“The harder piece, I believe, is the advising piece,” Petrosino said. “I don’t know of a faculty member who will turn a student away.”

However, she said she does not have the “magic answer.”

“I think it’s an important issue for us, and I think it’s an issue that’s probably not going to go away,” Petrosino said. “I think it’s important to recognize it and try to find ways to help our faculty to be successful.”