A phenomenon known as the “silo mentality,” which has pervaded both higher education and corporate culture for decades, has affected Ithaca College, where a notable separation exists among the five independent schools.

While this mentality manifests in a historical separation of curriculum development among schools at the college, a growing number of students are breaking from traditionally distinct schools and prescribed majors, aided by expanding programs with similar goals, such as the planned studies program and the Integrative Core Curriculum.

Silo mentality is an attitude that can be found most commonly in the business sphere when divisions resist interdepartmental interaction, which can inhibit free-flowing communication. Don Capener, dean of the Davis College of Business at Jacksonville University, said silo mentality began to affect colleges and universities in the 1930s and ’40s when academia moved toward specialized programs instead of cross disciplinary–based–educations.

Capener cited a disconnect between faculty and administration that led to the creation of the silo mentality at the collegiate level. This disconnect is detrimental to college students’ education and limits students’ ability to think broadly and creatively, he said.

“What happens is you have inefficiency, but you also have poor leadership and decision making,” Capener said. “Who suffers? The students and the faculty. Rather than silos being a catalyst for student success, they are actually an impediment.”

Fostering communication among faculty members is a goal of the Center for Faculty Excellence at the college, CFE Director Wade Pickren said. He said the reason there is a silo mentality at the college is due to the structure of the administration with each school overseen by its own dean.

“We have a traditional liberal arts core, the school of [Humanities & Sciences], and then we have four professional schools that surround that,” Pickren said. “We’re not just one educational unit here. This is what sets up a silo structure. It’s not some intentional, malicious thing at all. Schools are just set up to deliver what they are here to deliver.”

Nick Kowalczyk, associate professor in the Department of Writing, said he thinks this structure results in a lack of communication among faculty members.

“The institution has basically chosen to have five little fiefdoms of miniature bureaucracies all underneath the umbrella of an ever-growing top bureaucracy,” Kowalczyk said. “That’s a naturally dysfunctional setup … it’s like I live in Rhode Island and someone in the journalism school lives in California.”

Kowalczyk said he saw the effects of the silo mentality at the curricular approval process — more specifically, when he developed a new non–fiction writing course, a class that was in his job description when he was hired. Course ideas are developed at the department level, evaluated by the school’s administration and, finally, evaluated by the Academic Policies Committee, he said. When the course Kowalczyk developed got to the Academic Policies Committee, the group of faculty members and administrators in control of voting on curriculum said it was blocked by a dean outside of H&S.

“I had worked so hard trying to get a class on the books, that was literally in the job description that I had applied for, and it was being held hostage because somebody from the other silo didn’t like the fact that we were creating this class,” Kowalczyk said. The class was later approved.

Diane Gayeski, dean of the Roy H. Park School of Communications, said she does not think there is a silo mentality at the college, and said that if it did exist, it would not affect the APC process or the development of classes co-taught by faculty from different schools. She said there are some administrative hurdles for setting up classes that are co-taught, such as figuring out where the credits get counted, but there are processes for creating co-taught courses.

She said she thinks the size of the college accounts for students’ feeling like they do not know everything that is going on because there is so much happening on campus at all times.

“But I can certainly understand from a student’s point of view that it may seem difficult to know what’s happening in lots of other majors,” Gayeski said.

Mary Ann Erickson, coordinator of integrative studies and associate professor and chair of the Gerontology Institute, said one effect of having a silo mentality at the college is that faculty members feel they cannot advise outside of their school because of a lack of understanding regarding other schools, she said.

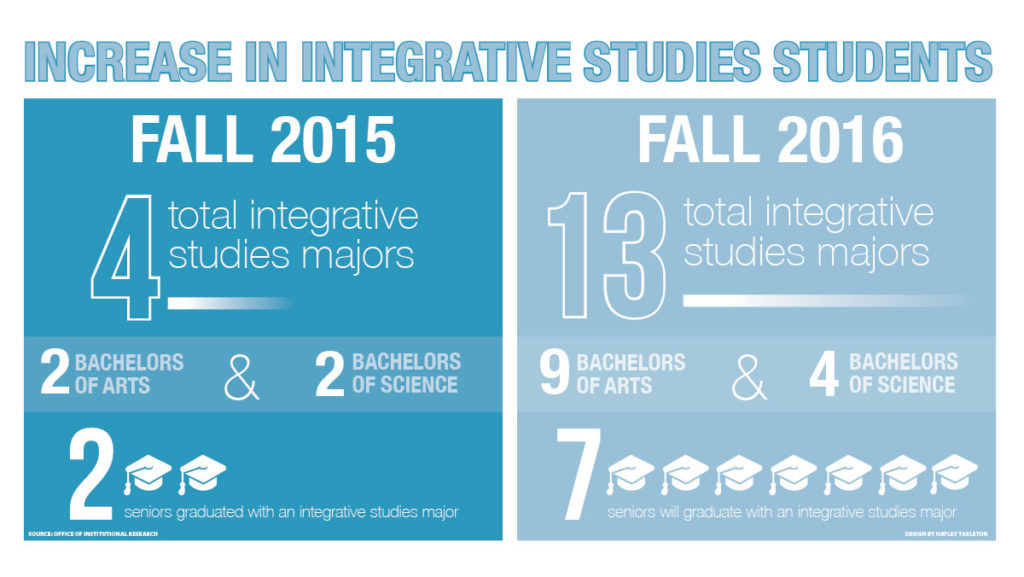

But enrollment in the integrative studies program, formerly known as the planned studies program, has increased dramatically from previous years. Students in the program develop personal curricula with the help of faculty advisers from each department that their plans envelop. This year, there are 13 students enrolled in Integrative Studies overall for Fall 2016 — nine B.A.’s and four B.S.’s — compared to two of each during Fall 2015, according to the Office of Institutional Research. In 2014, there were also four students enrolled, and in 2013, six. The program is housed in the School of Humanities and Sciences and coordinated by a group of nine faculty members and associate deans who specialize in a diverse group of disciplines.

Rachel Reuben, former associate vice president for marketing and communications at the college and contributing writer on the subject of the silo mentality for Inside Higher Education, said the first step to breaking down silos at the collegiate level is to improve communication.

“If a school is silo-ing itself because it doesn’t feel like it is a part of a larger communication plan or they’re not being communicated with … they feel they are getting slighted and want to go off and do their own thing,” Reuben said.

Erickson said she thinks the silo mentality at the college has decreased in her 16 years here, and she credits the Integrative Core Curriculum, the Integrative Studies program and the first-year seminars.

“I think that there is an opportunity for programs like Integrative Studies or the Ithaca seminars to tear down, hop over, decrease the silo mentality, as we in each school get to know each other’s programs better and get to see potentials for collaborations with students,” she said.

Senior Melanie Bryant also said faculty need to do more to break down the silo mentality.

“I think that it would be helpful if professors looked into different things that are going on in different schools,” she said. “I think that professors don’t know exactly what is going on in different departments. I don’t know if there is a lot of communication on that end.”

Pickren credits IC 20/20, the college’s all-encompassing vision for its academic, civic and financial goals that will conclude in 2017 for beginning to break down the silo mentality at the college. He said he has seen an increase in cross-school communication between faculty since its implementation.

The center sets up programs to bring faculty members together, such as faculty learning communities, which involve faculty reading the same higher education–related book and discussing ideas relevant to the college. Pickren estimated that around 18 percent of faculty members from multiple schools took part in at least one learning community last year.

To get rid of the silo mentality at the college on the faculty level, Pickren said, there needs to be an effort from the deans of the schools.

“There would have to be deliberate programs that would really encourage the deans to actively find ways for their faculty to collaborate across the school boundaries, across the silos,” Pickren said. “It would take more than we could do here. It would take the deans’ actively being involved. It’s going to take a little time for us to get there.”

Contributing writer Rachel Kreidberg contributed reporting to this article.