Daniel Ellsberg transformed American war politics in 1971 after releasing the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret study prepared by the U.S. Department of Defense that shed light on the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967. Since then, Ellsberg has remained an advocate for independent media and government activism.

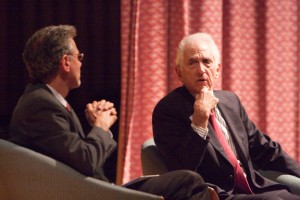

Ellsberg spoke to students, faculty, staff and the public last night in Ford Hall after a screening of the Oscar-nominated documentary “The Most Dangerous Man in America,” which chronicles the events leading up to the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

Before his speech, Ellsberg spoke with News Editor Aaron Edwards about the Obama administration, student activism and journalism in the 21st century.

Aaron Edwards: What do you think is the value of independent media today?

Daniel Ellsberg: You get a kind of comprehensiveness about certain subjects that you’d never have gotten from one newspaper or two newspapers. There’s no question that you get an awful lot more news and more angles of the news from being able to read accounts from many different papers. You see commentators like Glenn Greenwald on Salon.com — he’s almost my guru on matters of civil liberties, and he’s also a very good critic of the press.

I see more analysis of the defects and shortcomings of the mainstream media in particular than I ever have seen before since the days of George Seldes and his successor I.F. Stone. It’s a complement to the daily press.

AE: You recently spoke out in support of Bradley Manning, a U.S. Army soldier who allegedly leaked more than 90,000 pages of Afghanistan documents to WikiLeaks. How should an organization like WikiLeaks handle publishing materials that reveal government and corporate misconduct?

DE: WikiLeaks did well to bring in The New York Times, Der Spiegel and The Guardian to look over the material they had on these Afghan logs and coordinate with them instead of just putting it out. If they just put it out on the Internet, it was so much material that I don’t know who would have read it.

AE: What are your thoughts on the level of interest students have when it comes to issues in politics and journalism?

DE: Some students do tell me over the years that there’s been a great decline in concern about politics. There’s much less activism. In fact, [activism] is often seen on the right, as we’re now seeing with the tea party off campus. But even on campuses it seems that right-wing groups are more active.

Why don’t we see as much activism on campuses now? I’ve never been entirely clear. I’m told that students feel they have to concentrate more on their careers and keeping their academic credentials. Of course, the general mood of the country from President Ronald Reagan was more focused on making money and careers. Generally, I don’t know why there’s such a striking contrast between the youth of the ’60s, who really did want to change the world, and students of today.

AE: What about when President Barack Obama was elected? It seemed like students were highly invested in his campaign and showed strong political involvement.

DE: I can’t blame them for being disillusioned. I wasn’t as hopeful as a lot of people were for Obama. I campaigned for him and did some fundraising, and I, of course, voted for him, but I did not foresee the likelihood that he or any other major candidate would greatly roll back the civil liberties abuses that Bush had instituted.

I don’t think that any president willingly forgoes powers that have been bequeathed to him by his predecessor. I did not foresee that he would get out of Iraq, even though he’s promising to do so. When Obama says we’re going to have all the troops out of Iraq by the end of 2011, I think he knows that isn’t true, and he’s consciously deceiving us on that.

He roped a lot of people in, especially young people, and they really did expect “change you can believe in.” He hasn’t delivered on that in the slightest respect. And the question is, did he ever really expect to? Or was it just a slogan?

AE: So with all this lack of public scrutiny on the mainstream media and government, is there really any hope for American politics in this generation?

DE: [Laughs]. As much as people despise the idea of a lesser evil, the truth is that some evils are worse. The worst is really a lot worse, and it does make a difference. Dispiriting as that may look, it actually is humanly and socially important. There will be a lot of victims of all kinds. I risked a lifetime in prison 40 years ago, and certainly I would do that again today.