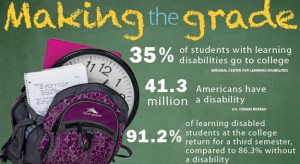

Colleges and universities are responding to a nationwide increase in students enrolled with learning disabilities by providing more services to help them succeed.

According to the National Center for Learning Disabilities, 35 percent of students with learning disabilities attend a university, up from 15 percent in 1987. At Ithaca College, Leslie Schettino, director of the Office of Student Disability Services, said the number of students using SDS has increased by more than 100 students over the past five years.

Schettino attributes this national trend to the increased sophistication of diagnoses and improved services in public schools.

“Maybe 10 years ago students were reluctant to use these services,” she said. “Now, I don’t think they are. The stigma that once existed doesn’t exist anymore and confidentiality is protected — so I don’t think most students are reluctant anymore.”

Sophomore Cameron De Tota was diagnosed with Right Brain Processing Disorder in fifth grade. Signs of this nonverbal learning disorder include an inability to read faces or body language, reduced mathematical skills and trouble developing habits easily.

“Walking down the street, you wouldn’t know that faces in my memory blur into an indistinct shape or the fact that my motor skills are so poor that I drop plates while eating,” De Tota said. “You wouldn’t know that to look at me, but it’s stuff that affects every aspect of my life.”

Traevena Byrd, associate counsel and director of Equal Opportunity Compliance, said under state and federal law the college must provide disabled students with reasonable accommodations to ensure they receive equal opportunities as other students at the college.

“It’s not at all about giving anyone a leg up,” Byrd said. “It’s really about creating balance so individuals with physical, psychological and learning impairments have the same access to resources.”

Some reasonable accommodations include assistive listening devices, textbooks on CD and permission to tape-record classes.

De Tota is allowed to use a laptop in every class because his fine motor skills are so poor he cannot write with a pencil.

“If I didn’t have the organizational capabilities of my computer available to me all the time, there’s no way I’d be succeeding,” De Tota said.

Linda Uhll, assistant director of SDS, said De Tota is just one of 570 students at the college – or nearly 10 percent of the student body – who use SDS to access accommodations for classes, exams and other academic needs. Uhll said the number of registered students rose from 442 students in 2005.

Byrd said the office can accommodate any student with an impairment or illness that affects a “major life activity.” The office also helps students with learning, developmental and physical disabilities, among other impairments.

Sophomore Samantha Sheldon frequently misses class because she has diabetes. She said she was initially reluctant to use disability services because peers in high school often misunderstood the severity of her illness.

“I’ve been asked if people can catch my diabetes,” Sheldon said. “Are you kidding me? You just want to be looked at like everyone else, but you’re different, so embrace it.”

Despite difficulties and perceived limitations, students using SDS have a higher retention rate than other students. Uhll said the third-semester retention rate for SDS students is 91.2 percent. According to the college’s data from 2010, 86.3 percent of all students return for sophomore year.

A common service is exam accommodation. In 2009, the office provided accommodations for 1,045 tests during one semester for students needing extra time or the use of a computer.

Junior Alyana Pomerantz said she uses the testing isolation rooms SDS offers because with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, it can be difficult to take an exam in a large room.

“I can’t take a test in a room with more than three people — I can’t concentrate,” Pomerantz said. “If I didn’t have those rooms, my grades would be much, much lower.”

Students first work with SDS to submit the necessary paperwork and medical information to document their disability. From there, students are paired with an SDS counselor and meet with them at least once per semester to decide what services the student needs based on their classes.

Byrd said professors are expected to grant any reasonable request for accommodation.

Schettino said most professors are willing to accommodate students, but when there is an issue, SDS advocates for the student and works with the professor to find a solution that addresses the student’s needs and does not disrupt the class.

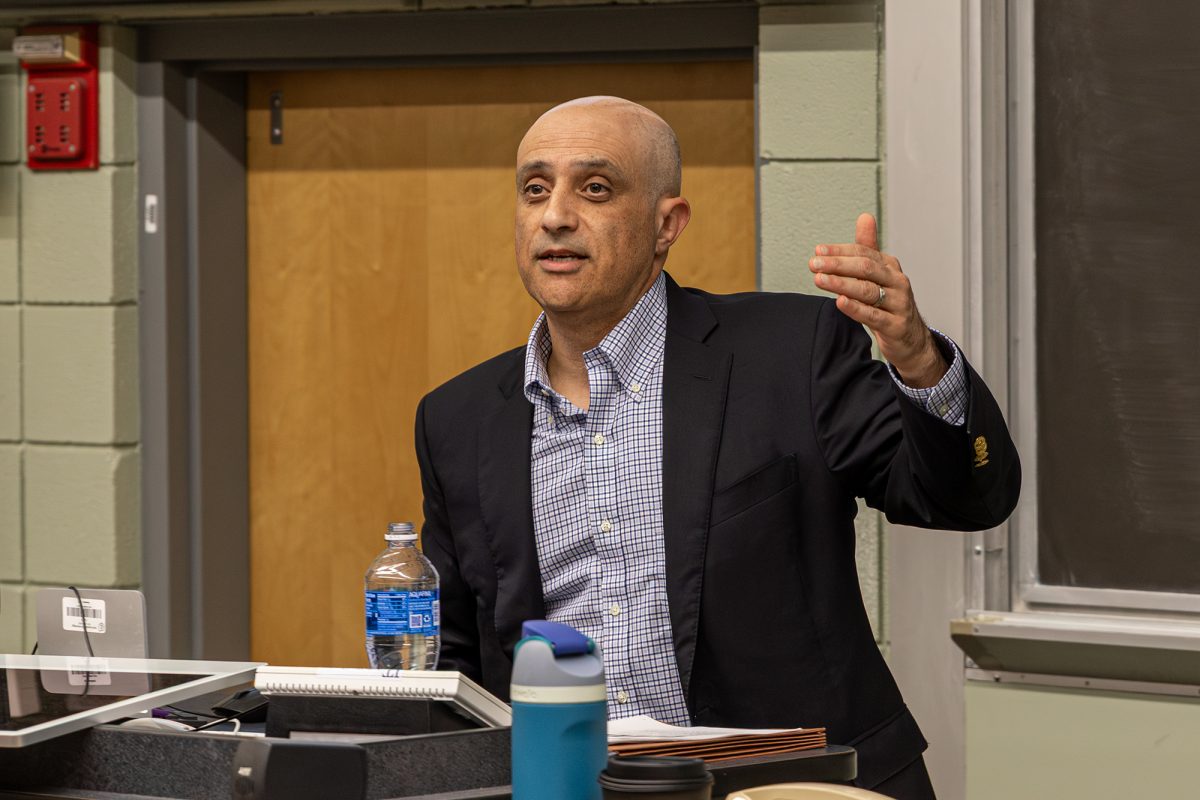

In one class last semester, Tom Bohn, lecturer in television-radio, wore a microphone and made sure to face forward at all times so a hearing impaired student could read his lips.

“SDS does a remarkable job,” Bohn said. “Each student receives individual attention, and the staff goes out of their way to work with faculty to make sure student’s needs are accommodated.”

The office contacts students’ professors at the beginning of each semester to inform them of the student’s disability. De Tota said, however, it can be best to speak with professors in person.

“I’ve found that professors are more considerate of your disability if you come up and talk to them at the beginning of the semester,” De Tota said. “It helps attach a human face to a set of papers.”

Other students also help SDS accommodate students with learning disabilities. Sophomore Hayley Nickerson took notes for a learning disabled student last spring. Nickerson said she enjoyed helping another student while also forcing herself to pay closer attention in class.

“I couldn’t imagine having a learning disability and having someone else take notes for me, so I felt like if I could take the best notes for him and for myself, that could be my way to help out,” Nickerson said. “I would definitely do it again.”

Though the college doesn’t promote their disability services in admissions materials, Pomerantz said she spent a great deal of time researching disability services at prospective universities.

“Ithaca was one of the only schools that had a good name and reputation along with good support services,” she said.

De Tota said without the services at SDS he would not be able to complete his course work or do well in college.

“I’d fail — no doubt about it,” De Tota said. “I cannot write. I have no ability to hold a pencil. It’s a not a question of ‘Just try harder, and you’ll get it’ — it’s biological. [SDS] really levels the playing field.”