Mounting frustration surrounding the Internet piracy debate has pushed controversial legislation to the forefront of campus discourse.

The Stop Online Piracy and Protect IP Acts, which were introduced last year, are now stuck in limbo in light of what some have called the most widespread Internet protest in history.

The bills target foreign infringement violators in an attempt to control online piracy and would give the government power to censor foreign sites it deemed illegal.

Ithaca College students responded to the bill and the demonstrations from popular sites like Reddit and Tumblr with a wave of micro protests on social media websites like Facebook and Twitter. Profile pictures were replaced with all-black icons or anti-SOPA images and statuses conveyed mounting discontent over the legislation.

Junior Jamie Ocheske changed her profile picture to a photo “censored by PIPA/SOPA” to raise awareness about the bills.

“I completely support everything everyone on the Internet has done because they are basically saying, ‘Look, this is what can happen if these bills pass,’” she said.

Senior Bryant Francis said the bills’ language was vague and could impede student creativity by limiting file and image sharing, and possibly removing most user-generated content.

“College students are more than just pirates — and we are not all pirates, thank you very much,” he said. “We are creators and we participate, many of us in all kinds of different activities. We share videos, we post something that we think is funny. The more artistic minds make parodies or tribute works to works of fiction.”

David Maley, associate director of media relations at Ithaca College, said the college has not taken any position on the issue and does not plan to discuss it in the future.

“The college does not generally take institutional positions in issues that are not strictly related to higher education,” he said. “And while this may have some impact on our students, our alumni and members of the college community, this is not strictly a higher education issue.”

Some college and university websites did take a stand in the anti-SOPA/PIPA movement, however. The School of Information Studies at Syracuse University’s webpage and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology admissions blog joined the international blackout to support the movement and raise awareness about the bills on campus.

On Jan. 18, Syracuse University School of Information Studies blackened its site and dedicated it to information about SOPA.

Isaac Budman, graduate student and blogger at Syracuse University for the School of Information Studies, said the bills could hinder college recruiting efforts by dismissing the Internet as a marketing tool.

“If students are doing things noteworthy that could or should be put on the webpage that have any kind of copyright overlap to anything ever, that again makes it harder to use that as an active recruiting tool,” he said.

Under the legislation, the way many colleges link to student or alumni work and achievements on college websites could be eliminated because it poses a liability threat for the institutions.

More than 100 websites, including Wikipedia and Reddit, took down portions or all of their websites, while Google demonstrated its support of the online protests by “blacking out” its header, which redirected users to a site that urged the public to sign a petition against the bill. Wikipedia’s blackout page had 162 million viewers, and Google collected more than 7 million signatures for

its petition.

On its website, Google posted an opposition letter sent to Congress signed by 110 professors across the nation. The document said the acts clashed with the constitutional right to due process because rather than waiting before the website is judged for infringement, they demand Internet service providers stop recognizing the website either by removing it or not hyperlinking to it.

The letter also argues that the limits foisted by the government on Internet service providers could “hamper the Internet’s operations and effectiveness” because of the ever-growing list of black-listed websites they have to filter

and block.

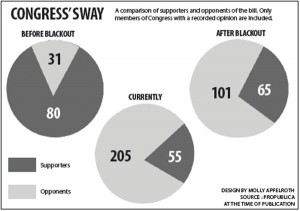

Before the blackout, President Barack Obama issued a response to the online petitions protesting the two bills.

“While we believe that online piracy by foreign websites is a serious problem that requires a serious legislative response, we will not support legislation that reduces freedom of expression, increases cybersecurity risk, or undermines the dynamic, innovative global Internet,” he wrote.

Michael Carrier, professor at Rutgers School of Law and one of the professors who signed the letter, said though the bills are now simply floating around in both Houses, this does not mean they are dead.

“In the very short term, nothing openly will happen,” he said. “My guess is that copyright owners will try to come back with another version of it that they hope will be more successful.”

While things heat up nationally, the anti-SOPA/PIPA crowd is turning its attention to the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, which was signed last October by eight nations including the U.S., Japan and Australia.

The agreement also strengthens copyright infringement penalties, but critics claim it fails to point out key exceptions by harming access to medicine and inhibiting online innovation.

The U.S. government calls it a “groundbreaking initiative” to combat global “proliferation of commercial scale counterfeiting and piracy.”

As the blackout gained momentum, a federal indictment accused Megaupload, one of the most popular file-sharing hosts, of racketeering, copyright infringement and money laundering.

The popular file-sharing website was shut down following the arrest of founder Kim Dotcom and other company officials Thursday by New Zealand police at the request of U.S. authorities. The individuals face 50 years in prison for the charges.

Carrier said many found it ironic that the Megaupload shutdown happened immediately after the blackout, but that this highlights why copyright holders believe SOPA/PIPA are needed. The new bills, he said, actually apply outside of the U.S.

“There is some authority under something called the Pro-IP Act [2008] that does give the government the power to take down these sites when there are places that can be targeted within the United States,” he said.

In the aftermath of the arrest, the “hacktivist” group Anonymous hit government and entertainment industry websites, including the Department of Justice, Universal Music and the Motion Picture Association of America.

Christopher Peterson, counselor for web communications at MIT, said institutions can play a significant role in discussing intellectual property law. Piracy is a legitimate issue, he said, but to “eliminate from space and time content and material” is an extreme measure.

“In this country, we often have debate about whether or not it is appropriate for a sixth grader to read Huck Finn, but what we don’t do is burn all the copies of Huck Finn,” he said.