For the first three months of his career, Cornell Woodson ’09 cried on his way home from work. He left Ithaca College thinking he’d be able to make a difference, but the inner-city students he hoped to inspire barely let him speak.

“I called my mom and I said, ‘Mom, I’m quitting. I can’t do this. I’m not a teacher,’” he said. “She said, ‘Get over yourself.’ It really slapped me in the face.”

After two years as a high school English teacher for Teach For America, a non-profit organization that recruits recent college graduates to teach in low-income schools, Woodson learned how to make his apathetic students care.

He joined the program to help give more students an opportunity to succeed.

“I was able to remind myself that I wasn’t there for myself,” he said. “I was there for a group of students who really needed somebody to invest in them and help them to invest in themselves.”

As the Feb. 10 application deadline for TFA approaches, students weighing in on the benefits of the program and the national discussion surrounding the achievement gap.

Hillary Wool, recruitment manager in the greater New York City area for TFA, said the organization’s mission is to work toward closing the educational inequity gap.

“Right now in America unfortunately, a child’s zip code or what their parents do for a living or the color of their skin — these factors tend to limit many children’s life opportunities,” she said.

For the first time, the college is teaming up with Cornell University to host a week of Teach For America events, including the expert panel “Race, Poverty, and the Achievement Gap: A Panel on Educational Inequity in America.”

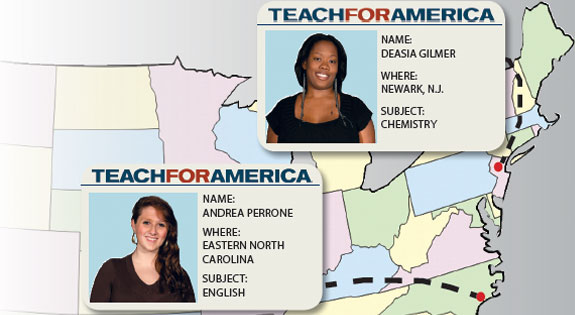

Senior DeAsia Gilmer, who has been helping to organize the panel, was in the 11 percent of applicants accepted into Teach For America this year and will teach chemistry at a high school in Newark, N.J. She said as a successful student of color, learning how poorly black and Latino students test in comparison to white students inspired her to work to close the achievement gap.

“It’s important to inspire other students of color and show them that you can have success no matter where you come from,” she said. “As long as you’re given the right resources and have those people there to help you, you can be just as successful and have high dreams and achieve those dreams.”

Senior Andrea Parrone, who will be heading to eastern North Carolina to teach English next fall, said the location wasn’t her first choice, but is excited to be a part of the program.

“It’s not going to hurt me by any means,” she said. “It’s only going to help me grow.”

According to Postsecondary Education Opportunity, an education research group, only 8 percent of children who grow up in low-income communities graduate from college by the age of 24.

In President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address last week, he said over the next 10 years nearly half of all new jobs will require schooling that goes beyond a high school education. He also said the quality of science and math education in the U.S. lags behind many other nations.

Nationally, there is a push for more people to enter the fields of science, technology, engineering and math. The U.S. Department of Labor predicts that jobs requiring science and technical training will increase by 34 percent by 2018.

Wool, who is a TFA alumna, said teachers in science and math fields are needed to advance as a nation and cultivate the next generation.

“Only about half of low-income students from kindergarten through 12th grade ever have a science teacher that majored or minored in any science or math field,” she said.

Though accepted students sign a short contract, program administrators hope that after the program, graduates will still go into fields that counter the achievement gap, Wool said.

“It’s a two-year commitment only in the fine print,” Wool said. “We want our alumni to commit their entire lives to fighting against educational injustice.”

After his contract with TFA ended, Woodson left the program with a reaffirmed desire to fight for educational justice, but through policy reform rather than a classroom. Like Woodson, thousands of college students join TFA every year and pledge two years, but most leave after their contract ends, forcing the program to fund the training of new recruits.

According to “Teach For America: A Review of the Evidence,” a study released in 2010 by Julian Heilig from the University of Texas at Austin and Su Jin Jez from California State University Sacramento, 50 percent of TFA teachers leave after their two-year contract is up and 80 percent leave after three years. This process of hiring and retraining new teachers can be costly for schools.

BRICK Avon Academy in the Greater Newark Region, one of the schools to which TFA sends student graduates, has 13 teachers and alumni from the program and two teachers in the two-year stage of the program. Dominique Lee, executive director of the school, said a school invests heavily in a teacher in the first two or three years.

“If a teacher leaves within that time frame, you have to start all over with a new teacher, so I think the argument does have some due justice,” he said. “It might be more expensive to have a Teach For America teacher just for the fact of the long cost ahead.”

However, he said, BRICK Avon Academy has a high rate of teachers staying within the district.

In a 2005 study, “How changes in entry requirements alter the teacher workforce and affect student achievement,” more than 3,700 new teachers were examined who were teaching grades four through eight. The study compared students of new teachers who graduated from teacher education programs and students of new TFA recruits. It showed that students of the recruits scored significantly lower in reading and language arts, but about the same in mathematics.

However, senior Morgan Goldstein, a campus coordinator for TFA, said recruits who do not necessarily have three or five years of pedagogical training may add to the classroom experience because they can “think outside the box.”

“It’s not about the teacher, not about the corps member, it’s not even necessarily about the one child,” she said. “It’s about the big picture and how you are working to end — one year at a time, one month at a time — this huge social problem.”

Accent Editor Shea O’Meara contributed to this report.