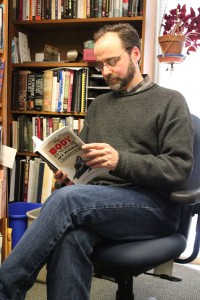

Michael Trotti, associate professor of history at Ithaca College, has spent the majority of his professional career researching murder. Now, he is reconstructing the way historians view lynchings in the South.

Trotti recently published “The Scaffold’s Revival: Race and Public Execution in the South,” an exploration of the relationship between public execution and lynching in the post-Civil War South, in the Journal of Social History.

Trotti studied 1,300 instances of public executions in the South and focused on how newspapers portrayed them and how these events unfolded during that time period. In the half-century after the Civil War, three-quarters of those legally executed in the South were

African-Americans, and more than 2,600 people were publicly executed in the South 50 years after the Civil War, he said.

“The world that I inherited as a southerner myself growing up in the ’60s and ’70s was built generations before,” Trotti said. “[I am] looking at the origins of racism in the south, at the southern way of life that was really changing as I was growing up.”

Before researching about public executions in the South, Trotti, like many of his colleagues, said he assumed that lynching and public execution in this period of history were very much alike.

“[It’s] another nasty example of destroying a black criminal’s body in public in front of a white crowd,” he said.

But he found something different than what he expected, he said. His research suggests African-Americans used public execution as a platform to show the white community that there is a higher power — a God who has control over their lives, more so than the white’s dominion on earth. This religious connotation made the white community realize that public execution was being used as a medium for protest and rebellion against their superiority and power, he said.

“Public executions were events in which the crowd celebrate the confession, the pronouncement of the condemned criminal, that he has seen his erroneous ways and he’s going to go to heaven — that the lowest among us can still be saved,” he said.

Peter Stearns, editor of The Journal of Social

History, worked with Trotti and reviewed his work. He said historians study issues of race in American history, but there is also literature on changes in public punishments and what it reflects about wider cultural shifts.

“This article contributed in both areas,” he said. “It had an unusually rich analytical payoff and very original assessments of key issues in the recent American past,” he said.

Michael Smith, associate professor of history at the college, was part of the peer review group that gave Trotti feedback on his book throughout his writing process.

He said Trotti’s book is a path-breaking study in an area of history that has not been a popular topic for scholarly research. Trotti’s imaginative new way of thinking about these subjects will get him credit for opening the doors to more research on public execution, lynching and capital punishment, he said.

“I respect how he truly is a scholar teacher,” Smith said. “He has a very imaginative research agenda.”

Trotti said he has taken a different route than traditional scholars have with this topic.

“We need to have a more sophisticated understanding of what is going on when the state legally executes someone,” he said. “This is more or less adding something new to our scholarship understanding of punishment.”