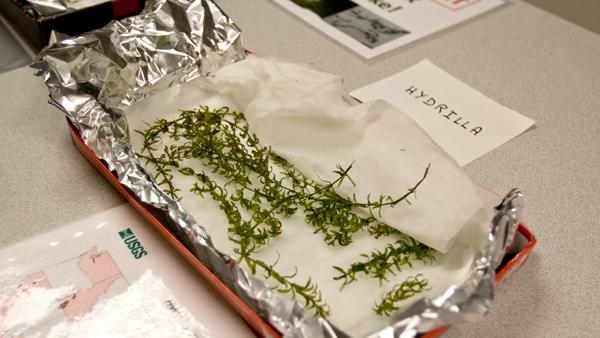

Efforts continue to identify and eradicate hydrilla, an invasive aquatic plant species in the Cayuga Inlet.

Since the first sighting last August, the Hydrilla Task Force of the Cayuga Lake Watershed, an alliance of local individuals and organizations, has worked to stop the progress of hydrilla in the Ithaca area.

Roxy Johnston, watershed coordinator for the City of Ithaca, said it is unknown how this particular strain of hydrilla ended up in the inlet.

“The biotype we have here is from around Korea,” Johnston said. “The best guess is that it was brought here from the Potomac region, because that’s the closest outbreak of this biotype.”

This strain of hydrilla has appeared in many lakes and rivers in the northern United States, according to Bill Foster, program director for Cayuga Lake Floating Classroom. The invasive species can be spread to new lakes by the means of boats and other water recreation.

The water of the Cayuga Inlet has been regularly treated with low doses of herbicides since its first appearance. Two rounds were administered this summer. In July, the inlet was closed for a day so that endothall herbicides could be administered by boat into the water. This had to be done in a particular pattern.

“We’re very pleased that [the July effort] knocked back the hydrilla very significantly,” Sharon Anderson, environment program leader for Cornell Cooperative Extension of Tompkins County, said.

Members of the Hydrilla Task Force knew that not all of the invasive tubers would have sprouted by mid-summer. A second treatment began in August using low levels of fluridone herbicides.

“As soon as the hydrilla sprouts from the tubers that were dormant, the fluridone knocks it back,” Anderson said. “But other aquatic plants are pretty healthy, so it is fairly selective, which was what we were hoping for with this low dose.”

In the past year, results have been promising. Hydrilla has previously been successfully eradicated from non-native ecosystems including Clear Lake in California and Pipe and Lucerne Lakes in Washington.

For worst-case scenarios, however, there is currently no rapid response program in place in case of a sudden, overwhelming invasion, Johnston said.

During the treatments, boats and a few divers looked for hydrilla in the inlet and lake. Johnston said almost 1,400 points on the south end and both shores of the lake were surveyed.

“The treatment seems to be very effective,” Johnston said. “They didn’t find any hydrilla growing out in the lake proper.”

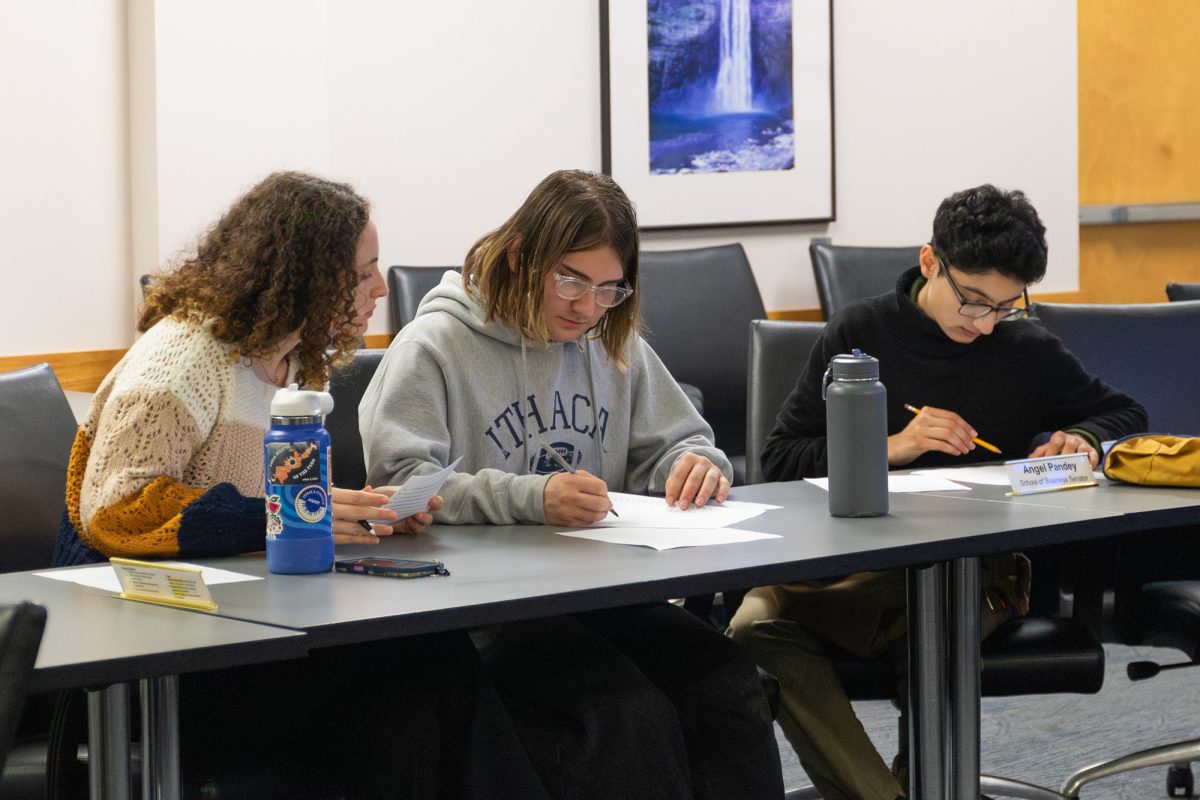

Volunteer monitors from the community joined in after being trained by the Cayuga Floating Classroom.

“We ended up doing about 110 of them with volunteers,” Foster said. “So we generated data and trained volunteers simultaneously.”

Government agencies are taking action to support ecosystem protection. A New York law passed in July — which will go into effect in January 2013 — will give the Department of Environmental Conservation and the Department of Agriculture and Markets the authority to regulate the movement of invasive species and punish those who knowingly endanger ecosystems.

Tompkins County passed Local Law No. 4 to “prevent the spread of invasive aquatic species in Tompkins County.” This law empowers local environmental authorities until the state law goes into effect.

“There’s now a mechanism to say to people, ‘Look, not only is this the right thing to do, but it’s the legal thing to do,’” Anderson said.

“Most of the funding is coming from the state and federal sources,” Johnston said. “But the in-kind agencies and governments have contributed easily well over $100,000 this year, and that will just continue on with staff support and other types of costs.”

The City of Ithaca has received at least $800,000 for hydrilla education from the New York state government this year.

Efforts such as the Floating Classroom’s volunteer education and Cornell Cooperative Extension of Tompkins County’s extensive website are in place to inform residents and visitors.

Anderson urges everyone to look out for non-native plants or animals on their boats or trailers.

“We very much need people to pay attention,” Anderson said. “We can’t be everywhere.”

Anyone who finds a possible infestation of hydrilla is asked to contact environmental authorities. The plant has bunches of 4 to 8 small, lance-shaped leaves.