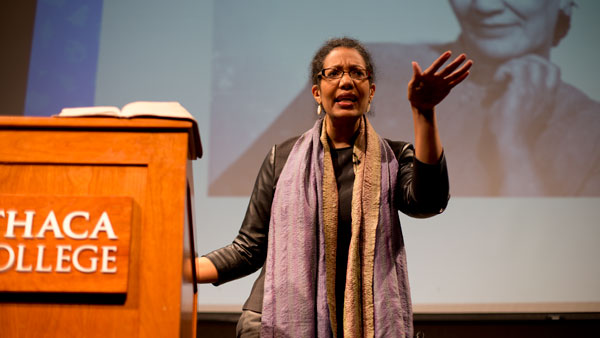

Lisa Sharon Harper challenged her audience in Emerson Suites to imagine a world where children don’t have to worry about school shootings or where their next meal will come from; where everyone goes to the doctor regularly for check-ups and people don’t lock their doors. Then she said to imagine that every person in that world is African-American.

Harper is the senior mobilizing director for Sojourners, a national, Christian-oriented organization which calls for action for social and racial justice. During her March 3 lecture in Emerson Suites, she said the imaginative task is difficult for some people because many lack the imagination to think of a world where race-based poverty is not a constant war.

The Ithaca College Protestant Community hosted Harper from March 2–3. At the Sonrise protestant church service March 2 in Muller Chapel, Harper used biblical scripture to address issues of peace and poverty to a small congregation. In Emerson Suites the following evening, the discussion broadened to a lecture-style format in a talk called “The Budget and Your Neighbor,” which drew a crowd consisting of students, faculty and Ithaca residents.

Her stop at the college is part of her “Uncommon Tour,” Sojourners’ nine-month race and poverty initiative.

ICPC Chaplain James Touchton said he first heard Harper speak at a Jubilee conference in Pittsburgh last spring and decided in November 2013 to invite her to the college.

Harper’s presentation drew on numerical data on poverty rates and the national budget to compel reactions from the audience. She traced poverty statistics among racial groups through three key eras in American History: Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, Richard Nixon’s War on Drugs and the Clinton presidency.

“Race and poverty in the United States have been intricately linked for a long time,” she said. “You really can’t talk about one without talking about the other.”

In 1959, prior to the War on Poverty in 1964, which initiated such programs as Food Stamps and Medicare, the black poverty rate — the proportion of the black population under the poverty line — stood at 55 percent, while the white poverty rate was 18 percent.

“If any group is experiencing 55 percent of poverty in our society, we have got to start asking some serious questions,” Harper said.

After Johnson’s declaration of the War on Poverty, the black poverty rate dropped 25 percent and arrived at nearly half the previous rate. The white population saw a similar effect, dropping to 9 percent by 1974.

These percentages upturned with the War on Drugs, rising to 35 percent of blacks and 12 percent of whites impoverished by 1983. Harper said this war on drugs was, in reality, a war on black communities. She said it targeted black men and increased police presence in black neighborhoods, which led to mass incarceration of a black population that was disproportionate to the demographic makeup of those committing the crimes.

Todd Schack, assistant professor of journalism who has studied and written about the War on Drugs, said he agrees with Harper’s analysis, and that Nixon’s War on Drugs created laws that were designed to prosecute certain classes and races more than others, which can be seen in historical patterns of America’s prison population.

“It’s not specifically only a war on blacks, but it’s a de facto war on people of color for sure,” he said.

By 2000, after President Bill Clinton put money back into the poverty programs, Harper said, the black poverty rate reached its lowest point in American history, 22 percent. The white poverty rate also reached a low of 7 percent. Harper said these decreases are evidence that fiscally prioritizing poverty is beneficial to everyone.

“When America has focused on poverty, everyone has benefited, and when America has taken its eyes off that ball, everyone has suffered,” Harper said.

Taking financial data from the Congressional Budget Office, Harper presented information that revealed that only 2 percent of the GDP comprises spending on poverty programs.

“Our national budget is a moral document,” she said. “It tells us who we care about and what we care about and who we care for.”

She said the country’s current challenges are to extend benefits for the long-term unemployed, reinstate earned income tax credit and raise the minimum wage.

In March 2013, Congress introduced the Fair Minimum Wage Act, which would increase the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 by 2015 in three increments and include a resolution to continue adjusting the minimum wage according to inflation from 2016 on, according to the Congressional Record.

During the Q-and-A portion after the lecture, junior Jarvis Lu asked Harper what final thoughts the student generation should be left with so the issue does not leave its mind.

“We all are college students, we go back to our lives and our homes and lose sight of things,” he said.

In reply, another audience member said whites will be the minority in the U.S. by about 2030.

Harper then said around that time, the current college generation will be in power, including leadership positions that guide the future of the country.

“You have to acknowledge the power that you have,” she said.