New data shows women who graduate from college will probably see a smaller starting paycheck than their male peers.

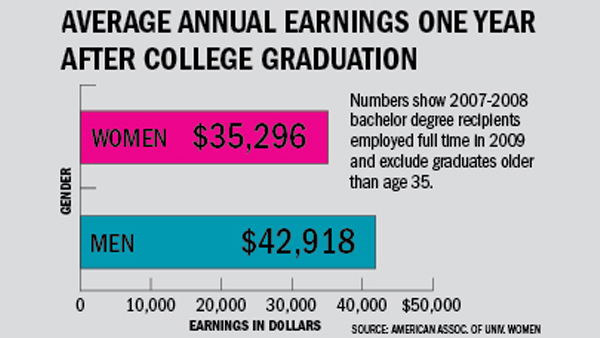

A study by the American Association of University Women published in October found that college-educated women working full time make an average of 82 percent of their male counterparts’ salaries just one year after graduation.

The report, titled “Graduating to a Pay Gap,” examined the salaries of working men and women one year out of college in 2009, when the most recent data was available, and found recent female graduates across majors and occupations made less than male graduates after one year in the workforce.

The organization, which includes former president Ithaca College Peggy Williams as a director-at-large, ranked New York sixth in the country for sex-based salary discrepancy, where the median salary for female college graduates aged 25 or older is $57,000 compared to $73,000 for college-educated male New Yorkers.

Christianne Corbett, senior researcher at the AAUW, said the organization used federal data from the Department of Education to study pay according to gender and chose recent college graduates because there should be no reason for a difference in their pay.

“We wanted to look as much as possible at apples to apples,” Corbett said. “Working one year out of college, most men and women at that stage in their life do not have kids. They’re as equal as they can be in terms of experience and family responsibilities.”

The AAUW attributed the gap to several explained causes, including occupational and major choice, as men are more likely to enter higher-paying fields such as engineering and computer sciences, while women are more likely to work in lower-paying fields such as education and healthcare.

However, the study found a pay discrepancy for many economic sectors even when looking at men and women in the same field. For example, among business majors, females made about $8,000 less than males after the first year, $45,000 for men compared to $37,000 for women. Fields with no significant difference in pay included education, healthcare and the humanities.

Though the study set controls for explained factors, including hours worked, job, economic sector and chosen study, Corbett said the AAUW found there was still a difference in pay that could not be accounted for.

“We do a regression analysis where we consider everything like major, job and hours worked, put them all together and find there’s still a 6.6 percent unexplained gap,” Corbett said.

Carla Golden, professor of psychology at Ithaca College who teaches courses such as psychology of women, said the benefit of focusing on recent college graduates working full time in explaining the pay gap is that often-cited causes, such as child rearing, part-time work and time spent outside the labor force can be rejected.

“Most economic studies of the pay gap always find some amount of variance unexplainable,” Golden said. “This study, like most studies, was able to point to certain things which explain the gap, and yet still there’s some amount of variance that’s unexplained, which people then attribute to discrimination, unconscious mostly.”

One portion of the unexplained gap, Golden said, can be attributed to women being less likely to negotiate for a larger salary than men, an idea that the AAUW study cited as possible and that is supported by Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever’s book, “Women Don’t Ask.”

“A difference of $2,000 to $3,000 in the beginning can attribute to the basis for a pay gap in the first year but can accumulate over years,” Golden said. “It turns out that even for a woman that’s been in a job for any number of years, they tend not to ask for perks or merit increases or travel money.”

There are many factors that could account for this, Golden said, including early socialization of women to reject aggressive behavior and a belief that their good work will automatically be noticed. However, Golden said, women of color are more likely to be conscious of structural obstacles like sexism and racism that are in place.

“If you’re more aware we live in a patriarchal culture where men and women are judged by different standards, you might be more aware that you’ve got to advocate for yourself,” Golden said. “For many girls, it never occurs to them that you could be worth a lot of money and that maybe you’re worth more than you’re being offered. You can see this at all levels.”

In September, a Yale University study found that when male and female scientists were given identical applications, but with male and female applicant names, the applications from females were scored lower for competence, ability to be hired, and mentoring. Both female and male scientists were also more likely to offer the female applicant a lower starting salary.

Senior Mariana Garces, vice-president of IC Feminists, said knowing about this pay discrimination makes current economic uncertainty more daunting and said the effects of gender pay gap will become more familiar after working in a salaried position.

“It is scary to think about graduating into that wage gap already, even though I’m going to be struggling to find a job,” Garces said.

Ultimately, Garces said, the pay gap can be resolved by educating people about the pay gap, mobilizing to change it and supporting legislation to address it. In June, the Paycheck Fairness Act, which would require employers to demonstrate discrepancy in pay to male and female employees was not gender-related, failed in the Senate.

“It’s important for us to see this now and start to do something about it,” Garces said. “It doesn’t have to be like this, we can change this, not only through educating women but also by educating men about the interaction and the structure we live in.”