As the United States becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, politicians are becoming increasingly concerned with “preserving,” “protecting” and “enhancing” all that is supposedly “American.”

Concerns from politicians and political candidates about the absorption and incorporation of our nation’s newcomers, though chiefly those from Latin America, continue to center on the supposed perils a Latino majority would inflict upon the nation. This fear inspires highly questionable political maneuvers at all levels of government.

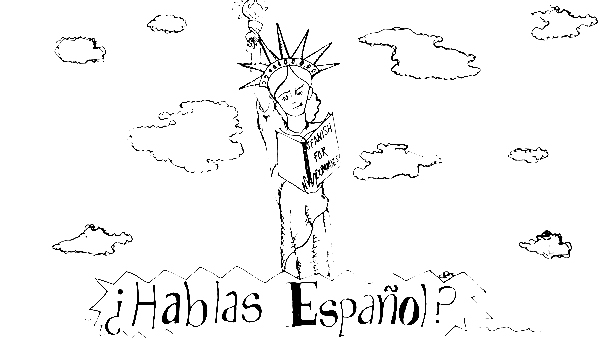

The prophesied threats of “foreign” languages (mainly Spanish), ushered in by growing levels of immigration, continue to justify and legitimize efforts to “protect” the English language and the American way of life from those who represent a threat to our stable community. Campaigns galvanized around English-only legislation continue to gain momentum, particularly at the state level, where GOP officeholders and candidates insist that efforts toward national unity are stifled by “divisive” language accommodations that, in reality, hamper our attempts at unity.

Contrary to popular belief, at no point in American history has the United States had a national language. Despite legislative attempts in both chambers of Congress to pass measures making English the national language, to date, all have failed. Prior Supreme Court decisions and congressional actions like Puerto Rican Organization for Political Action v. Kusper in 1973, Lau v. Nichols in 1974, the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 and Asian American Business Group v. City of Pomona in 1989, to name only a few, established a correlation between language discrimination and racial and national origin discrimination that we continue to see today.

This paranoid style of American politics, historically rooted in the socio-political experiences of many immigrant groups and communities of color, continues to exist by means of discursive political formations steeped in anxiety, suspicion and polarity. Examples of such political paranoia are omnipresent, including a 2012 episode involving Alejandrina Cabrera, former city council candidate in the southern Arizona border city of San Luis.

Cabrera was labeled “not sufficiently fluent” in English by the Yuma County Arizona Court and removed from the ballot in accordance with the state’s 1910 Enabling Act that requires both office holders and political candidates to “read, write, speak and understand English sufficiently well,” At face value, this law may seem acceptable — even self-explanatory — however, that could not be any further from reality. This 18th-century law does not specify or quantify proficiency, nor does it articulate ways to measure fluency, providing enough legal elasticity to deny the absorption and incorporation of Cabrera and other groups of people whom lawmakers deem undesirable.

The decision to remove Cabrera’s name from the ballot,w even upon appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court, leaves many unanswered questions and further directs suspicion toward a state legislature engulfed in a political crisis over both its initial enactment of Senate Bill 1070 along with its banning of Ethnic Studies classes in public schools.

Many English-only initiatives are based on fear, distrust and suspicion. With glaring omissions of evidence from proponents, this paranoid style of American politics continues to corrupt our collective consciousness on immigrants, immigration and those perceived as “foreign.” Political attempts to paint certain demographic groups as impediments toward societal progression and social order must be understood in the context they are presented — devoid of fact.

Donathan Brown is an assistant professor in the department of communications studies. Email him at [email protected].