The year was 1863. President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which promised to free enslaved African-Americans and pave their path for citizenship.

Flash forward 100 years to August 28, 1963. More than 250,000 gathered to march in

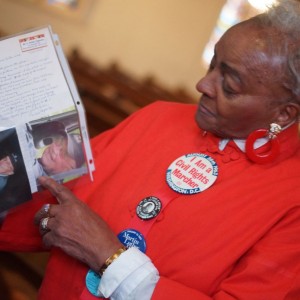

Courtesy of Erin Irby

the largest demonstration for freedom, justice and equality ever seen in the District of Columbia.

Now, fifty years later, a group of Ithaca College students went to tell the untold stories of individuals who participated in The March on Washington.

Over Easter weekend, associate journalism professor James Rada and 12 Park Scholars drove down to the capital armed with tripods, dSLRs and Canon cameras. We began our own media march and, along the way, we captured the narratives of local residents who participated in the 1963 March to Lincoln Memorial for the main event. These interviews will be part of Rada’s documentary to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of The March on Washington.

In high school, many of us learned about the civil rights era as a black people’s movement — one separate from the concurrent labor movement, LGBT movement, Native American movement and feminist movement. We were shown clips from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech and told that it politically activated African-Americans to stand up for their rights and bring an end to oppressive Jim Crow laws.

But we were not told that The March on Washington was also a wake-up call for the rest of America — predominantly the affluent white sectors — to join their black brothers and sisters in the century-long fight to end injustice nationwide.

To help fill in the gaps missing from our history books, we interviewed people Rada made connections with during his time living in D.C. and working at Howard University, a historically black college. A pair of sisters came from Baltimore to march on behalf of their youth group, fathers went to the mall to inspire their children, and activists were reignited that day to keep fighting for justice and equality. These extraordinary narratives came from ordinary citizens who had yet to publicly share memories of their march in an exercise of true democracy, one that was largely fueled by younger a generation.

Most recently, we saw this same youth fervor in the Occupy movement for economic justice for people of all racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. It showed an organic solidarity we had not seen since the 1963 March. Yet here we are, two years later, engaged in a political struggle for LGBT rights and immigration reform.

Our trip to D.C. illustrated the civic service of media to give back to the community, but it also hinted at some of its dangers. Today’s technologies have an incredible ability to create disparate communities that transcend borders, yet our relationships with people and local communities are growing less and less personal. Our weekend spent visiting museums, debating about racial politics over meals and hours of endless conversation proved that there’s something to be said about communing, community and communication. Most of society has gotten away from that.

While few of the interviewees knew one another when we brought them together for this project, they were all part of the same movement 50 years ago, politically activated by a call for justice, freedom, jobs and equality. These same sentiments are very much alive today, but we’re too distracted and too separated to collectively act on them. At its core, this project illuminated the strength of intergenerational movements, and the critical need for the dialogue they open between all of us.

Megan Devlin is a junior Park Scholar and the incoming editor in chief of The Ithacan. Email her at [email protected].