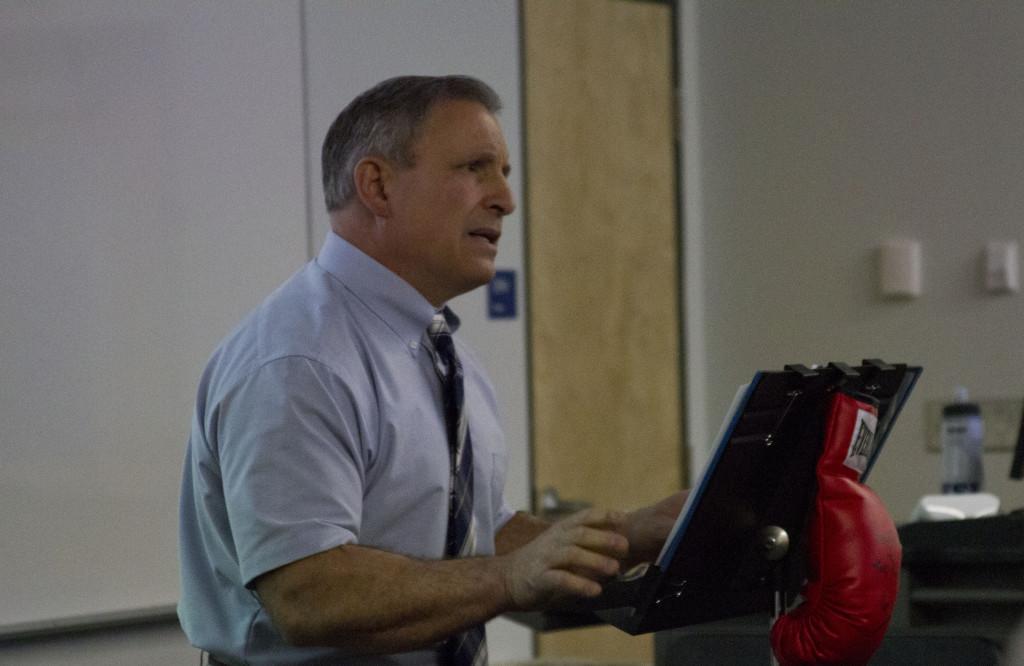

A retired boxer whose career was derailed 40 years ago by multiple head injuries spoke April 3 at Ithaca College about head trauma in sports and the risk athletes take by re-entering their respective sports before they are fully healed.

Ray Ciancaglini has dealt with recurring headaches, a common symptom of concussions, since 1969 when a boxing match in Buffalo, N.Y., left him dazed from a strong right hook to the back of the head.

A 2011 study by the National Institutes of Health found the annual incidence of sports-related concussions is estimated at 1.7 million in the United States. The same concussion report found that the rate of concussion has been increasing steadily over the past two decades, a statistic it attributes to better concussion detection technology and more concussive impacts.

But when Ciancaglini was boxing in the 60s, concussions were not as well understood. After Ciancaglini’s head-injury during his fight in Buffalo, the boxer began training in preparation for another match at the Syracuse War Memorial. Ciancaglini said the week of training following his injury was the first time he confronted the headaches he encountered and addressed his concern about the concussion symptoms to his training staff.

He said his training staff replied to his concerns about the recurring headaches by telling him it comes with the territory of competing as a boxer.

“My future problems could have been avoided if I had not ignored the concussions symptoms,” Ciancaglini said.

According to the NIH, a concussion is a short loss of normal brain function in response to a head injury. Some common symptoms of concussions that athletes should look out for include headaches, dizziness, nausea or lack of coordination. But concussion symptoms may be felt days or weeks after the accident.

Ciancaglini, determined to prove to his colleagues he was ready to be credited as an “elite boxer,” returned to the boxing ring one week after Buffalo with lingering concussion symptoms. But, during this fight in Syracuse, N.Y., Ciancaglini was struck by his opponent with a heavy punch that left him with another concussion. Ciancaglini said he remembers being disoriented at the end of the fight.

“I had not even known that I lost until an interview with a sports reporter after the fight,” Ciancaglini said.

The boxing match in Syracuse left him with a second concussion in under a week. A group of doctors conducting research on brain injuries diagnosed him with “dementia puglistica,” a type of head trauma caused by repeated concussive and subconcussive blows.

Ciancaglini fought through the pain from the head trauma for several years by self-medicating with aspirin in order to continue competing in professional boxing.

Trainers continued to tell the boxer the headaches would go away, but they did not. Ciancaglini said he retired, as a result, in 1974.

“I reluctantly threw away my gloves and all my memories when I realized that the headaches would not go away,” he said.

When he retired from boxing at the age of 20, as a result of concussions, Ciancaglini returned to complete high school and then attempted to attend college to become a gym teacher. However, he said he could not retain information properly with his injured brain, which forced him to withdraw from college. Today, the boxer lives with Parkinson’s disease, insomnia and dementia.

Relating Ciancaglini’s experience to those of student-athletes, Chris Hummel, clinical associate professor and concussion researcher, said when athletes at the college return to play after a concussion, it’s a day-by-day process.

“Anybody who is suspected of a concussion or showing any symptoms of a concussion is not allowed to return to the field until they are cleared by the medical staff,” Hummel said.

Hummel explains returning to the field involves three steps: Athletes must be symptom-free for at least 24 hours, and then they must complete a cardiac stress test, which involves working out on a cardio machine for five to 10 minutes to raise one’s heart rate and ensure that concussion symptoms do not return. The next day, the athletes then run with their teams at practice. After one more day, they practice with the team but sit out for exercises that involve contact with other players. When student-athletes successfully progress through these steps, they are then cleared for full practice, Hummel said.

Junior Ben Tillem, an active EMT certified by the state of New York, said he encounters athletes of certain sports more than others when responding to concussions.

“The most common athletes I witness being transported to the hospital with concussions are football players and cheerleaders,” Tillem said.

Today, Ciancaglini advises all athletes to undertake proper examination by a health professional after a head injury, no matter what the circumstance. Ciancaglini said any athlete debating coming back from a head injury to compete should wait until they are fully healed.

“The game you sit out today could be the career you save tomorrow,” Ciancaglini said.