On Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, people vouch “never again” will the atrocities of the Holocaust occur. However, Jewish Holocaust survivor Samuel Rind said the phrase does not retain meaning if genocides have continued to happen both before and after the Holocaust.

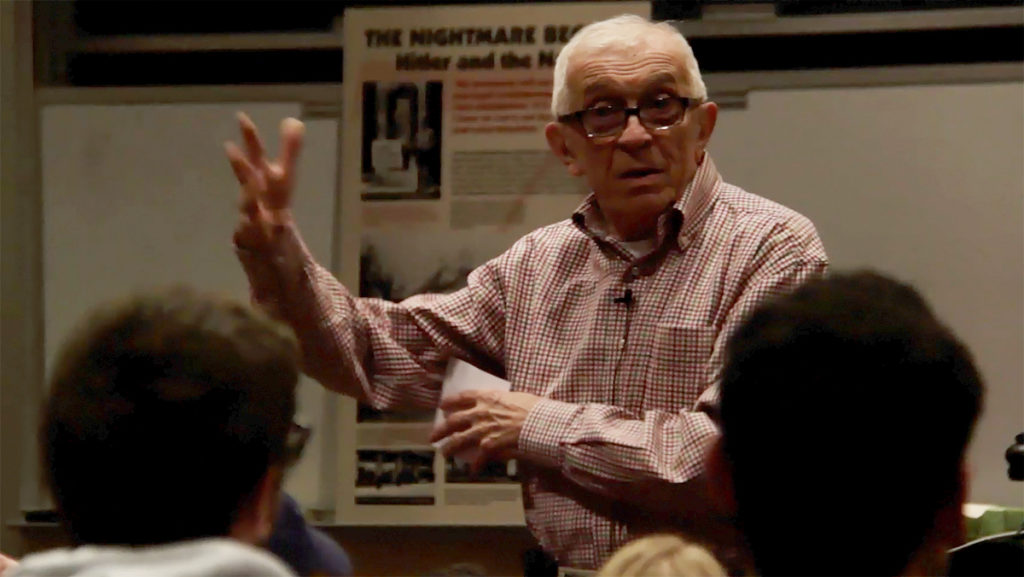

Rind spoke to approximately 50 students, faculty and community members in Textor 102 on April 24. He said it is painful for him that many people are unaware or unmoved by the events in history that lead to and aided in the murder of 20 million people, approximately six million of which were Jews. Referencing genocides occurring in places such as Syria, he said affirming that saying “never again” does not equate to paving ways to prevent and stop genocide in its tracks.

“Time and again these tragedies happen, and we forget,” Rind said. “It hurts me, it really hurts me, when a junior in high school doesn’t know when Hitler was elected to power, and it’s not the fault of the teachers.”

The event was hosted by Hillel at Ithaca College and organized by Sarah Krieger, vice president of engagement for Hillel, as part of the event series for the week of April 23 for Yom Hashoah.

Rind was born in Krasnobród, Poland, and his family split up into groups once the Nazis invaded Poland, despite the fact that many Jews thought it was wiser to stick together. Of his group, consisting of his mother, father, younger brother, aunt and her three children, the only survivors were him and his mother. Months after fleeing Poland they were caught by guards on the Eastern front and were sent to a labor camp that became a death camp, Pechora, in Vinnitsa, Ukraine, formerly Poland. Here he saw his aunt and three cousins shot and murdered by camp guards.

Another problem Rind’s family faced was food scarcity. Rind’s father brought valuables, such as gold, with him, and traded it with locals in the towns surrounding the camps to buy food.

Many credit locals for harboring and helping Jews and other persecuted peoples during the Holocaust, but Rind said this statement angers him because their silence aided in the suffering and genocide Jews and others faced.

“They say a lot survived because of the help,” Rind said. “How would you like to turn in an 18-karat gold ring for a f—ing potato? That’s what they did. They helped.”

His younger brother would eat the meat of the potato, Rind would eat the skin and his parents split the broth, but this small amount of food was what kept him and his family alive, he said.

“They gave us what horses, pigs and cows didn’t want to eat,” Rind said. “But to us, it felt like a banquet. When you’re starving, when you are half of what you should be weighing, everything tastes like a banquet.”

Now when Rind sees people throwing away and leaving food on their plates at restaurants, he said it physically pains him.

“I close my eyes and feel like crying,” Rind said. “I feel like screaming.”

Eventually, when his father did not return from trading gold with locals for food, the family presumed that he was dead. Shortly after, Rind and his mother had to watch as guards beat his little brother in the head with a stick until he was dead. Shedding tears, he said this was the hardest death of all.

Jewish partisans, who his extended family was connected to, helped him and his mother escape by dressing him up as a girl and sending them to the bordering country of Ukraine.

In Ukraine, his family saw a Ukrainian male wearing his father’s custom jacket, and his mother’s brother, in a crime of passion, shot the man. Rind said that the Eastern Europeans often were more anti-Semitic and brutal than Germans.

“The worst Nazis were not German,” he said. “It was the Romanians, the Ukrainians and the Albanians. The German guards had some compassion and sympathy.”

He said he saw German guards get shot by Nazis on the spot after they refused to carry out orders.

Once in Ukraine, Rind and his mother lived with a wealthy Jewish-Ukrainian, and when Rind was liberated in March 1944, his family attempted to flee as refugees to the United States but were turned away twice because of United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Jewish immigration quota. This quota only permitted a certain number of Jewish refugees into the U.S., and as a result, many Jews who fled to the U.S. before and during the war were sent back to Europe and most likely killed. Because of this, Rind and his mother fled to Bolivia, one of the few countries that accepted Jewish refugees.

Most famously, in 1939, the St. Louis Manifest brought German-Jewish refugees to the U.S. to seek sanctuary, but the U.S. government sent them back to Germany. The majority of these Jews were murdered in death camps. The ship originally went to Cuba, but the Cuban government also turned them away.

“I saw more death in six months than most of you will see in your lifetime,” Rind said. “How did the world allow all that stuff? Why didn’t the United States let people in?”

He said if United States President FDR’s policies were different, he could have saved another 150,000 Jews. The U.S. also learned about the camps in spring of 1944, over a year before most of the camps were liberated, and could have bombed the railroad tracks to Auschwitz-Birkenau, he said.

Prior to 1939, the U.S. was one of eight countries to accept Jewish refugees. The U.S. accepted 95,000 refugees, which was the most out of the eight countries. Additionally, 60,000 refugees fled to Palestine under the British Mandate, 40,000 fled to Great Britain, 75,000 to Central and South America and 18,000 fled to Shanghai, which was occupied by Japan at the time, according to the United States Holocaust Museum Memorial.

Krieger said she was happy that Rind could share his story, as it is important to educate both Jews and non-Jews.

“It’s really important to have this conversation with non-Jews who have never met a Holocaust survivor,” she said.

The Holocaust and World War II were subjects freshman Alexandra Zanni was interested to learn about in high school, so she said she was excited to hear Rind make the subject more tangible.

“You hear about this stuff in school, but you don’t really hear about it from people who experienced it,” Zanni said.

Rind said he acknowledges that many people are not able to process such horrific events, which is why he enjoys telling his story to people in both small and large groups. He said that despite how difficult it still is to talk about, he shares his story to raise awareness and encourage people to act when injustice is occurring. Being educated and aware about the events that led up to and took place during the Holocaust is not enough, he said.

“Please, we can do a lot,” Rind said. “There’s a lot of places we can write to. Let’s take a few minutes everyday and write notes to organizations, and send them a dollar or two. We live in a country where money is power, let’s use it the right way. Let’s not buy votes; let’s buy people.”