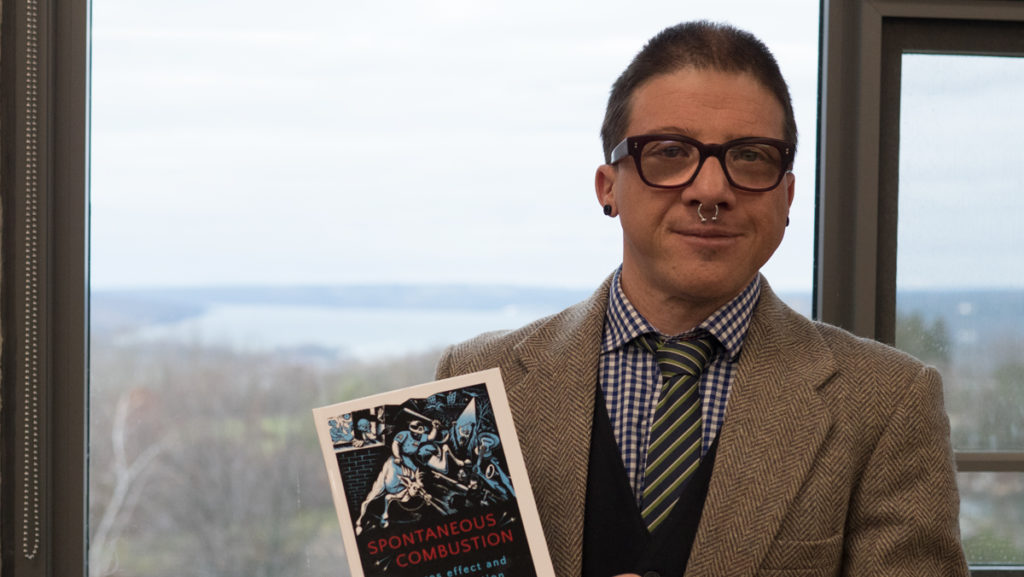

Andrew Thompson, assistant professor in the Department of Sociology, recently co-authored a book titled “Spontaneous Combustion: The Eros Effect and Global Revolution” with Temple University professor Jason Del Gandio.

The book builds on the work of George Katsiaficas, the first person to introduce the idea of “The Eros Effect.” Thompson said that the Eros Effect refers to people’s loving connections to one another and their ability to build human relationships based on solidarity and mutual aid rather than on competition and greed. The book applies this concept to clarify the spontaneous times of global social revolution in history, when large masses of people decided to take a stand against injustice and inequality.

Staff Writer Krissy Waite spoke with Thompson about his book and its importance.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Krissy Waite: How did you originally become involved with the book? Did you know your co-editor beforehand?

Andrew Thompson: Jason invited me to participate in a panel on the Eros Effect at a conference of the International Herbert Marcuse Society in 2013. Marcuse was a key figure in a lot of the social movements in the 1960s, like anti-racism and feminism. He was the teacher of Angela Davis and George Katsiaficas, who this book is centered around and who first introduced the concept of the Eros Effect. Because I had been in collaboration with George in the past, Jason contacted me as a potential contributor to the panel. After the panel, it became clear that there was a large amount of interest in this topic, as it was very relevant, especially in this moment, where we had just seen this massive wave of global rebellions. There was interest in gathering this material into a book, so Jason asked me if I would co-edit a volume with him, and I agreed.

KW: What was the importance of your specific contributions?

AT: I was one of the editors of the book; there were two of us. We edited the collection and assembled the contributors and tried to provide a shape to the book. In terms of my contributions, I helped to draft the introduction to the volume, and in the initial section of the book, we reprinted an interview I did with George Katsiaficas. In the last section, I did a rejoinder.

KW: Can you further explain your chapter “Eros Effect or Biological Hatred”?

AT: One of the claims that Katsiaficas makes when describing the Eros Effect is that it is the natural impulse toward loving connection that pushes people into political uprising and that the sense that things could be better is what motivates people. Normally, we feel undermined and thwarted by the world, and we forget about that capacity to connect to others. But every once in awhile, we’re reminded of it, and that’s what compels rebellion, from Katsiaficas’ standpoint. I argue that if you read Marcuse closely and look at what actually happens on the ground, the Eros Effect can help to connect people once they start struggling, but it is not the motivation that compels people. If you want to find that motivation, I argue that it is much more useful to focus on the experience of “lack” that we all have experienced — the experience that we feel like our lives are incomplete, that we’ve been deprived of opportunities. These can range from the most basic, like food or shelter, to being deprived of meaningful human relationships. The experiences are very different, but they amount to the same thing. I’m asking the reader to evaluate which is the precondition to social rebellion. I argue that while Eros can allow the rebellion to spread, it is not the precondition.

KW: How long have you been researching this topic, and why do you feel it so important?

AT: I think that the question of how and why protests emerge and why they take the form that they do has been a question that’s been with me since I began studying sociology and looking into questions of social inequality and justice. I believe it is important because even though there’s a tremendous amount of scholarship on this question, we often have a hard time making sense of and predicting moments of global uprising, even though we can recognize how important those moments are for social change. We don’t know a lot about why they start when they do or what it is about specific situations that allows things to ignite when other times, they don’t.

KW: Have you seen the Eros Effect take place on Ithaca College’s campus?

AT: I started working here in the Department of Sociology this fall and am just getting a sense of where things are at on campus. I think that from Katsiaficas’ perspective, the Eros Effect is often a large-scale phenomenon, but there can be indications of it in smaller settings. If we were to find evidence of it, it would be in those instances where people have come together against injustice and feel the bonds of community that arise in those moments when it becomes possible to envision that things can be different than what they currently are.

KW: How can students benefit the most from reading this book?

AT: I think the thing that I hope students take away from this book is that there are reasons to feel inspired. Often times, it can seem that nothing will ever change and that when we’re in the midst of our daily lives, it is hard to avoid feeling stuck. I think that makes sense, but that it is also important to put that experience into perspective and to recall that it is not always like this; there are moments when windows open up and we’re confronted with opportunities we never expected. We do not know when those windows will open, but we can learn to be attentive to them and to respond when we see them. I want students to be aware of this possibility, and even if it feels like it is always going to be this way, history suggests otherwise.