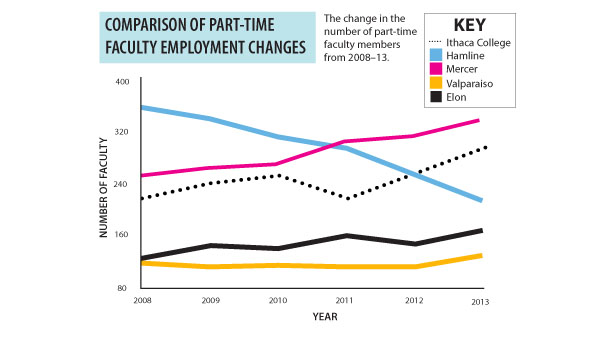

In recent decades, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of part-time, per-course faculty employed in higher education. Employment trends at Ithaca College follow in these national footsteps.

According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, from 1976 to 2011, part-time faculty numbers increased by 286 percent, while the numbers for full-time tenured or tenure-track faculty only increased by 23 percent nationally in both public and private higher education institutions. From 2004–13, the college’s number of part-time faculty increased by 67 percent, while full-time faculty only increased by 11 percent.

Diane Gayeski, dean of the Roy H. Park School of Communications, said sometimes the Park School prefers to employ part-time faculty to teach specific courses, a mentality that is a reflection of the college-wide hiring process.

“In some cases, these part-time folks are teaching other regular courses, sometimes lower level, 100 level, that kind of thing, and if there were a stable need for it, and we knew that, maybe ideally we would get eventually a full-time position,” she said. “There are other cases in which, especially in a professional school, we actually want part-time, per-course people because they teach very specific classes related to their disciplines.”

According to the college’s Faculty Handbook, a part-time, per-course faculty member is expected to have a term of fewer than three years and only take on 50 percent or less of a full-time professor’s workload, which is a maximum of 24 credits per year and also includes additional responsibilities like being an academic adviser to students and potentially conducting their own research. An adjunct has an expected term of three years or more and is responsible for 58 percent or more of the full-time workload.

Though the college distinguishes between the two, David Garcia, associate provost for business intelligence, said most of the time when people talk about adjuncts, they actually mean part-time, per-course faculty. Many people use the words interchangeably, he said.

Part-time faculty are paid on a per-credit-hour basis, and Garcia said the rate of pay at the college is currently $1,300 per credit hour. As of the 2013–14 school year, out of the 785 faculty who work at the college, almost 38 percent, or 295 people, are part-time faculty, which is up by 10 percent compared to the 175 part-time faculty who were employed in the 2004–05 academic year.

While part-time, per-course faculty and adjunct faculty are defined differently by the college, the two groups face similar problems in terms of being perceived as second-class faculty, and the instability of their employment could lead to concerns for students seeking a close-knit college experience.

Karen Rodriguez, assistant editor and production coordinator at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, worked as an adjunct assistant professor in the Park School from 2008–09 and again in 2010–13. She said she was fortunate enough to have family and a husband to depend on for health benefits and to help financially, as she only earned $8,800–$17,600 per year depending on the number of credit hours she taught. Her courseload was also easier because she was re-teaching classes for which she had already written up lesson plans. However, the lack of monetary and insurance benefits could be a problem for others, she said.

“The hourly wage was actually decent,” Rodriguez said. “But you’re capped at a certain number of credits, so you’re limited on the amount of money you can earn as an adjunct. And also, you don’t get benefits.”

Mark Coldren, associate vice president of human resources, said one of the big issues higher education is now wrestling with is whether or not the Affordable Care Act will require colleges and universities to provide part-time faculty with health benefits.

In addition to the monetary differences, Michael Smith, associate professor of history, said the increased use of adjuncts and part-time faculty on a college campus can potentially diminish the quality of faculty-student relationships on campus.

“One of the promises that is basically made to you [students] when you apply here and enroll here is that you’re going to have a lot of faculty attention,” Smith said. “And you are going to be able to come and have conversations with your professors during office hours, and they are going to be available, and that is simply impossible for adjuncts to do.”

In the wake of the increased use of part-time faculty in higher education, many of these faculty have been attempting to organize unions to advocate for more equal rights compared to full-time faculty. In 2012, Smith and the Labor Initiative Promoting Solidarity, a student organization dedicated to workers’ rights, were advocating for more rights and awareness for part-time and adjunct faculty at the college, particularly focusing on the lack of job security and health benefits and the amount of respect they receive on campus. However, the group made little headway and has since dissolved, and the publicized fight for part-time faculty rights at the college went with it.

Junior journalism major Eileen Oaks said she has taken courses taught by part-time faculty in the past, and has had both good and bad experiences with them. While she said she hasn’t kept up with adjunct unionization in the news, she said it makes sense.

“Part-time professors need to be treated with as much respect as full-time professors,” she said. “Maybe if they got the respect that they deserved, then they would have more time to dedicate to the school and to their classes, and they wouldn’t feel like a fly-by-night kind of job.”

Special Projects Manager Elma Gonzalez contributed reporting to this article.