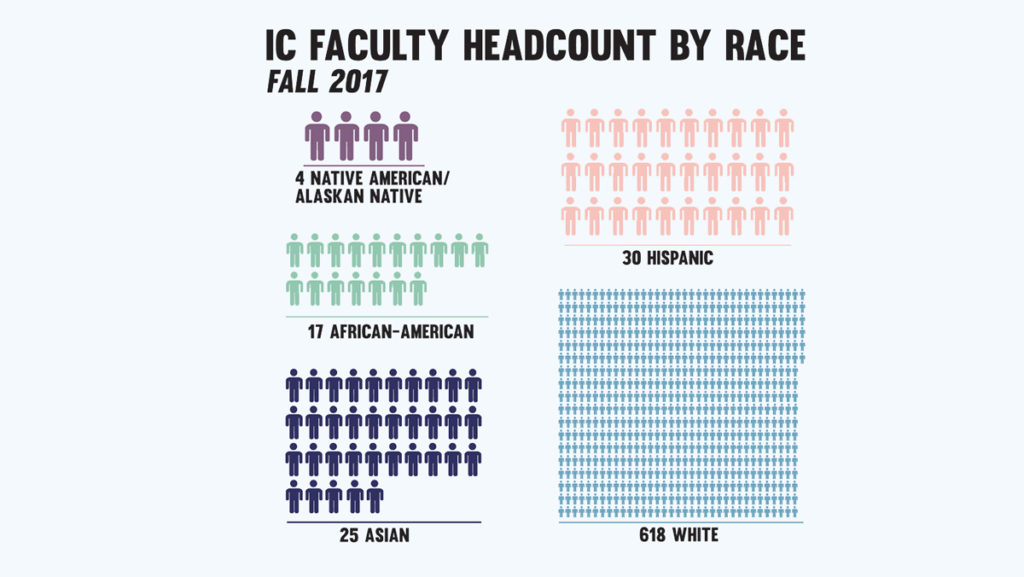

With only 11 percent of faculty at Ithaca College identifying as African, Latino, Asian or Native American, the college has identified issues in the hiring process and launched new initiatives which include outreach and better–trained search committees to identify biases.

The college is a predominately white institution with 72.9 percent of its students and 84.4 percent of its faculty identifying as white. There are only 17 African–Americans, 25 Asians and 30 Hispanics out of the 732 faculty that work on campus.

One of the initial problems the college has in trying to recruit faculty of color is broadening where departments post job search ads and how they are communicating the position, said Donathan Brown, associate professor and director of humanities and sciences faculty diversity and development. Brown is working on finding ways to communicate ads differently to reach a wider audience in job searches. Instead of relying heavily on outlets such as The Chronicle of Higher Education to post job descriptions, Brown said in an email that the college should look at other academic, graduate student and minority–serving organizations that could provide the college with greater exposure.

Brown and his team are also conducting audits to find out why faculty of color leave the college and engaging in small focus groups with faculty of color in an effort to find out what their needs and wants are.

Brown said there are multiple reasons why faculty of color are not staying at the college, including the feeling of lacking institutional support.

“That’s the million–dollar question,” Brown said. “I see it as a series of issues. One, for any group of individuals having a strong cohort that already exists is helpful … Two, institutional culture and climate.”

Aside from working on the way that the college reaches wider audiences, Brian Dickens, vice president of human resources, is partnering with Cornell University and the Tompkins County Chamber of Commerce to create a Recruit to Ithaca campaign in an effort to better advertise to academics and the social and professional opportunities in Ithaca. This campaign includes trying to recruit people who grew up in Ithaca to come back and work here, but also trying to recruit people from diverse populations.

Dickens said he believes that it is hard to recruit minority faculty to the Ithaca region. Faculty may not want to stay in Ithaca because they don’t feel supported or they feel their needs aren’t met within the community, Dickens said.

The college recently started a new initiative to better train the search committees that hire faculty across the campus. Danette Johnson, vice provost for academic programs, was part of this committee alongside Belisa Gonzalez, director of the Center for the Study of Culture, Race and Ethnicity and Michelle Rios-Dominguez, associate director of Provost and Educational Affairs.

“We developed a set of training and development activities for faculty focused on biases in the hiring process and how to address issues of bias throughout various parts of the hiring process,” Johnson said.

Johnson is also tasked with reviewing finalists and semifinalists in faculty searches to make sure diversity is appropriately taken into account by the search committee, and that there are no candidates that appear to be comparable with candidates who moved forward that have been excluded based on race.

Dickens said the committee also provides a guide for all of their search committees that addresses these issues titled, “Searching for Excellence & Diversity: A Guide for Search Committees.”

In the guide, there are six essential elements of a successful search, including how to actively recruit an excellent and diverse pool of applicants, raise awareness of unconscious assumptions and their influence on the evaluation of applicants, and how to ensure a fair and thorough review of applicants.

These sections give the committees examples of common social assumptions and how to minimize bias in the search process. They are hoping that this training will help improve the diversity of candidates that get called back for interviews and ultimately hired, Dickens said.

Hamline University, an institution in the college’s peer group of similar institutions as defined by The Chronicle of Higher Education, also has 11 percent of its faculty identifying as ALANA. Hamline has 333 faculty members, whereas the college has 732. Loyola University New Orleans, another school in the peer group, has 14 percent of their faculty identifying as ALANA out of 437 faculty.

One way that the college recruits potential faculty is through the Dissertation Diversity Fellowship Program, also known as the Diversity Scholar Program, that was started by the School of Humanities and Sciences during the 2010–11 academic year. This program hires scholars that are in their final year of writing their dissertation or who have just completed their dissertation and supports them in their research for the academic year . These scholars teach one course per semester. Out of the 26 full-time diversity scholars that have been a part of this program over the years, nine have been hired on as full-time faculty once the fellowship was over.

For this academic year, four diversity scholar fellowships were written into the budget, two in the School of Humanities and Sciences and two in the Roy H. Park School of Communications. The funds for this program come out of the Office of the Provost. H&S hired two full-time scholars, one in writing and one in women’s and gender studies.

The hope with this program is that the diversity scholars will be hired as faculty members to the specific departments they work in after the year is up Carla Golden, professor and women’s and gender studies coordinator, said. She said she believes that the program is not big enough and that there should be more scholars in the program. Golden believes that expanding this program will help with recruitment of faculty of color in the long run.

Diane Gayeski, dean of the Park School, said the money the Park School was given to hire these scholars was not enough to bring on two full-time scholars for the year. Instead, the Park School used the funding to bring in three emerging diversity scholars or artists for one-week periods.

The goal of this type of program is to give these individuals experience in teaching and exposure to the college in hopes that they will apply here, Gayeski said.

Elizabeth Wijaya was the first emerging diversity scholar and artist that came to the Park School in mid-November, with the next scholar, Peta Long, coming in late February and another, Nate Rodriquez, coming in late March.

Shehnaz Haqqani, a diversity fellow in the Women’s and Gender Studies Department, said she has really enjoyed being a part of the program and has felt supported in her research for her dissertation. Haqqani said she has been able to attend conferences and form a weekly writing group with three other faculty of color thanks to the support of the Center for Faculty Excellence. The Center for Faculty Excellence has also provided her with funding for editors to work on her publications, she said.

“I truly feel like I’ve thrived here so much,” Haqqani said. “I’m very very happy and I’ve experienced this very genuine effort to keep me as satisfied and my needs as satisfied as possible,” Haqqani said.

Haqqani stressed that it would be beneficial to have a stronger cohort of fellows in the program and that the college would benefit from adding more money to the budget for this program.

Getting faculty in the door is only half of the battle. The college also must create a safe, welcoming and supportive atmosphere for faculty of color to ensure that they stay here. Johnson, along with Gonzalez; Wade Pickren, director of the Center for Faculty Excellence; and Roger Richardson, associate provost for Diversity, Inclusion and Engagement, worked together on a retention committee to address the needs of the pre-tenured faculty of color at the college. Johnson said that mentoring and support for scholarly work are the two biggest areas that need to be focused on based on feedback.

Johnson said that the retention committee is working to make faculty more aware of mini-grants that are available through the provost’s office that provide financial support for scholarly work. She also said the faculty-in-residence program at the college, which consists of faculty working on a program of study related to faculty excellence and development, is focusing on developing mentor plans for faculty of color.

At the human resources level, Dickens is also helping to create an inclusive space for the ALANA faculty.

“We’ve created ALANA coffee hours,” Dickens said. “We created opportunities for our faculty and staff to come together and just sort of have an affinity group or resource group available on IC’s campus … There tends to be a greater retention strategy around engaged employees.”

Dickens said the ALANA faculty hold diversity circles every Wednesday during the noon hour to discuss different current events where people feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and connecting each other with resources.

Cynthia Henderson, associate professor in the Department of Theatre Arts, has participated in a few of the ALANA faculty meetings, as well as other faculty luncheons and talk circles when she can.

“I find it nice to get out and connect with the other ALANA faculty and staff on campus,” Henderson said. “It’s helpful.”

In 2007, Henderson became the first African–American female to be tenured in the history of the college.

“I think it was a little more difficult for me because there are aspects of my background, my upbringing, who I am as a woman of color, that were not understood or taken into account … not because necessarily a mean–spirited nature, but not understanding or not taking the time to find out who I am as a cultural being,” Henderson said.

Henderson said her cultural differences factored into her having a difficult time going through the tenure process.

Aside from the tenure process, Henderson said, because the college is such a white institution, it has been harder for her to feel supported in some aspects of her career. Henderson also said there have been moments of sincere support from her colleagues during her time at the college.

Audrey Williams June, a senior reporter for The Chronicle of Higher Education, writes about recruitment and retention of faculty members in higher education. She said she has found in her research that it is difficult for faculty to go through the tenure process without a mentor.

June said that colleges and universities can do a better job of making their guidelines more clear and creating an environment that faculty of color feel supported and comfortable to go up for tenure in.

“I think making sure that there’s things that universities could do to make sure that the environment is one in which minority and other people of color feel like they are able to pursue the scholarship that they want to pursue and still have it count … for tenure and promotion,” June said.

The number of students of color seeking out faculty of color for mentoring and advising is another issue that presents itself with so few faculty of color on this campus. Only 2.3 percent of the college’s faculty identify as African–American. The ratio of African–American students to African–American faculty on the college’s campus is 22:1, compared to an 8:1 ratio for white students to white faculty.

Junior Alyse Harris said that students of color specifically seek out faculty of color.

“Students are looking for resources on campus and people to relate to, and because the pool is so small, it really ends up pulling these professors to be stretched really thin, and they get burnt out in the same way students get burnt out,” Harris said.

Freshman Isabella Pillay said that it is important for students of color to have professors of color and fears that some students will never get that opportunity on this campus.

“Seeing them represented in front of them in the classroom really does help, so I definitely do think it’s a problem, especially for students of color who will never have a professor of color,” Pillay said.