Oftentimes, music is perceived as a field that takes years of preparation and experience to study at the collegiate or professional level. However, this can lead to a divide between students with musical and nonmusical backgrounds when participating in the same music-related course.

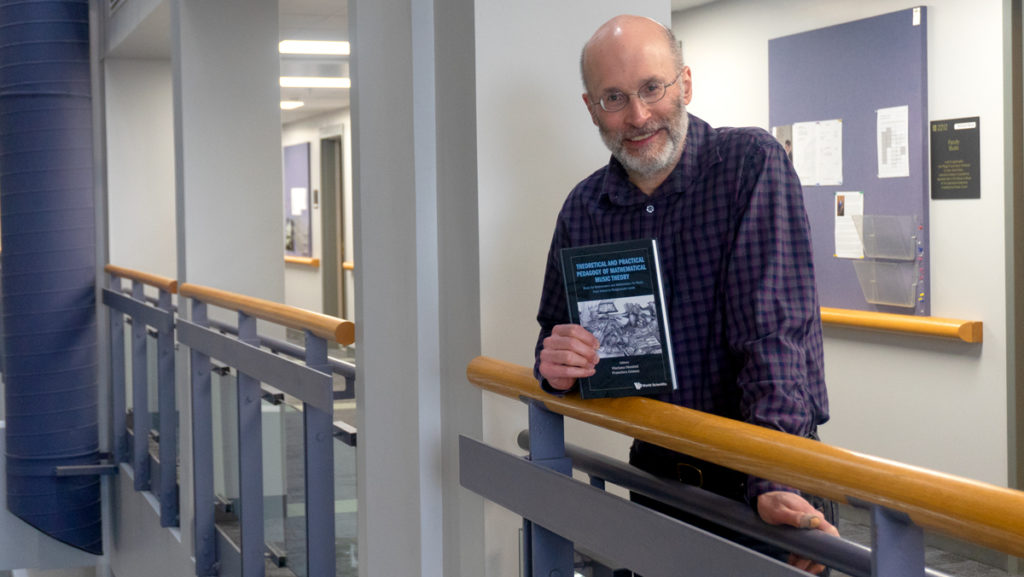

Timothy Johnson, professor and chair of the Department of Music Theory at Ithaca College, History and Composition, recently published a book chapter on the pedagogy of teaching students with both musical and nonmusical backgrounds with mathematical music theory. Mathematical music theory allows for components of music, like notation, rhythm and meter, to be related to numerical measurements of time and distance. The chapter is titled “Creating a Level Playing Field for Non-Music Majors,” and is a part of the book “Theoretical and Practical Pedagogy of Mathematical Music Theory: Music for Mathematics and Mathematics for Music, From School to Postgraduate Levels.”

Opinion Editor Meredith Burke spoke with Johnson about his decision to write the chapter, how he hopes it will benefit music theory classes and his upcoming projects in music theory.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Meredith Burke: For our readers, could you give a brief overview of the chapter?

Timothy Johnson: I have a book that’s intended for both [music] majors and nonmajors that deals with mathematical music theory, and what I found is that, … if you have a class with mixed amounts of experience in music — which you very often do when you have a population like that — that the playing field is completely unlevel. So you call it leveling the playing field. … What I wanted to do was have [the chapter] be a little nonmusic, entry-level friendly. … So instead of talking about notes and intervals and the sort of jargon that goes with music theory so much, we get more quickly to numbers standing in for notes, which allows students to be able to make the calculations they need to do without that second level of abstraction. … What I’ve tried to do is produce a method that would be transferable to populations of different backgrounds in a class — make the transfer easier for them.

MB: Why do you think “leveling the playing field” and making music more accessible is important?

TJ: In this case, the work that I’m doing is fairly abstract to begin with. So when you’re teaching it to nonmajors, they can do it, but it can be frustrating if you don’t have any musical background. When I’ve taught this to nonmajors — let’s say they’re all nonmajors in a class, some of them played an instrument in high school, some of them played the guitar and maybe some of them still do. Some of them sing — they all have different music backgrounds. Some of them never touched an instrument and don’t know a C from a D. So with all those different backgrounds, it can get frustrating for everyone, in a sense, because the ones who already know the notes don’t want to take the time for the teacher to explain to everybody how the notes work. And the ones who have no idea, you can’t not tell them how it works. You can’t teach a course within a course so you can get those who don’t have the background up to the level of the other ones that do, and yet, it would be possible to teach the things I’m trying to teach to all of them at the same time. Somehow, you have to get over the barrier of the notation and the familiarity with music.

MB: Why did you decide to write the chapter?

TJ: I guess because of having taught nonmajors and … noticing this problem and trying to find ways to solve it. When I’ve taught nonmajors with this course, it’s been an Ithaca seminar. … Just going through that experience, you learn for the experience of doing it what are the problems and how I can fix that kind of thing.

MB: What do you hope this chapter will accomplish?

TJ: I hope that it will allow for an opportunity for teachers to better reach students of varying backgrounds in a course like that.

MB: Any final thoughts?

TJ: One of the things I really like to study is how music relates to other fields. I like teaching that way, thinking that way. … A lot of my work looks at music in a broader context that includes history, baseball, math, social and cultural issues and many things like that.