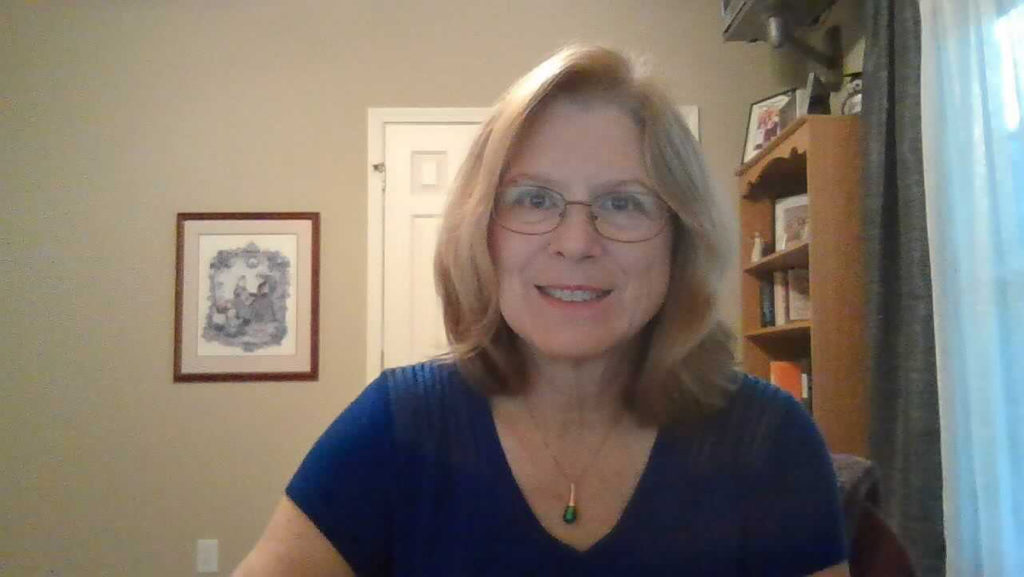

Asma Barlas, professor in the Department of Politics at Ithaca College, went on a U.K. tour this summer to promote a new edition of her book titled “‘Believing Women’ In Islam: Unreading Patriarchial Interpretations of the Qur’an.” The book was originally released in 2002.

Opinion Editor Brontë Cook spoke with Barlas about her identity as a “Muslimah,” her U.K. book tour and the way interpretations of the Quran have changed in the last 20 years.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Brontë Cook: What is your book about?

Asma Barlas: The book is about trying to read the Quran, which is Islamic scripture, as an

anti-patriarchal text. … Historically, Muslims have interpreted it as privileging males — and it can certainly be read as doing so. But, … the kinds of meanings we produce from texts have a lot to do with how we approach them. … One of the points I make is that, although I don’t think women and men necessarily read texts differently in every instance, I do believe they bring different kinds of experiences and different kinds of questions into the reading. … I made an argument as to how the Quran’s differential treatment of women and men with respect to some issues is not in and of itself a sign of inequality. It’s a sign of difference — and difference is not always inequality. …My point is that if there is a God who is beyond sex and gender, and the Quran is the word of God, why would this God be falling prey to a petty sexual partisanship and saying, “I really prefer men, I want to privilege men?” There is no theological or ontological reason for the Quran to privilege men. … So this book was published in 2002. Since then, Margot Badran — she’s a feminist historian — has included it in the genre of Islamic feminism.

BC: How do you feel about being referred to as one of the “mothers” of Islamic feminism by Islamic feminists and feminist historians like Badran?

AB: It’s not a name I chose for myself. I’ve had three public debates with Badran about why I resist her naming me that. My question to Badran has always been, … “As a historian, you know that feminism is a fairly recent phenomenon — why are you trying to read it back into time?” … The language I use about patriarchy is very feminist … but I still resist that naming. … I, as a believer, like to believe a Quranic word for myself and that’s enough for me. The Quranic word is Muslimah — “a believing woman.” So that’s why my book is called “Believing Women.” … I come from an ex-colonized country, and one of the things colonized people are denied is the right to name themselves and their experiences. So I absolutely insist on naming myself — I mean you’re welcome to call me what you want — but that’s why. There was also that personal element — I don’t want you to be naming me and slotting me into this and that category.

BC: Why did you go on an international book tour 20 years after the book was originally published?

AB: When I sat down to write about patriarchy, no one was calling the Quran anti-patriarchal. Today, some Islamic feminists say the task is to unread patriarchy from the Quran, which is the subtitle of my book. … The book created its own literature. So I revised it, I added a new chapter to it and I responded to some of the critics who have emerged in these last 20 years — feminists, Muslim feminists who are secularly inclined. They believe women like me are just trying to prop up the authority of the Quran.

BC: Why did you tour the U.K., specifically?

AB: The book tour was organized by Saqi, a very well-known press in the U.K. [The book] was published with the University of Texas Press, and they hold the copyrights. But, for the first time, they gave the right to another press in another country. So, when Saqi did that, they invited me for the book tour. … The book has been reissued. I’ve also updated chapters over the years because I learned a great deal from feedback and critiques, and new literature came out … there’s now so much literature that wasn’t there in ’98 or ’99 when I was writing. … This second edition has suddenly grabbed people’s attention, especially in the U.K.

BC: How did the public’s response to your book differ between 2002 and 2019?

AB: The first time I presented my findings, … I was hissed at; I was booed. Young Muslim men wouldn’t let me get off the podium. They were in my face and screaming. They were so upset for me just saying simple things I thought should be obvious. This time, fully 20 years later, there’s a generation of young Muslim women who’ve grown up in those years — and it was a fundamentally different experience. … I mean, there were women who were crying when they met me because I guess my work in some ways changed their lives. There were women who just made a mad dash for me, which is not something I ever expected to happen. … I’d usually expect to get heckled. [There was] this yearning and this desire to sort of put the collective feet down about women’s rights. And interestingly, none of the young Muslim men in the audience, or the older Muslim men, said a peep. My husband was with me, he was recording all of this, and he was also stunned. … I was overwhelmed by it.