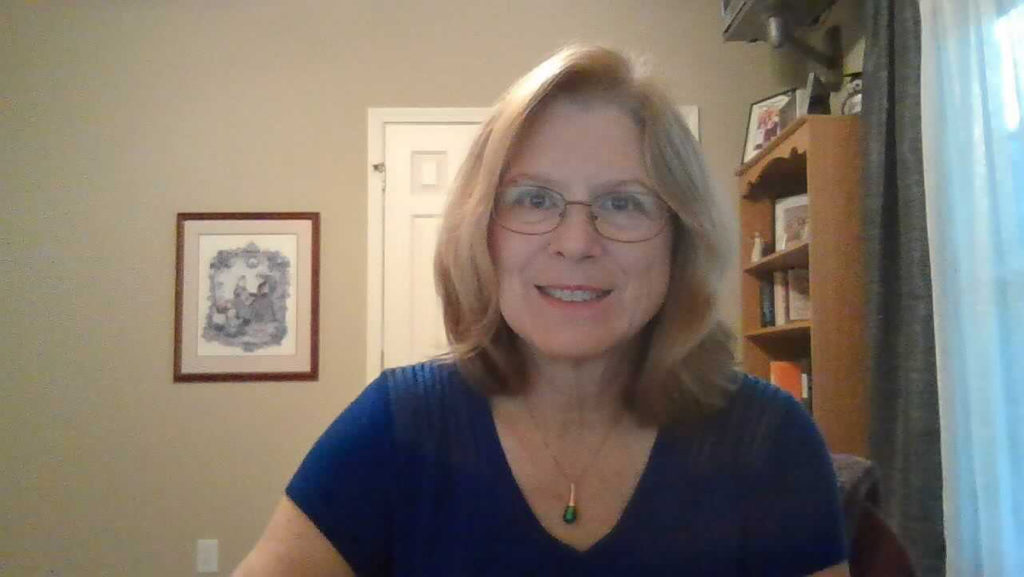

Chris Holmes, associate professor and chair of the Ithaca College Department of English, recently published a chapter in the fifth volume of The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to World Literature. His publication examines writer Kazuo Ishiguro’s experimentation with literary form and his interest in pushing the limits within genre.

The chapter is titled “Kazuo Ishiguro’s Thinking Novels” and is a culmination of his previous research and publications on the works of Kazuo Ishiguro.

Opinion editor Kate Sustick spoke with Holmes about the ways in which Ishiguro conveys a larger meaning of identity and how it inspired Holmes’ chapter.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kate Sustick: What led you to your current research?

Chris Holmes: [My recent publications] are part of a book project that I have been writing for a long time that is about the ways in which we start to see literature doing more than just being a storehouse of culture and history, which we open. And we consume that or a purely aesthetic object. … Instead, think about how books may or may not change the very ways in which we produce thinking. … These articles are both about Kazuo Ishiguro. … He, in my mind, is the epitome of a writer who wants to do more than simply represent a cultural moment and ask questions about the ways in which we produce the kind of thinking that we think of as our own and whether literature can change that production of thinking.

KS: What is the story the author is trying to tell? How is this shown in your publication?

CH: The two articles on Ishiguro each take on a different crucial idea for our moment. … The first one is an article about “Never Let Me Go,” which is a story about cloned schoolchildren in 70s, 80s and 90s Britain. … The obvious connections [are] to things like cloning and the ways in which we see that science advancing. I’m less interested in that and more interested in the broader, overarching sense that a kind of corporate mindset is behind the logic of a society that would end up doing this kind of thing to its citizens. Corporation mindset involves a limitless sense of privilege for the very few. Privilege allows for you to rationalize the idea that someone else will suffer for your greater good. Rather than see it as science fiction, I see it as a novel that wants to test “What are the limits that we have for who can count as human?” … My theory for Ishiguro is that he wants to take us to what I think of as “the limit.” The more recent article I wrote is asking questions about identity in our current moment and also class and the kinds of work that people do. It asks it through thinking about genre. [Ishiguro] is a guy who started his career writing about a kind of cross-cultural British/Japanese experience, which was both his own and not. Then, [Ishiguro] wrote this novel that many consider to be the quintessential modern English novel, “The Remains of the Day,” which is about an English butler. [Ishiguro] was Japanese by birth but is a very English, middle-class author writing about an English manor house in the mid-20th century. He carved a niche for himself as someone who writes classic British novels, … but then his most recent novels are both clearly operating with tropes of different genres.

KS: In the abstract of your chapter, you close with the following phrase: “Thinking according to the novel’s limits is in this way the beginning of meaning–making rather than the end.” Could you expand more on what you mean by this?

CH: You start to choose new ways in which you make meaning from what you read if we pick up a book and say, “I’m going to enjoy this, and I’ll also end knowing something different.” … Sometimes when students critique books, they say, “It was not relatable to me.” There’s a sense that they’re saying, “I have to already know the experience. … These experiences in culture and language and history have to be familiar to me, and I don’t really need to learn anything. And I don’t need to change the way I think.” Ishiguro, among many contemporary novelists, especially those that get read very widely across cultures, are very aware of this. … I would argue that Ishiguro is saying that people hit a limit to their understanding of something. You hit a limit to your expectations for the novel. You hit a limit to your fundamental ways of thinking about what literature does. And at that point, thinking begins. When relatability can’t happen anymore, what happens next?

KS: How do you hope to expand this area of your research?

CH: The nice thing for me, which is accidental and purposeful at the same time, is that it allows me to talk about any major issue of our time because I read mostly contemporary things in my research. The last chapter of my book is about forced diaspora, immigration and people without place thinking about how the limits that those people encounter are in many ways the most cemented and held fast of any kind of human experience. … This idea of limits is very real and no longer a kind of literary form or function. If you want to look at someone whose life is structured entirely by limits every day — where you can live, what language you can speak, what religion you can practice, how you can travel, be close to your family, not be imprisoned — these are all real and absolute limits. What you see now is a lot of contemporary writers writing about that experience, and they use the experience to both talk about the very specific political problem [of immigration] that will become more and more massive, especially as global warming causes for mass refugee communities to be moving all over the world. But also to ask, “What do these kinds of limits on what makes us human say about every kind of experience we have and the way we think about the world?”