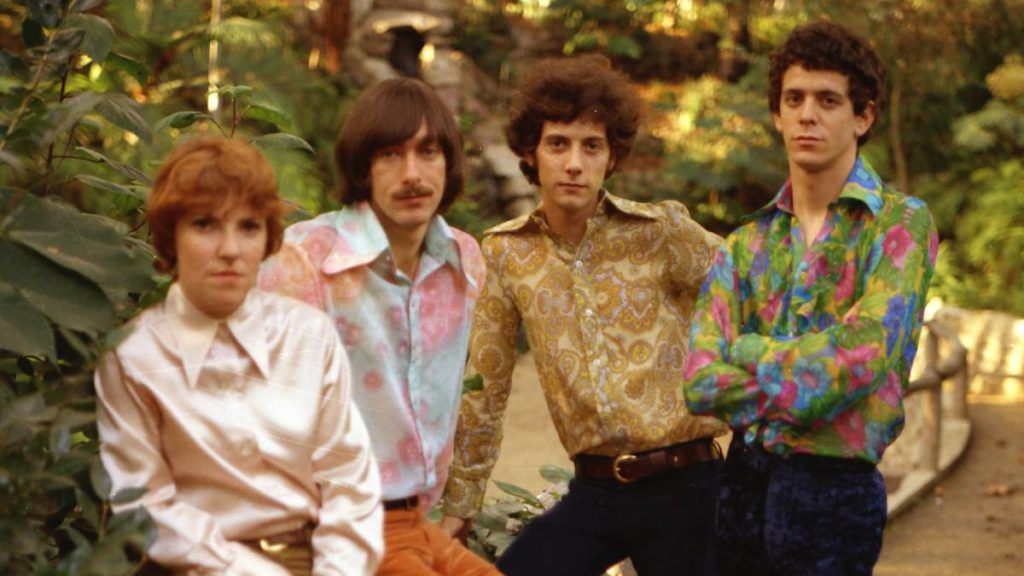

It all started when John Cale, a classically trained violist, met the rule-bending, crackly-voiced dreamer, Lou Reed. The musicians caught a whiff of the New York City 1960s avant-garde scene and never turned back. In pursuit of rockstar-level fame, the two followed their dreams to the city, where distinguished names in the art community like Andy Warhol and Nico took interest in their creative endeavors.

In the first documentary on The Velvet Underground, director Todd Haynes guides viewers through the band’s rise to stardom, the slow fizzling out of its original members and everything in between. The story, from start to finish, is told through kinetic collages of avant-garde art, jealousy-inducing photos of Warhol’s inner circle and hazy, vintage clips of performances. These marvelous cultural moments are all set to narrations and interviews of the band’s original members and other key figures in the 1960s art world.

Haynes captures not only the incredible aesthetic of this world, but its spirit too. From stills of Nico’s icy stare and clips of Reed cast in dim, nostalgic light to overwhelming time-lapses of judgemental crowds, Haynes finds intimacy in the intimidating.

By lending recognition to the group’s intelligent uniqueness, the documentary also sheds light on the musical specifics of The Velvet Underground’s never-before-heard early punk sound. Interviews with Cale assist in explaining the group’s experimental use of drone pitches, overtones and the harmonic series — techniques that aided them in revolutionizing popular music. Though importantly informative, the segments that lend themselves more to music theory nerds may be a bit too much for the casual fan.

Nearly each scene is set to the genre-bending classics that The Velvet Underground scored the avant-garde world to, pulling viewers into the exciting sensory overload that was sweaty Manhattan clubs in the late ’60s.

While the shots are extraordinarily beautiful, Haynes manages to depict the gritty reality of the era at the same time. Old news segments discussing negative views on homosexuality coupled with Reed’s dark lyrics of drug use and sexual exploitation show the other side of the often overly-romanticized ’60s. The documentary also features an interview with the film critic Amy Taubin, who explains the sexist nature of the Factory — Warhol’s former headquarters — which is an often overlooked detail in the Warhol Factory-era discussion. Taubin more than bluntly discloses that in the Factory, women were sexualized, exploited and valued for their looks rather than their talents.

For the most part, the documentary matches the pace of the fast-moving era it depicts until around the hour and a half mark. With a runtime just short of two hours, the documentary drags on a little too long. Perhaps the pacing is supposed to mimic the pace of the band’s career, but it’s unlikely. After detailing the height of their fame, the scenes begin to lull and the interviews become extensive and almost unnecessary. Cale quits, Reed fires Warhol and Nico pursues a solo career, leaving Reed, guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen Tucker to find replacements, and it’s all a slow decline to the credits after that.

However, the eventual lagging and poor pacing of the last 30 minutes does not detract from the captivating anecdotes that make up the visual and aural wonders of “The Velvet Underground.” Haynes effectively exhibits the duality of the New York City avant-garde age with regard to how people who created the culture were viewed by the outside world. The inside look that the documentary offers captures the essence of early punk rockers who were somewhere between too cool and too high to care.