Step into the Handwerker Gallery to explore moments in the history of queer and people of color sex work frozen in time alongside education on current social justice dilemmas — all underneath the vibrant glow of neon signs and the poppy rhythms of disco music.

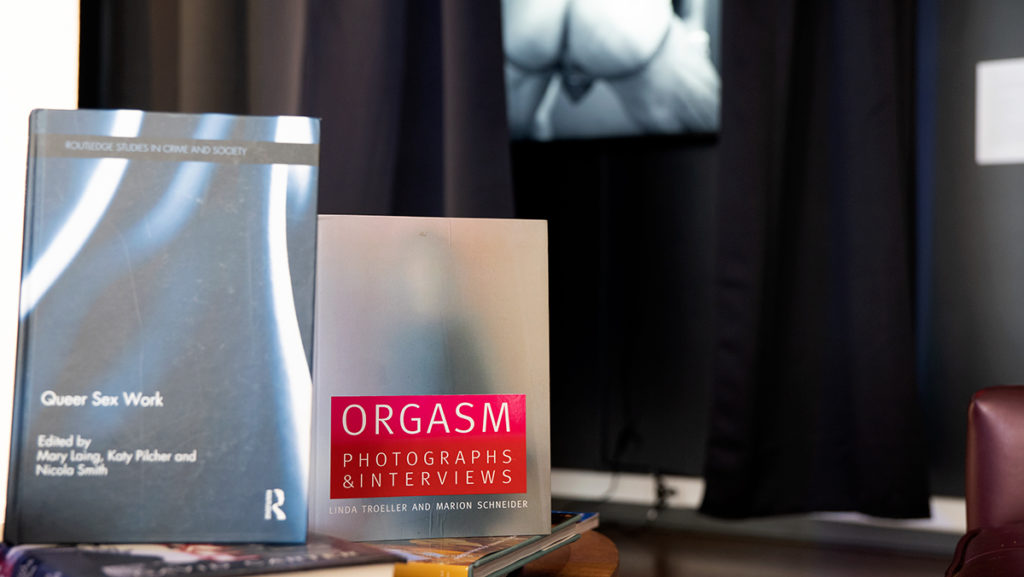

From now to March 11, the Handwerker Gallery is displaying “On Our Backs: The Revolutionary Art of Queer Sex Work,” curated by Alexis Heller. The exhibition explores first-person sex–worker narratives through a display of videos, photographs, paintings sculptures artifacts and even an interactive video game. The collection features 22 artists and was originally displayed at the Leslie Lohman Museum of Art from September 2019 to January 2020, but has since been re-curated and resized to bring to Ithaca College.

Mara Baldwin, director of the Handwerker Gallery, said the Handwerker has never hosted an exhibition of this size or on this subject before, but they thought it was a good fit for the college. They also said that because of the heavy content, the gallery worked with the college’s Office of Title IX to provide pamphlets on sexual assault education at the entrance of the gallery.

“We have a large LGBT presence and the women and gender studies program just added ‘sexuality studies’ to its name, so with that rebranded, it just seems timely,” Baldwin said. “It’s also about porn, and while we have a communications school here … there’s a line of respectability that most people have that doesn’t include sex and sexuality, certainly not queerness, which is all marginalized in that field.”

As acknowledged by the Handwerker Gallery’s website, the artworks and artifacts that make up the exhibition “offer a rich, yet incomplete portrait of LGBTQAI sex work culture.” Sex work is often misrepresented and misunderstood, especially in the media, so as a result, sex workers face stigmatization and censorship on top of the dangers that their work brings, especially within marginalized communities.

The gallery’s website says, “‘On Our Backs: The Revolutionary Art of Queer Sex Work’ honors the ongoing labor of LGBTQAI sex workers at the forefront of the fight for liberation and the ways in which art and community have helped sustain and celebrate them.”

Heller said she is most interested in curating exhibitions around marginalized queer identities because before she became a curator, she was a social worker. She said she spent over 10 years working with LGBTQ+ teenagers — many of whom were sex workers — so in curating this collection, she collaborated with and consulted sex workers to ensure she was telling an accurate story.

Heller also said she wanted to bring the collection to college campuses to educate students on histories that they may not get to hear in the classroom. She said she hopes the exhibition can inspire activism in students to not only educate on the subject’s history, but also inform on current issues that sex workers face.

“Sex workers are still really struggling to this day to get even just basic rights,” Heller said. “Particularly in law with [The Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (SESTA/FOSTA)] … which can cause a lot of online sex workers to lose their platforms. … And so, I also think that it’s an exciting opportunity to engage students in activism that’s happening now and to create allies, and the way to create allies is to connect them with people and history.”

The 2018 SESTA/FOSTA bill was created in attempt to shut down websites that facilitate sex trafficking, but as the sex-work-world has migrated into the digital realm, it has had a devastating effect on the online sex–work economy.

In the exhibition, artists Lena Chen and Maggie Oates give gallery-goers a first-person account of this law’s effects in their videogame “OnlyBans,” a play on the popular online sex work site, OnlyFans. The game lets players act as an online sex worker where they post nude photos to earn a living. As a player will quickly realize, however, the game isn’t so easy — it barely lets users post one photo without shadow-banning or removing their account. But “OnlyBans” isn’t just a normal game with made up characters and stories, it tells the stories of real sex workers whom this law has affected. When players select a photo that gets taken down, they are shown the real-life story that the dilemma in the game is based on.

M. Nicole Horsley, assistant professor in the Center for Study in Race, Culture and Ethnicity, brought the students in her Black Sexualities course to see the exhibition. She said hosting “On Our Backs” at a predominantly white institution (PWI) like Ithaca College is impactful because it displays elements of Black sexuality that aren’t normally portrayed in mainstream media.

“I think that the realities [of a PWI] become very apparent for students when they go into [the gallery],” Horsley said. “It’s a different kind of engagement … because there’s a Black body on display for white people. And then what is the engagement around that? Is it a fascination? An oddity? A freak show? So these kinds of questions came up when the students went into the exhibit … because the majority of the people who are going to see this aren’t going to be people of color, it’s going to be white people because we are at a PWI.”

Senior Gaby Tola is a student in Horsley’s Black Sexualities course and visited the exhibit with her classmates. She said hosting this exhibition at a PWI is especially powerful in the ways that the collection goes beyond what students might learn in queer and race theory classes.

“In a lot of theory classes, you’ll read about oppression in political ways that don’t necessarily center on the actual idea of pleasure,” Tola said. “So pleasure tends to get dragged out a lot of these conversations and things that we do … so how does that translate especially when it’s tied into the idea of reclamation of the body and agency, especially because it is so antagonized by the government. So I think that beyond just talking about sex, placing nudity, queer bodies, Black and brown bodies, on a PWI sparks that conversation.”

Junior Justin Foster also visited the exhibition with Horsley’s Black Sexualities course and said he was excited to see a more accurate portrayal of people of color sex work because of the way white sex work is often glamorized in mainstream media.

“I thought it was fascinating to see sex work, especially POC sex work in a PWI,” Foster said. “Because it’s one thing to see the same images of the sex work that’s very whitewashed and very glamorized. But seeing what I felt to be a more authentic portrayal of sex work and sexuality on a campus like Ithaca was very powerful and something that I didn’t think IC could pull off.”

Horsley said that she is pleased with the way that she’s seen people respond to the exhibition so far and that the gallery has sparked an educational conversation on the campus around race and sexuality.

“Because this is an educational institution, it should educate, it should expose, it should bring people to these other kinds of engagements,” Horsley said. “And I commend us for being able to to have these kinds of conversations and it not be a problem, that people aren’t out there picketing and boycotting, but actually celebrating and enjoying and asking critical questions, as we should, as a community be asking around race around sex and sexuality, touching skin, all of these things. And so I think that’s happening with this particular exhibit.”