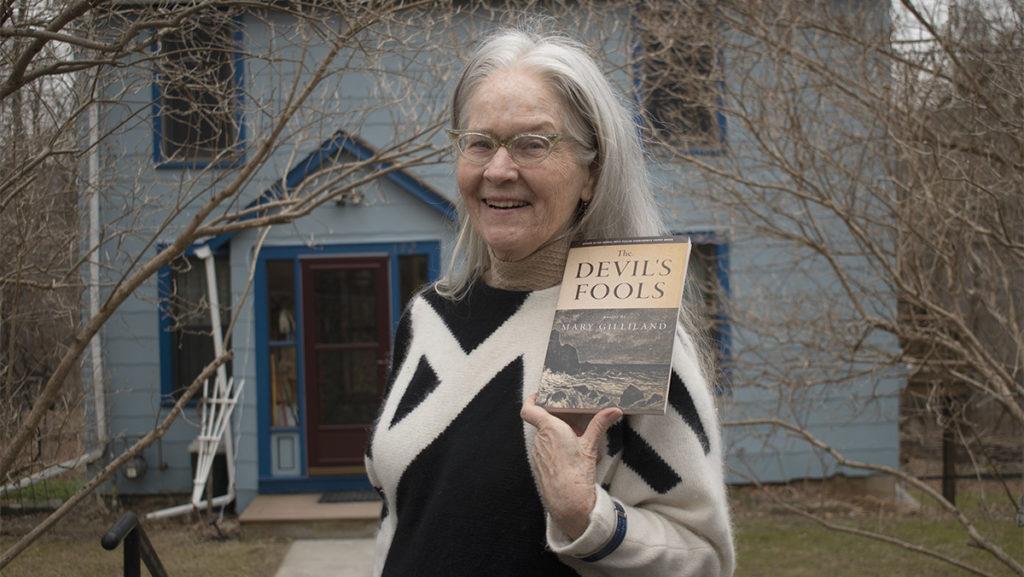

Mary Gilliland, a former professor of both Cornell University and the Ithaca College Department of Writing, released a new poetry collection in December 2022, “The Devil’s Fools.”

Gilliland is the author of two previous poetry collections, “Gathering Fire” (1982) and “The Ruined Walled Castle Garden” (2020). Much like the interdisciplinary writing courses she taught as a professor, her newest collection merges myths with epidemics, environmental crises and musings on marriage.

Contributing writer Rowan Keller Smith spoke with Gilliland to discuss “The Devil’s Fools” and her career as a writer.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rowan Keller Smith: Would you like to tell our readers a bit about yourself and your new poetry collection, “The Devil’s Fools”?

Mary Gilliland: The book is described in different ways. It’s a collection of poems that has several different concentrations as it goes along, and those include weaving new myths out of old ones. There are also a stretch of poems that were occasioned by a residency that I had in Scotland. That was such a joy to go there because that’s my ethnic background and I had never been there. When I was on that residency, there was a horrendous epidemic among the livestock and an even more horrific government response to it, so that occasioned the slaughter of millions of animals and the extinction of many farms. And so, there are poems that are set in holy places in Scotland, but then also poems about this excruciating modern experience of, in a sense, having a business approach to what happens when there’s a crisis. There are also poems about marriage and long-term relationships. I could go on; there’s great environmental concerns in it and there’s a little bit of play with the concept of the devil and the devil’s fools and who exactly that is.

RKS: That actually leads into my next question, what is the story behind the title and how did you come to choose this specific title?

MG: There’s a poem in “The Devil’s Fools” in which I was playing with the kinds of things that happen when, say, you’re at a desk and you’re writing and it’s terribly hot, shall we say? And it’s hard to concentrate, and I’m looking around the room and a lot of the things that are things I brought back from traveling and special places, and then the oppression of the heat wave, the poem’s actually called “Heat Wave.” … Also, in the book, we have Eve in the last poem in the book, and there’s a poem amid that foot and mouth epidemic series that is simply called “Cain.” It is spoken in the voice of Cain, and one of the things I do as a poet is to just inhabit the speaker. … Anyway, to go to the Greek mythical poems, the poem about Odysseus is really sort of ironic about his decisions. And so, gradually, I think with all the human foibles that accumulate in the book, we’re all walking around being the devil’s fools in a sense.

RKS: You retired from teaching at both Cornell University and Ithaca College to dedicate your time to writing entirely. How has your writing process changed since your retirement?

MG: The wonderful thing is that there’s time and space for it. … I did not want to go near teaching, but in Ithaca, there’s a certain way to make a living and teaching is a big one of those, and so it just started happening. My own sort of flow of words was constantly being cut off or interrupted. I was a very devoted teacher, I loved working one on one with my students and with their words. I would say that the main change in the process is that when I wake up in the morning, I’m free. And I know that and that’s most times where I go, is to whatever is happening on the page.

RKS: Are there any moments in time where you have found yourself finding the most inspiration from a certain topic?

MG: There are many forms of inspiration or ways of inspiration. When I was at that little place in Scotland on that residency, I was writing about Egypt where I had been a few years before. I don’t sit down and say, “I’m going to write about this.” It’s like the language starts and it eventually tells me what I’m writing about. There are great moments of inspiration as I’m revising and editing. My process for a poem is I get it started and then I’ll go back to it, and I’ll go back to it, and I’ll go back to it. These are probably intervals at every day for a sequence of days, or I’ll deliberately not look at it for a while. … Sometimes the greatest joy of inspiration is the surprise that comes in.

RKS: How would you say this book differs from your past work?

MG: The question sort of assumes that a poet starts a career by publishing fairly young and then bringing out another book every few years. But I kept poetry a vocation rather than going the career route. Consequently, in the past decade or so, I’ve been finishing reams of interrupted poems as well as writing new ones. Thus, I am free to pull and arrange each collection, thematically and tonally, from poems composed in many different years rather than from those written during a confined chronology. That said, this fall, a chapbook of mine will be published that’s radically different: a continuous poem that continually plays with form.