On Jan. 21, Ithaca College will host its annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration. The celebration will honor “Dr. King’s impact on the world,” according to the college’s online description of the event.

That Dr. King played a central role in the Civil Rights Movement is indisputable. However, there were many other individuals who furthered the movement before Dr. King’s entry, during his rise to national prominence and after his murder.

This was an important understanding I came to as I traveled with my fellow first-year MLK scholars on a Civil Rights tour of the Southern United States. We visited locations that were historically significant to the movement such as Selma, Alabama. While on the tour, we spoke with foot soldiers of the movement — the everyday people who were present and participated in demonstrations like the Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, march. The police’s violent reaction to the protest later earned it the name Bloody Sunday.

Hearing these stories and the emotions they inspired nearly 50 years after the events was an experience beyond words. There is no way to fully convey the agony of the movement and the hope that nonetheless persevered. While many of us have learned about the Civil Rights Movement in school, we have been denied true understanding of the suffering behind the struggle. Children were bombed in Birmingham, Alabama, and beaten on Bloody Sunday.

We visited the 16th St. Baptist Church in Birmingham that was bombed by the Ku Klux Klan and walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge where Bloody Sunday took place. Experiencing it firsthand was completely different from learning about it in class.

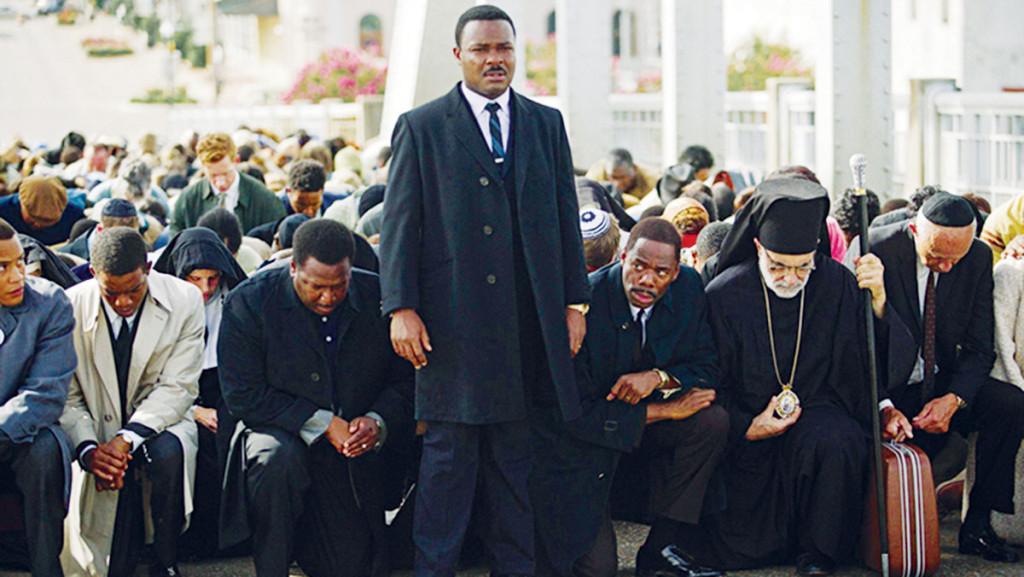

So when I heard about the motion picture “Selma,” I hoped for a movie that would elicit the same emotions. Part of the power of film is that it inspires empathy and draws the viewer into the complexities of the story. However, I was also wary given the tendency of media to whitewash and simplify history.

The movie “Selma” quickly dispelled my fears. Directed by Ava DuVernay, the film centers on the perspective of Dr. King, but in an intentional and appropriate manner that incorporates the stories of foot soldiers such as Jimmie Lee Jackson, Annie Lee Cooper, Viola Liuzzo and the unnamed masses.

“Selma” humanized both Dr. King and President Lyndon B. Johnson, who is typically portrayed as the hero-president of the Civil Rights Movement. The film has sparked controversy because DuVernay “wasn’t interested in making a white-savior movie, [she] was interested in making a movie centered on the people of Selma,” as she told Rolling Stone magazine.

What DuVernay has done is refused to glorify a political system that does not work, or works too well at systematically oppressing people of color. She represents the pros and cons of democracy, and how at its core it requires the engagement of the masses. When the masses are not engaged, democracy fails. That is why the right to vote was so important.

Watching “Selma” we easily recognize that African-Americans’ human rights were violated, and we empathize with protesters’ strategies, including those that were considered radical and disruptive at the time.

So what, then, is the difference between marching 50 miles in 1965 in pursuit of voting rights against the wishes of local whites, and blocking traffic in 2015 to insist that Black Lives Matter? Blocking traffic now feels too close to home. We can easily imagine the places we would be zooming off to before a group of “inconsiderate” protesters stood in our way. Instead of getting stuck on the inconvenience of activism, a better strategy is to look at these actions as if it were 50 years later and give them the same respect and consideration we now give the Civil Rights Movement.

Marlena Candelario Romero is a freshman exploratory major. Email her at [email protected].