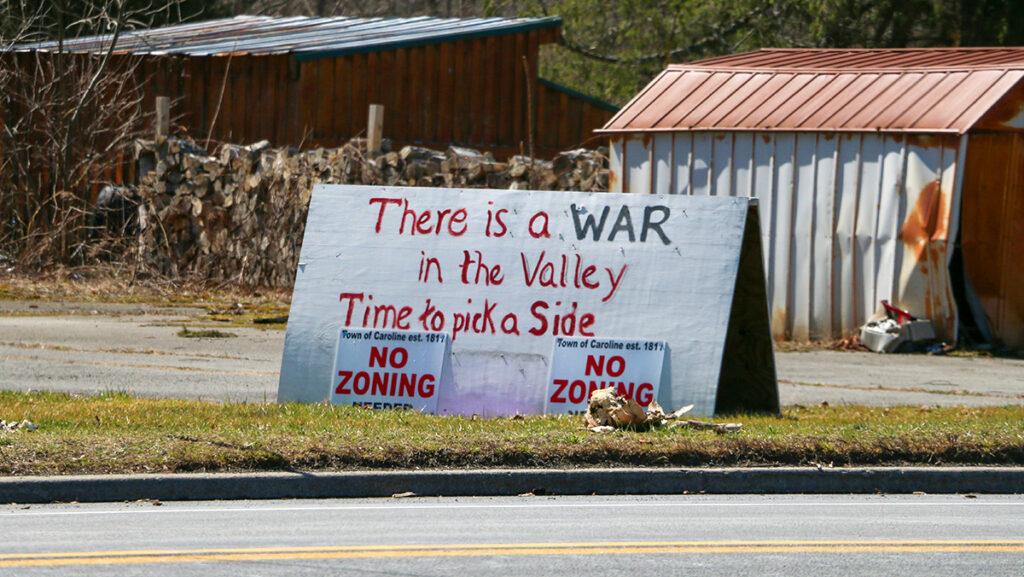

Over the past year, the Town of Caroline has been divided on the issue of zoning. In town, the arguments have publicly presented themselves as yard signs with messages like, “Grandma hates zoning” and “Caroline for responsible zoning.”

Caroline is a neighboring town of Ithaca, located in Tompkins County. It is a rural farming town of 3,368 residents that has been unzoned since its founding. Zoning is the common legal practice of dividing land into different districts, like commercial or agricultural zones. Zoning would be implemented in the town for environmental reasons, like protecting its natural resources, maintaining the rural nature of the town and promoting Caroline as a positive community to reside in, according to a 2021 document outlining the purpose of zoning in Caroline.

The draft of the report divides the town into four main zones: an agriculture/rural district; eight hamlets, which is a rural settlement smaller than towns or villages; a focused commercial district; and a water resources and flooding overlay district, according to the map on Caroline’s website.

On March 23, residents who are against zoning submitted a petition with 1,228 signatures to the Town Board, Caroline’s local government. In the petition, the residents demanded the board hold a pause on zoning for a period of two years so that residents can fully understand the implications of a zoning ordinance.

“This is critical in that a town law of this magnitude will affect every current and future land owner in Caroline by removing freedoms that our community has enjoyed for over 200 years since our founding in 1811,” the petition stated.

This petition was signed and presented to the Town Board in response to a draft of the zoning law that was created by the Zoning Commission. On Jan. 31, the Zoning Commission officially released the final preliminary report for zoning. On March 27, the final version of the report was presented to the Town Board.

The Zoning Commission was a committee appointed by the Town Board to study zoning in the town. Once the Zoning Commission completed the draft as a final document, it was disbanded. This commission was formed on the basis of the Comprehensive Plan that was updated in 2021 to reflect the vision, mission and goals of the town. The Town Board will soon vote on whether or not to implement zoning. Only the town board votes on a zoning law and individuals do not, according to New York State law.

RC Quick, a resident of Caroline, said he is a sixth-generation landowner and his family has owned land in the town since 1864. Quick said he feels that zoning in Caroline is unnecessary because the town has pre-existing building requirements and code enforcement laws, which is appropriate for a town the size of Caroline.

Quick said that even though 1,228 people signed the petition, this data is not reflective of the anti-zoning sentiments in town.

“There is a responsibility, I would think, of the town government to listen to its constituents,” Quick said. “And nothing could speak louder than a petition with 1,228 signatures, which is 38% of the town’s population and doesn’t include the 600 children who are under voting age. So that 1,228, for me, it becomes a much higher percentage.”

While Quick is against zoning, he said he is more affected by the atmosphere of the town, amid the debate.

“The sadder thing, to me, [is that] this whole situation has torn the town apart,” Quick said. “And it is very, very unfortunate and sad and it makes me want to weep.”

John Fracchia, career engagement and technology specialist at Ithaca College, is a resident of Caroline and served on Caroline’s Town Board from 2014–21. Fracchia said laws around land use were discussed later in Caroline when compared to laws that were passed in other urban and suburban areas.

“With this issue, what I’m observing is [that] the community is really struggling to figure out, ‘Who do we want to be, how do we want to be, what’s the best way to preserve our resources to have a community that people feel good living in, are proud to live in?’” Fracchia said. “I think the key disagreement is, how do we get there and as one course of action or another, set us up not to achieve those goals in the future.”

Quick said he was dissatisfied with the composition of the Zoning Commission and is afraid that if zoning is implemented, it can lead to a domino effect of government control.

“It’s ironic, in a way I suppose, that the Zoning Commission originally had nine people, three people were asked to step down … and the Town Supervisor Mark Witmer was encouraged to replace these people but never did or never made an attempt to,” Quick said. “There was not a farmer in the Zoning Commission in an agricultural, rural town. The majority of the Zoning Commission members have a ‘cornell.edu’ email. There was no relatively large, small business owner on the Zoning Commission. … There was no multigenerational landowner resident on the commission. And it was not representative of the citizenry of the Town of Caroline.”

Caroline is only required to have at least one public hearing before implementing zoning, according to the New York State law. However, the Zoning Commission has organized six public information sessions and two public hearings after the zoning ordinance draft was prepared.

Bill Podulka, chair of Caroline’s Planning Board, said the Town Board appointed every individual who applied to be a member of the Zoning Commission, except two individuals who applied but did not reside in the town. Podulka said that if more residents had been involved in the process, representation in the board could have been worked on.

“First off, in a small town, it’s often really hard to get people to step up to the plate and do stuff,” Podulka said. “Bottom line is: when the Zoning Commission was appointed, had other members of the community stepped forward on it, they probably would have been appointed.”

Fracchia said that while zoning has proven to be problematic in the past, zoning laws in Caroline are being developed not to discriminate but for the sake of the town’s resources.

“If you look at the history of zoning laws, they’ve been used nefariously to discriminate, which is not something I would dispute,” Fracchia said. “What I would dispute is whether that’s applicable to our community. I could also make the case that areas that have not had any of these protections in place often become the victims of mass industrialization, contamination resources, and those are often the most economically vulnerable communities.”

Quick said that having autonomy over his own land helped him recover from his alcoholism.

“I came back to Ithaca and was going through some tough times,” Quick said. “I’m an alcoholic. And I attribute a lot of the reason for my 40-year sobriety to the land that I own in Caroline and the woods that I am allowed to walk in and work in.”

Podulka said that while talking about autonomy over land, people must consider the consequences of how they use their land.

“And this is sort of the core of the issue: that there is the one side that says, ‘Personal property rights, I can do what I want in my property,’” Podulka said. “The other side of it … [is] we are a community. And the community has to work to the benefit of everybody because what you do on your property may, and often does, impact the properties next to you.”

Fracchia said that while he does want zoning, he does not want too much of it.

“So my involvement has been evolutionary,” Fracchia said. “I’ve come to believe yes, we do need some form of zoning. … I found that many of us who feel more like I do don’t want a high level of zoning. We want what we’re calling sometimes ‘skinny zoning’ or ‘responsible zoning.’”

Fracchia said that zoning is not a tool to limit Caroline residents’ autonomy but to preserve the nature of the town in a sustainable and safe manner.

“From my lens, I’ve used zoning as not to restrict who lives in our community but to make sure if they do live in our community, they have access to affordable housing, they have access to land resources to use as they hope to and that those resources aren’t contaminated, that there’s adequate water [and] if they wish to farm, they have land that they can [use],” Fracchia said.