Director of Orchestras Jeffery Meyer first traveled to Southeast Asia in 2008 to work with the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra, the Philippine’s leading orchestra and a top music ensemble in the Asia-Pacific region. Meyer then traveled back to the Philippines to conduct a masterclass and a concert with the symphony orchestra FILharmoniKA in 2009. Meyer has also worked with the Orchestra of the Filipino Youth, an organization that helps children in need learn about discipline and community through a musical environment.

In January, Meyer traveled to Thailand to conduct the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra for the first time. This performance included works by Debussy, Copland and the Taiwanese composer Narong Prangcharoen. Meyer also recorded the Thailand Philharmonic’s first international commercial recording which will be released later this year on Albany Records.

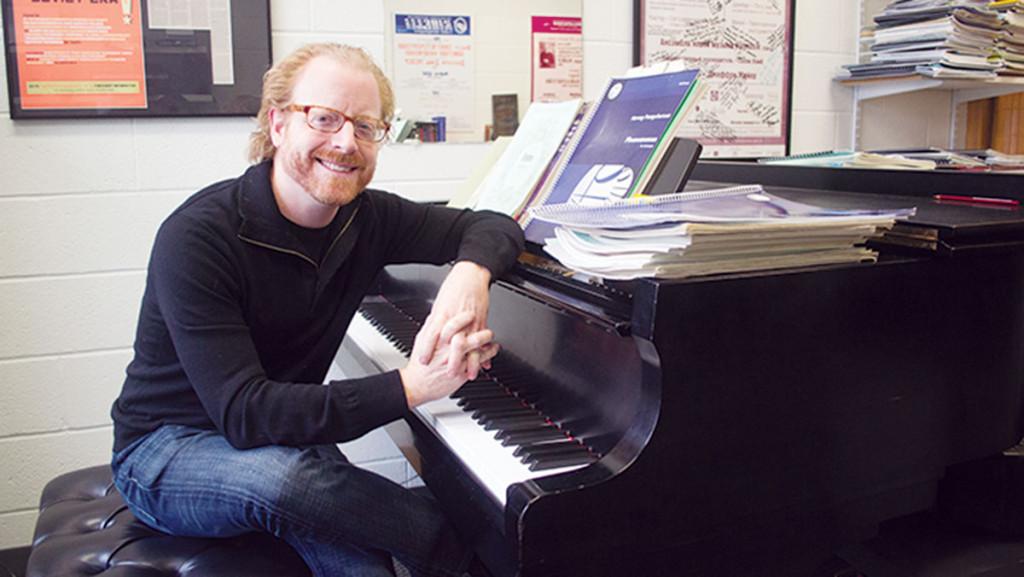

Staff Writer Ashley Wolf spoke with Meyer about the international language of music, conducting and his international relationships formed through his international conducting experience.

Ashley Wolf: Why did you start conducting internationally?

Jeffery Meyer: A conductor named Darrell Ang, who is a very well-known Singaporean conductor now, tried to get me a gig in St. Petersburg, Russia, to do a guest concert with one of the orchestras. It was going to happen, I had soloists picked out, but it fell through. We began talking and decided the time was right in St. Petersburg to start an orchestra from the ground up. St. Petersburg is a very important and cultural musical city, but in terms of orchestral programming and playing, it’s very conservative. They do a certain canon of repertoire and don’t reach out outside of that. So, we wanted to start an orchestra that was more progressive, and we did. We took that one concert and looked for sponsorships, looked for grants, looked for projects, and it’s been going for 12 years. That was the beginning of my international work.

AW: How did you start working in Southeast Asia?

JM: There’s a composer named Chen Yi who grew up in the Cultural Revolution. She is one of the first Asian women composers to become internationally recognized out of China. I found her music years ago, really liked it and was programming it in various places. I got in touch with her, and she’s a very good communicator. So we had been communicating for years, and she noticed I was interested in 20th-century music and music of our time, so we began a professional relationship. Then a few years back, she was in charge of running a competition festival at the Beijing conservatory in Beijing, China. They invited me to become the conductor there, conducting a lot of new works for a smaller ensemble and as things work, once you start going to a place and doing good work, people know you and you meet people, and those relationships turn into additional opportunities. I’ve gone to China now a half a dozen times, working in different places often through Chen Yi’s influence.

AW: What was the most recent conducting job you did in Asia?

JM: Most recently, I was in Tianjin in May for 10 days. There was this very intensive, orchestral training period with the Tianjin Symphony Orchestra. One of her students, who I was recording, Narong Prangcharoen, is Thailand’s most important young composer, and he started the Thailand International Composition Festival. I went there first in 2012 primarily because Chen Yi introduced me to Narong, and Narong runs the festival. That began my relationship with this orchestra. While I was there, I worked with the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra, that was in 2012, and since I’ve been invited six times. We got along well — the working relationship was good. The orchestra is growing and is one of the best in Southeast Asia and that led to this recording project of Narong’s music.

AW: What are the similarities and differences between an orchestra in America and an orchestra overseas?

JM: The interesting thing is that there’s not much difference. If you’re doing your job as a conductor, you’re not there to be speaking very much. You’re there to be communicating through the way you move and gesture. Everyone who’s in an orchestra has been trained in this particular kind of language. It’s a whole different language than our spoken language with various conventions and various signs. They know how to speak that language, I know how to speak that language. Very quickly, it works just like anywhere else.