At an elevation of 8,000 feet near Laramie, Wyo., Ithaca local Gerard H. Cox stood over his fresh antelope kill. It was a hot day in September of 2000, and the meat threatened to spoil if he didn’t quickly remove the animal’s innards.

Cox glanced at his wristwatch, but found that he was unable to read the time, as the watch was covered in blood.

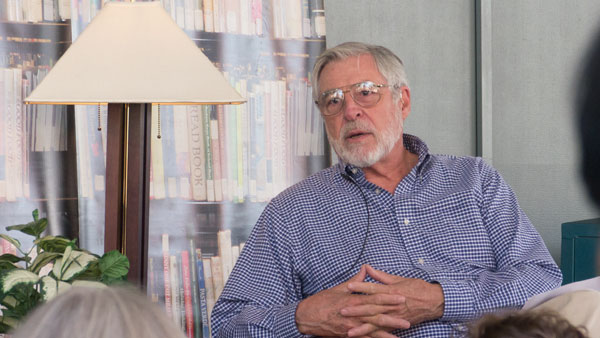

“And out of my mouth, aloud, came the words, ‘I have blood on my hands,’” Cox said. “Now why did I say that? I have no idea.”

The experience led Cox to delve into research on blood — how other people and cultures think about blood and how people see animals. Though Cox didn’t know it at the time, this research marked the inspiration for his book, “Blood on My Hands: An Ecology of Hunting.”

After about 10 years of research and writing, Cox’s book will be released this fall through Dog Ear Publishing, an Indiana-based, self-publishing company.

Cox said the book addresses an ethical defense of hunting, not only as an important role in the cycle of life and death, but also as a way for people to attain and enlarge an “ecological consciousness” of nature.

Cox said his experience with the antelope helped him realize that because he hunts to provide food for his family, their ability to live is due in part to that antelope’s death.

He said he felt compelled then to thank and honor the animal when preparing it for friends and family to eat.

“I treat hunting not as an end, but as a means to gain a larger consciousness of who you are and where you fit in with all the other forms of life on Earth, and that’s why it’s an ecology,” he said.

Cox said humans and animals share DNA, making us all inherently related.

“That should make a difference on how we treat these other animals, I argue,” he said. “That’s where the ecology comes in — we’re all in this together.”

In practice of this philosophy, Cox said he does not hunt for trophies. He said he appreciates the value of hunting for its naturalistic aspect — honoring the acquired meat when providing for his family and appreciating the ongoing life cycle.

“I would like my death to benefit some other creatures,” he said.

The Rev. Dr. Douglass Green, fishing partner and Ithaca local, said Cox’s work is spiritual and fascinating for both hunters and non-hunters.

“He’s a very knowledgeable person, not just in fishing, but in all aspects of life and how they relate and tie in to what one is doing,” Green said.

Cox comes from a long family history of hunting, with his parents having been bird hunters. His first experience with bird shooting occurred before he was old enough to carry a gun, he said.

His family moved from New Canaan, Conn., to Seattle, Wash. in 1953, while Cox continued boarding school in New Hampshire. He earned his undergraduate degree at the University of Washington and later returned for the first half of his career, working as an English professor after having served in the Navy and earning his doctorate at Stanford University. He moved to Ithaca in 1982 to take up the position as assistant dean in the College of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University.

Cox was a part-time instructor in Ithaca College’s writing program during the 1983–84 academic year. His wife Caroline Cox worked in the college’s development office as the director of major gifts. She retired in 2006 after 22 years at the college.

It was at Cornell that Cox met James Caldwell, a then-graduate student pursuing a computer science degree at Cornell. Caldwell and Cox found each other in 1996 through a fly-fishing mailing list and, after realizing they lived in the same town, decided to get together to fish, Caldwell said.

Caldwell moved to the University of Wyoming toward the end of the decade, where he is now the department head of computer science. He said Cox often visited there so they could hunt and fish together. The antelope episode that spawned his initial book research occurred during one of these excursions.

“He felt some remorse for the animal, which not all hunters feel, but he was also thankful,” Caldwell said. “The book describes better what he felt because he reflected on it for a long time and was very careful to write it down.”

Cox said his writing process did not follow a pre-determined, organized structure.

“It took me a long time to realize I was writing a book,” Cox said. “I’ve learned that writing helps you figure out what you mean.”

The ecological consciousness of nature that Cox discusses also relates to appreciating the fact that big-game animals, such as deer, have the upper hand in their own habitat.

“These animals know the country a lot better than you do,” he said. “When you hunt, you’re not going through the landscape — you’re in the landscape.”

Cox first tried deer hunting with Caldwell, and they both had experience with backpacking and rock climbing. But there is a significant difference in how these activities relate to nature versus how hunting relates to nature, Caldwell said.

“When you are a hunter, your relationship changes with nature — you become part of it in a different way,” Caldwell said. “When you become the predator, you become part of the whole system in a way that’s very difficult to describe unless you do it.”

Cox also writes “Hits and Misses,” a blog on hunting, fishing, cooking and other aspects of life. Check it out at gerardcox.blogspot.com.