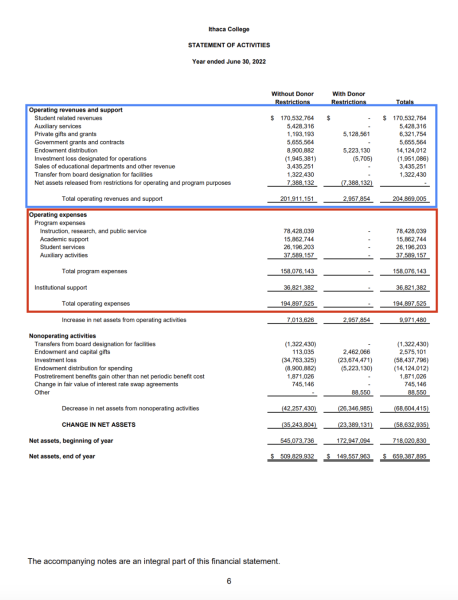

Besides the Form 990, one essential form for looking at a nonprofit’s finances is the audited financial statement. Each year, Ithaca College releases its statements for the previous fiscal year. One major data point on the statement is the college’s operating revenue and operating expenses, which are used to calculate if the college is in an operating surplus or deficit.

Operating Revenue and Expenses

Operating revenue is a general category for smaller streams of revenue for the college. Operating expenses is a general category for smaller categories of the college’s expenses, specifically relating to the college’s operations and daily functions.

The subcategory with the largest amount of revenue is student-related revenues, including payments for tuition and fees. Investment loss designated for operations — a negative number in the revenue section — is an amount pulled from investment accounts to pay for operations.

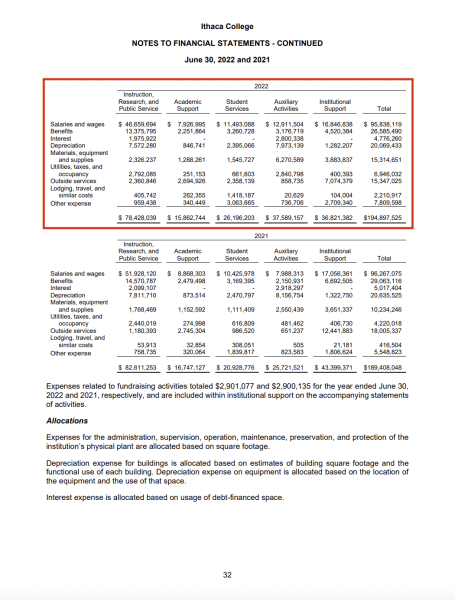

Operating expenses are further divided beyond the “Program expenses” subcategory.

Salaries and wages are the highest expense, particularly salaries and wages for instruction, research and public service. This includes faculty and staff salaries.

Sean Kanazawich, controller in the Division of Finance and Administration, said the expenses for buildings and land may not show up in their full amounts because the college will capitalize and depreciate the expense, meaning the college pays off a large sum over time.

“[For example] you might buy a building for 30 million,” Kanazawich said. “Over 20 years, you’ll see expenses like 1.5 million each year. … There’s some large purchases that won’t necessarily be fully shown in that one year when you’re measuring those operations.”

Where to find the operating surplus or deficit amount

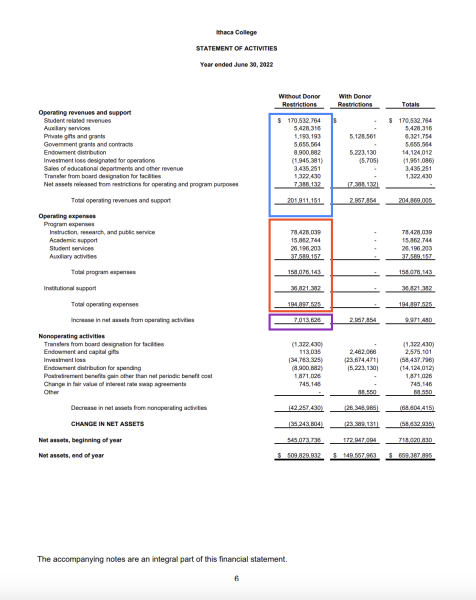

Tim Downs, chief financial officer and vice president of finance and administration at the college, said that when trying to find if a college is in an operating surplus or deficit, the audited financial forms provide the most accurate information, so when he presents the college’s finances, he uses the Statement of Activities on the audited financial forms.

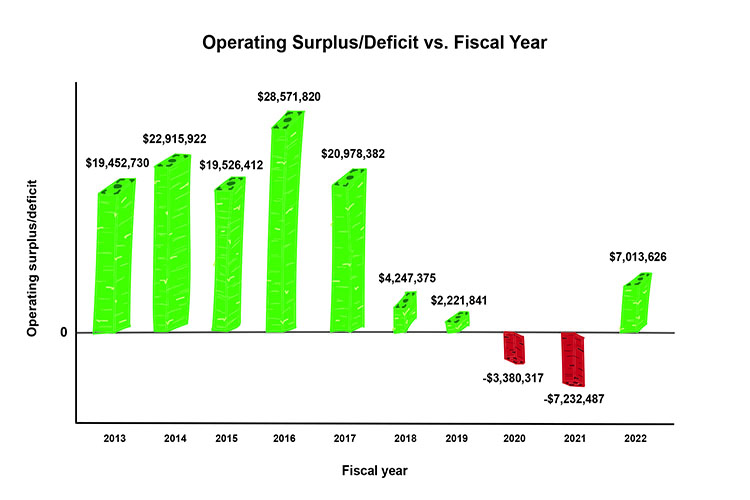

The blue box indicates the total operating revenue for each category without donor restrictions. The red box indicates operating expenses. The purple box is the total amount of operating expenses subtracted from the operating revenue. On the 2022 audited financial form, the college is in an operating surplus of $7.01 million.

Downs said the Form 990 shows a revenue less expenses amount that is similar but not exactly the same as operating revenue less operating expenses, because the Form 990 also includes some nonoperating activities.

Kanazawich said some of the nonoperating activities that are taken into consideration on the Form 990 but not the audited financial statements include endowment distribution, transfers from the Board of Trustees designation for facilities, investment loss and unrealized losses on investments.

Downs said he does not take into account the revenue with donor restrictions because financial officers at the college have the most control over the funds without donor restrictions and therefore those have the most impact on daily operations. He said he primarily looks at operating activities rather than nonoperating activities when discussing the college’s surplus or deficit.

“You’re probably never going to see me give a presentation that covers [nonoperating activities] because it’s not driving our day-to-day,” Downs said. “It’s literally a book entry. I increase the asset and I increase the liability.”

For the purpose of this article, only the audited financial forms for the college will be used when discussing operating budgets.

Debt vs Deficit

Debt is a legal instrument that is borrowed, like a loan, and has to be paid back. Deficit is when revenue is less than operating expenses.

“Debt is very well laid out and we went and entered into legal obligations and that means no matter what happens, I have to pay this money back,” Downs said. “So each year, I have a stream that I have to go pay.”

What the college does with money from a surplus

Kanazawich said that because the college is a nonprofit, any surplus — also called net income — is put back into the organization. He said people in management positions would decide what to do with the money. Management positions include CFOs, like Downs, vice presidents and associate vice presidents.

“Management’s going to make all those decisions and the world is their oyster,” Kanazawich said. “You could throw all that money into the endowment. … You could take that money and pay off some of your debt early, maybe it’s too–high interest. You don’t want to have [that debt]; save yourself money. You can just hold on to that money for now as an operating [expense] cushion. Just throw it in an investment account. It’s not really your endowment but more of an account that’s going to bolster your own [budget].”

Downs said the college gives the money to an investment person or firm and they invest it for the college. Kanazawich said money can be invested in two different ways: in the endowment or for operations.

“To invest it in the operating investments, you’re just going to boost your operating investment income in future years, which just helps you have more operating income, whereas endowment investments don’t really give you operating income, per se,” Kanazawich said.

Downs said decisions about the college’s surplus usually go back to the Board of Trustees. However, because the college is operating out of two years of deficits — fiscal years 2020 and 2021 — the money from a surplus would be used as cash to manage the deficits.

“[In the past, finance officers] say to the board, ‘We had $10 million of surplus this year,’ and the board would say, ‘Okay, put some toward the endowment, put some toward a capital investment, put some back in cash,’ [and] they would then make the determination where to put it,” Downs said. “Right now … we’re running deficits, we’re basically putting [the surplus] in and out of cash until we get back into a place where ideally we have systemic operating surpluses.”

Jesse Wheeler, co-managing partner at Davidson Fox Certified Public Accountants, said every nonprofit manages its endowment differently and develops its own investment strategy. He said endowments have different types of money put into them with different rules. One of the ways an endowment grows is through traditional endowments.

“A true endowment is me saying, ‘I’m giving you some money I want you to set aside,’” Wheeler said. “So I’m going to give you $10,000 and you can never spend that $10,000. You can spend the earnings on that $10,000 a year for a scholarship.”

Wheeler said the board-designated or quasi-endowment is when the Ithaca College Board of Trustees decides to set aside extra money, like the year following an operating surplus, and creates an internal endowment for specific purposes.

“[A college] might have said we want to preserve 100 million dollars for scholarships, or we want to preserve $100 million for maintenance of the campus buildings, and we’re going to create this internal endowment just for that purpose,” Wheeler said.

What the college does if it is in a deficit

Kanazawich said that when the college is in an operating deficit one year, the college can recover by relying on other years when it was in a surplus. For example, on the 2021 audited financial statement, the college was in an operating deficit of -$7.23 million, and the previous year was in an operating deficit of -$3.38 million. For at least back until 2008, which is the earliest the college’s website lists the audited financial statement, fiscal years 2021 and 2020 were the only years with a deficit.

Downs said that when the college is in an operating deficit, it can pull money from its investments to help fill the gap between operating revenue and expenses. The non-endowment investments, totaling $99.27 million in the 2022 fiscal year, can be turned into cash (liquidated) for operational expenses based on the Board of Trustees’ investment policy — outlined in section 1.1.3.7 in the board’s policy manual. The Board of Trustees sets limitations on what kinds of investments the Division of Finance and Administration can purchase and how they are sold. For example, the college cannot purchase high-risk investments without board approval, and its current investment portfolio is primarily lower-risk investments.

“Most of our [non-endowment] investments are in fixed income, [so] we wait to maturity,” Downs said. “As soon as they mature, they become cash. And then we either roll them over into a new bond fixed income–type instrument, or we just let it sit in our cash account once it matures.”