Editors Note: This story begins a new series of long-form features that break away from traditional newspaper style by using artistic techniques and literary elements to present an in-depth look at life in Ithaca. In producing these stories, our writers spent substantial time in the worlds of their subjects to understand them on a deep level and attempt to capture their essence. This series will highlight individuals who are not necessarily traditional newsmakers, but have found passion and meaning in their lives as members of the community.

It is Dec. 1, 2014. A group of Ithaca College students have had enough of talking. They have been talking for months, about the shooting of unarmed black teen Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in August. About the murder of unarmed black man Eric Garner. About the fact that both officers responsible for the deaths were not indicted for the crimes. About Ithaca’s own Shawn Greenwood, a black man killed by police officers in a 2010 narcotics investigation. About microaggressions and ignorance on campus. About inequality in general.

Across the U.S., at 1 p.m. EST, the “Hands Up Walk Out” movement is about to begin. Michael Brown’s death occurred at this exact time Aug. 9, 2014. Because of conflicting evidence, and only one person alive to tell his side of the story, many people felt that justice had not been served, that justice was not served in many of the other cases mirroring this one.

The sky is clouded, and the air is cold. Senior Steven Kobby Lartey, bundled up in a navy blue jacket and scarf, walks to Free Speech Rock just outside the Campus Center. He can see his breath in the early afternoon air. The rhythmic beating in his chest has sped up only slightly, but he can still feel its effects.

“I was like, ‘Will people come out? Will we have a unified voice?’ — and I don’t mean unified voice like everyone wants the exact same things, just in general — ‘Will people stand in solidarity?’ ‘Will campus police even allow us to congregate?’” Kobby said.

The questions did not stop him. They did not stop anyone. Just after 1 p.m., some 200 Ithaca College students walked out of their classes as agents in a nationwide protest.

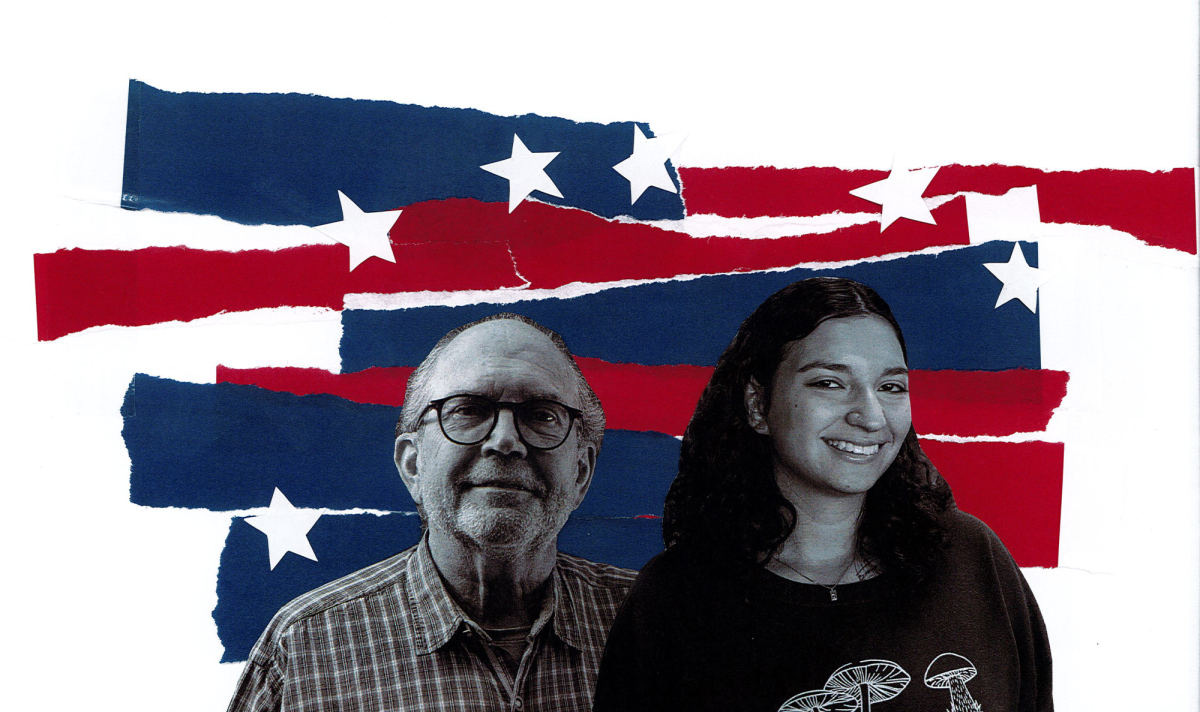

From left, Kobby, seniors Kayla Young and Crystal Kayiza and sophomore Vin Manta hang up a sign at the Hands Up Walk Out demonstration Dec. 1, 2014. The demonstration was part of a nation-wide solidarity protest in honor of victims of police brutality.

Kobby, along with senior Student Government Association President Crystal Kayiza, senior Kayla Young and sophomore Vin Manta hang a large, red poster up on one of the brick walls of the building. The black, painted lettering reads “HANDS UP DON’T SHOOT,” bookended by a pair of dripping, black handprints.

Young is standing at the front, facing the crowd. Armed with a white and red microphone held close to her mouth, her voice is shaking.

“For four and a half hours, Mike Brown bled to death on our pavement,” she said. Her eyes are lowered. She reads off of a prepared note card, but that doesn’t change anything. Her voice is shaking, but not with fear. “Mike’s story affects us in so many ways. As Ithaca College students, it gives us more purpose than simply being students on a conveyer belt, comfortable in oppression. We walked out today because we believe all lives matter, no matter who we are, and that we must be treated with dignity.”

We walked out today because we believe all lives matter, no matter who we are, and that we must be treated with dignity.

Kobby is behind Young, staring out into the crowd. He stands humbly, hands folded in front of him as he leans against one of the low walls that circle Free Speech Rock. He is quiet. It is not yet his time. When she finishes speaking, he takes the microphone from her.

“We hear you, we cherish you, we hear your stories,” he says into it. The crowd chants it back with him. “We hear you, we cherish you, we hear your stories.”

———

It is 2000. The town is called Legon, and it is just outside the major city of Accra, Ghana, one of the first Sub-Saharan African nations to win its own independence in 1957. With a population of more than 2 million, Accra is Ghana’s capital and largest city. But North Legon is different.

The University of Ghana is situated just up the hill, standing as a pillar of influence since 1948. The area holds a constant buzz and hum of activity typical of a college town, mixed with a peacefulness lended by the backdrop of soft mountain ranges and blue skies. The morning air smells crisp. North Legon generates an aura of friendliness not seen in the U.S. People are on the street, warm and welcoming; the locals all know each other. The kids hang out at Adjei Mensah Supermarket on the corner after school, talking to the owner. He sometimes gives them snacks, free of charge.

Kobby is 7 years old. His two parents, a mother who is a Ghanaian diplomat and a father who is a financial analyst and the CEO of a technology company, are each one of seven children. Kobby grew up with his family. Family and their stories — Kobby said stories are part of being Akan, a West African cultural group.

“In the Akan tradition, storytelling is an important part of family life,” Kobby said. “So my grandfather would always tell these stories, whether real or not they were so fascinating. But I remember vividly one story my grandfather told us, or a couple of stories. It was about Ghana and its history.”

Everyone is together today: Kobby, his older sister Emelia, his younger brother Kojo and a nearly uncountable number of aunties, uncles and cousins. Kobby’s grandfather sits at the center of attention. He usually mesmerizes the children with fun stories about life and history, but it will not be a lighthearted tale this time around. This will be a chilling story, one to teach a lesson: things are not always just.

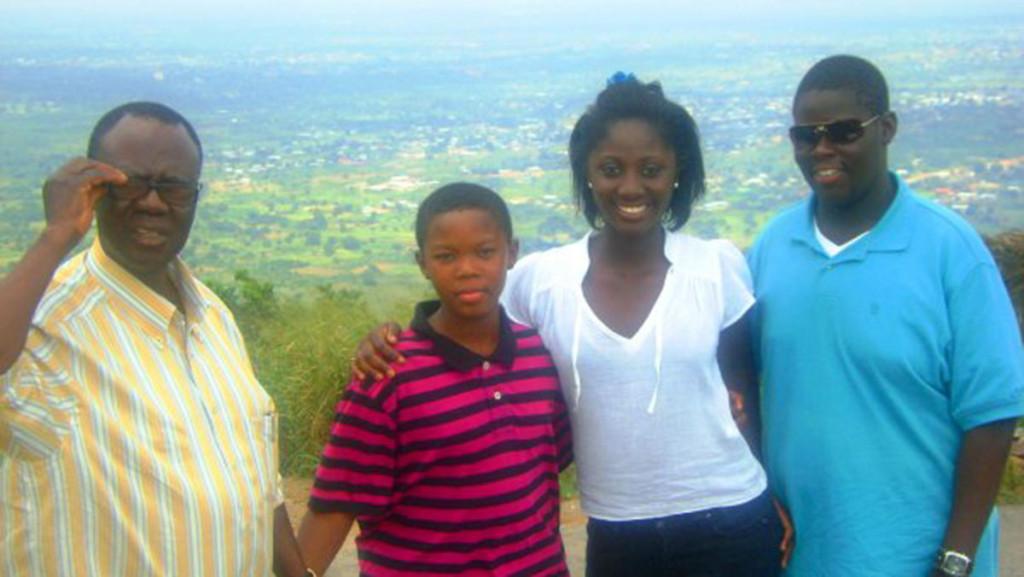

From left, Kobby’s grandfather, Nana Adae-Bosompra; Kojo; Emelia; and Kobby stand together in North Legon, Ghana, where they grew up.

The story begins in 1981. Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings has seized power of Ghana through a military and civilian revolt, replacing Lieutenant General Fred Akuffo. During Rawlings’ regime, Ghana would come to bend to what is now known as “the culture of silence.” The decade was marked by the intimidation of the press and widespread fearmongering, used to keep people in control. People are anxious. They cannot breathe. This is a dark time.

During his lifetime in Ghana, Kobby would not see these kinds of atrocities, he would not live with the same fear.

“I was always running around always being, just living life, so as a kid I was like, ‘What? people were not allowed to do these things? They weren’t allowed to talk?’” Kobby said. But Kobby is 7 years old. His young mind realizes that there is something not quite right about what his grandfather is saying, but he has yet to learn the words to say it.

The story sits in the back of his mind, compartmentalized for the time being. He has to go play market with his sister. They use leaves from the tree in their front yard as currency and pretend to be at the fish shop.

The story of a militarized Ghana would sit and wait for the right moment, along with all the other stories of oppression he would hear as he got older. Somewhere in that timeline, a phrase would be introduced. A chant. A callback.

“Amandla, Awethu,” born out of anti-Apartheid movements in South Africa during the 1990s, a time when millions were forced into segregation — the largest relocation in modern history. A time when armed police officers would forcibly enter homes, load the residents up onto big government trucks and leave. A time when people had to carry around special passes depending on their ethnic background, much like slaves of the area did in the 1800s. A time when blacks could not own businesses in designated “white” districts without special permission. A time when interracial marriage was illegal. A time that did not end until 1994. The phrase means “Power to the people” in Zulu.

———

It is 2015. Kobby walks past Textor Hall at Ithaca College. He’s on his way to the third floor of Friends Hall for one of his classes. As a legal studies major, most of his courses are either in Friends or the business school. If he were in Ghana, the temperature would be a warm and rainy 88 degrees, but here in Ithaca it’s only in the 20s. A foot of powdered snow has covered the ground, soon to be followed by another foot in a couple of days.

Kobby keeps comfortable under cardigans and infinity scarves. He’s not usually one for cold, but today he lightheartedly jokes about a transformation.

“It’s so warm out today,” he says, his pace leisurely. He still has nearly 10 minutes before his class begins. “I never thought I would be one to think 25 degrees is warm, you know how I am about the cold.” As he walks, he waves and says hello to people he knows, occasionally stopping to briefly discuss a meeting or event. People are personable with him, as if they’ve been friends since childhood. It almost seems as if he knows everyone on campus, but he just has that kind of personality.

“As a kid I always enjoyed listening to conversations and listening to people and listening to things and watching things and reading things,” Kobby said. That is partially why he went into the legal field. To learn. To listen. He watched his first election in Ghana when he was still in elementary school. Back in North Legon, he and his siblings would hang out with the owner of the Adjei Mensah Supermarket. He was a 70-year-old man, and much like Kobby’s grandfather, he would tell historical stories about Ghanaian government. Even though he was only in the third grade, Kobby would have debates with him.

“I was always taking these stories and interested by members of parliament who would speak up and have their voice heard, because my grandfather always asked us to be mindful that, growing up, we had people who pushed for systems, pushed against systems, pushed for democracy, pushed for freedom of speech.”

His sister Emelia, now a 22-year-old Marist College graduate working for a creative branding startup in New York City, says back home everyone calls him “Mr. President.” It’s just a joke, yet she said there’s still an underlying feeling that maybe it isn’t.

“A lot of families will say, ‘Oh yeah, this guy’s definitely going to be a president,” Emelia said. “But he’s actually one that, if you ask, eight out of 10 people will say, ‘Well, I think he actually is going to be the president.’ ”

Emelia can’t help but laugh when she talks about her younger brother; her voice is warm and full of the kind of love only an older sibling can have. The kind of someone who knows you and what you’ve become.

“He’s my little brother, but if you ask any of my friends, he’s my biggest inspiration,” she said. “I always try to do more, and I always try to think of how to be an activist, because he inspires me to do that.”

He’s my little brother, but if you ask any of my friends, he’s my biggest inspiration. I always try to do more, and I always try to think of how to be an activist, because he inspires me to do that.

She, too, recalled the stories their grandfather would tell them back in Ghana. About inequality and the culture of silence. About speaking out and having a voice. But now she’s hearing those words somewhere else. Somewhere closer.

“Kobby, now when I have conversations with him, they sound just like that, like when we used to sit down and listen to my grandad talk.”

He has developed the same consciousness as their grandfather had, yet Emelia believes he always had it. Even in grade school, she believed he was always ahead of his time, always thinking about others and about the bigger picture. Yet also never forgetting those closest to him.

“The only thing I want for him is to be true to himself and keep doing what he’s doing,” she said. “Because he’s been doing it our whole lives.”

Kobby said his bracelets remind him of home and the places he’s come from. Though he wears different ones, he’s worn some combination of them every day since his permanent move to the U.S.

On his left wrist, Kobby wears a set of three bracelets. He wears them every day — maybe not always the same arrangement, but they have been a daily part of his look for years. For longer than he can remember. Made of recycled glass, they are hand-painted in warm oranges and yellows, flecked with light greens and navy blues. The patterns vary: stripes, solids, squares. He looks at them fondly, running his fingers along the beads as he speaks.

“For me, it’s to remember where I came from and the depth of the creative mind of the people there, and of course the beauty,” he said. “And also for other folks to know that there’s more to Africa and there’s more to Ghana than is often portrayed … I like to keep it on me because, again, it grounds me. Too often when I’m wearing everything Western, if you want to call it that, I want to have something that reminds me of those things.”

———

Eleven hours. Eleven hours and 5,260 miles over an expanse of Atlantic ocean. Kobby is 11 years old, and he is leaving Ghana. His mother has been relocated to the U.S. and is taking Kobby and his siblings with her.

He sits in his single seat in the airplane. He is not nervous to fly; they have taken long trips before. But in the back of his mind and in the pit of his stomach, Kobby knew this would be an entirely different experience that he never before could imagine.

“I remember at 11 our parents telling us, ‘Your mom is being posted’ — that’s the language — ‘posted in D.C. as a diplomat,’” Kobby said. “So we were like, ‘OK, what does that mean? I guess we’re going to America.’ So America became this thing, this sort of shadowy notion, until we got here.”

Kobby would enroll in a public school in Maryland with his siblings. Emelia said adjusting to their new life was hard at first, mainly because of the culture shock. People knew little about where she and her brothers came from, having only stereotypes of what they thought Africa was to go on.

From right, Kobby, his father Steven Lartey, his mother Jennifer Lartey, his sister Emelia and his brother Kojo pose for a family photo in Delhi, India.

After Kobby’s freshman year in high school, his mother would finish her duties in the U.S. and would be leaving back to Ghana. But Kobby and his siblings would not go back with her. Instead, they will enroll in boarding school. There are boarding schools in Ghana — ones that were established when missionaries used to travel through the country — yet they decided as a family it would be better for them to remain in the U.S. because they believed there would be better opportunities here. That didn’t make things easier.

“It was tough, it was difficult,” Kobby said of the permanent move. “It was like your whole world was suddenly different.”

———

It is Dec. 1, 2014. The sky is clouded, and the air is cold. A crowd is growing as Kobby stands on the raised platform. Some 200 Ithaca College students walked out of their 1 p.m. classes as agents in a nation-wide protest.

Kobby pauses a moment. The air is heavy with charged energy. This is a crowd that is angry — angry, and passionate.

The crowd grows silent between speakers. In the front, closest to Kobby, a group of black women is huddled together. Maybe they’re friends, maybe they’re not. But they’re crying. Gloved hands wipe the tears from their cheeks and eyes as the cold bites the trails, leaving a mean sting. But they don’t leave. Others have, and as time ticks on, more will. But they don’t.

There is a bitterness that can be felt. A swelling of the heart reflected in every person standing outside that day, who decided to take a stand for something more.

“It basically means being a human being,” Kobby said later. “I don’t think that you’re really fully a human being if you don’t have some kind of connection to something bigger and better than yourself. That can mean someone else, that can mean something else. It’s not really an option. At least for me it’s not really an option.”

It basically means being a human being. I don’t think that you’re really fully a human being if you don’t have some kind of connection to something bigger and better than yourself.

The winter wind whips the air as Kobby raises a single arm to the sky.

———

At Ithaca College, Kobby is minoring in African Diaspora Studies and International Politics. Kobby said the classes he’s taken at the college, both in the Center for the Study of Culture, Race and Ethnicity and in the School of Business, are essential for sparking dialogue about issues of inequality and awareness.

“Classes like that really created the framework and allowed us to have the political, emotional, and I think in many ways spiritual imagination to think of the world as it should be, as opposed to how it exists right now,” Kobby said. “There’s a saying called Sankofa, and it’s to go back and retrieve. That you can’t understand where you are or where you’re going if you can’t understand where you came from: the past.”

Kobby specifically cited the Gender, Race and Economic Power course he took freshman year in the economics department, as well as courses with Sean Eversley Bradwell, assistant professor in the CSCRE, but he has ensured these types of conversations happen outside of the classroom as well. His freshman year, he lived in Terrace 3, which at that time was the housed the Housing Offering a Multicultural Experience program. He is now president of the college’s African Students Association, where he has helped focus the club on tensions and the diaspora between the African continent and the rest of the world globally. Awareness is the goal of the ASA, and a goal of Kobby’s.

From left, Kobby and journalism department Chair Matthew Mogekwu talk casually during The Collective’s Deconstructing Media Tropes of Bodies of Color discussion held Feb. 4 in Williams Hall Room 202.

Matt Mogekwu is the chair of the journalism department and the current faculty adviser for the ASA. He said before he became the faculty adviser of the organization, he would occasionally attend its meetings and follow along with its progress. Being from Nigeria and having been involved in ASA-like groups on other campuses, it was only natural to continue the trend here. From that, he has gotten to know Kobby over the last couple of years.

“He is a very articulate guy,” Mogekwu said. “I used to call him — I still call him — ‘Ambassador Plenipotentiary’ because he has this air about him that gives that impression … he’s very knowledgable about things, around here and about where he comes from, and is always ready to educate people about it.”

———-

Fifteen-year-old Kobby is at a new students ceremony for Choate Rosemary Hall, a private, Connecticut-located boarding school and preparatory academy. As the school’s alma mater plays, he looks back. His aunt is in the crowd. She is crying. She is crying for all the new opportunities he and his siblings will have in the U.S. that they might not have gotten back home. When Kobby thinks back on it, he laughs.

Kobby walks on the 458-acre campus of Choate. Before arriving here, Kobby went to John F. Kennedy High School in Maryland. He now walks the same halls Kennedy once walked before he graduated from Choate in 1935. Kennedy is one of the school’s most notable alumni, along with 11 U.S. ambassadors and at least one Nobel Prize winner.

Choate is marked by its old architecture, giving clues to its age. It was founded in 1890, and the buildings lean heavily toward colonial revival. Red brick walls are accented with white pillars around doorframes and white window trimmings, the insides are a mix of creamy plasters and rich wood paneling.

“I think there was something about Choate, something that Choate made you feel once you entered,” Kobby said. “Mrs. Mitchell, she’s passed away recently, she was like the secretary at the front desk, she made us feel like we belonged. That it was home.”

But his time there was not always easy. As a shy student, Kobby said it was initially difficult for him to open up to people. His very first interaction at Choate was with his headmaster.

“That I made the headmaster laugh was kind of interesting,” Kobby said. “As a shy boy I was like, ‘What? I made him laugh? How did I make him laugh, I’m not funny.’ But again, I was shy, I was a little bit quiet, I was still trying to figure out what it meant to be myself and be by myself.”

But Kobby would find himself in time. After a failed run-in with some sports teams — “I tried out for football. That didn’t work out. I didn’t like it. I was like, ‘Why are people hitting each other? What is this hitting they’re doing?’” — Kobby would find his place in Choate’s Student Government Association, Africa Club and in creating a community service advisory board.

During Kobby’s time there, he would rise to be a prefect during his senior year and would go back as a teaching intern in the summer of 2014. Eera Sharma, the director of summer programs at Choate, said while Kobby was an intern he was able to garner respect from the students, something she said is usually very difficult. Because of the closeness in age between high school students and college students — sometimes as few as four years — it can be hard to be seen as a person of authority and not just a friend. But Kobby didn’t have this problem, easily being able to play both roles.

This may be due to his tendency to see the good in everyone. Eric Stahura, one of Kobby’s teachers and advisers while at Choate, said Kobby was always one for optimism.

“He looked at life with idealized and optimistic lenses. Even when he was 15 years old he wanted to make the world a better place,” Stahura said. “But he was especially going to start with Ghana because there were so many things that needed improvement, and he wanted to do that through government, through political channels.”

At Choate, the curricula follow the Socratic method. Desks are arranged in large circles, and students have discussions — not lectures — with their teachers.

“I remember one moment that really resonated with me was when we read Dr. King’s letter from Birmingham jail, and I was like, ‘That man can write,’” Kobby said. “And he could write because there was a humanity in his voice. There was something coming out of the paper and grabbing you and telling you ‘You need to read this’ and I said ‘I hope one day I can be even half of that.’”

And Dr. King could write because there was a humanity in his voice. There was something coming out of the paper and grabbing you and telling you ‘You need to read this’ and I said ‘I hope one day I can be even half of that.

———

About 40 Ithaca College students gather in Williams Hall Room 202 on Feb. 4. The Collective is holding a talk for its Assata Shakur Series, a discussion series aimed at examining instances of inequality and how some people have been fighting against oppressive systems. The Collective is the name given to a group of students on campus, whose goal is to have meaningful discussions among the college community about systemic violence and institutionalized inequality.

“We didn’t really call ourselves anything, but we wanted to organize some sort of demonstration to kind of relay the things that we were experiencing at home,” Kayiza said. “I think the name The Collective happened because people kept asking, ‘What student org are you with?’ ‘What student org are you with?’ So we just needed a name to the people involved.”

Last semester, these students organized a number of protests and demonstrations on campus to promote awareness of instances of injustice.

“It’s clear to me that they are thinking seriously about a range of political issues and are also interrogating their own politics every step of the way,” Asma Barlas, professor in the CSCRE, said. “I should also say that, in my 23 years at IC, the action last semester was the largest political protest on this campus. I found it simply amazing for that reason alone. I’m also impressed with how clearly the students in The Collective understand the nature of structural oppression.”

Kobby walks into Room 202, briefly glancing around before taking a seat at the far end near the wall. As he takes off his scarf, his usual tan infinity scarf, he says hello to individual people he knows in the crowd — which happens to be the majority of them. But soon it’s time to be serious. He crosses a leg over his knee and places his hand under his chin, listening as Kayiza begins to talk about black representation in the news media.

Kobby took part in the group’s previous demonstrations, and has kept himself in the loop this semester. He will always be engaged in discussions about inequality, whether on a global scale or specifically looking at the U.S. He has no other option.

“I have no choice but to be engaged: I’m an African living in America,” Kobby said. “There’s something about that experience that pushes you to be engaged, and my folks always taught me — my grandpa and my mom — you have to really constantly understand the world while seeking to better yourself. My interest started off by what can I do to better myself, and how does that transfer to pushing for something or demanding for something.”

But it is not only Kobby pushing for long overdue answers, pushing for the dialogue that has spent so long being suppressed to come forward among the campus community. It is every member of The Collective. Every student who participated in a protest. Every student who made their voice heard. Every student who stood up.

“One thing I hope people take away from these experiences these last two semesters is that anyone can create the change that they want to see on this campus,” Kayiza said. “The Collective is a body of people that brings so many different things to the table, and I think that’s why we’ve operated the way that we’ve done, and there’s no leadership hierarchy, and it’s not about who’s in power and who’s visible, it’s just about a bunch of people who really care about an issue enough to say something about it.”

———

About 200 Ithaca College students walked out of their 1 p.m. classes as part of the Hands Up Walk Out demonstration Dec. 1, 2014. This was a nation-wide protest against instances of inequality and police brutality.

The winter wind whips the air as Kobby raises a single arm to the sky.

“Amaaaaaaaandla!” he cries out, into the microphone.

“Aweeeeeeethu!” 200 Ithaca College students and faculty yell back at him.

“You can do it louder than that,” Kobby says to them. “If we’re loud enough, maybe the sun will come out.” The crowd laughs lightly. The sky is dark and crisp and shows no sign of changing. Kobby presses on. “Come on. I want them to hear us all the way across campus. All the way in Terrace Dining Hall, people need to know that we are here. AMAAAAAAAAAAAAAANDLA!”

“AWEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEETHU!” The students are screaming it now, and the sound reverberates through the open quad.

Amandla, Awethu. Steeped in a history of fighting oppression, the phrase means “Power to the people” in Zulu.

Amandla, Awethu. The phrase is still used today as a rallying cry for those fighting against oppression. To fight against cultures of silence. Two-hundred Ithaca College students scream the phrase at the top of their lungs, and the clouds suddenly begin to break. First one ray, then two. A patch of sunlight streaks through the sky and onto the crowd.

The students had had enough of talking, so something was started that day. A call to action. A call for change. Two-hundred Ithaca College students came together for something more than themselves, their shadows lost and unified into one. They are a moving force — a force of voices. Voices that will not be silenced.

Kobby looks up. He smiles.

“See, I told you we could make the sun come out.”