Editor’s Note: This is a guest commentary. The opinions do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial board.

If you caught me about six years ago, I would fit the bill of a crazed environmentalist who took pride in judging and guilting people into protecting the environment. I never printed anything because I felt guilty about killing trees, I did not use plastic straws and I judged people who had cars. Although I sometimes think it was my adolescent naiveté, I also know it was because I felt so very responsible for ensuring that the wrongs in the world were righted. What I failed to grasp is that every person and phenomenon is connected by an intricate network of systems.

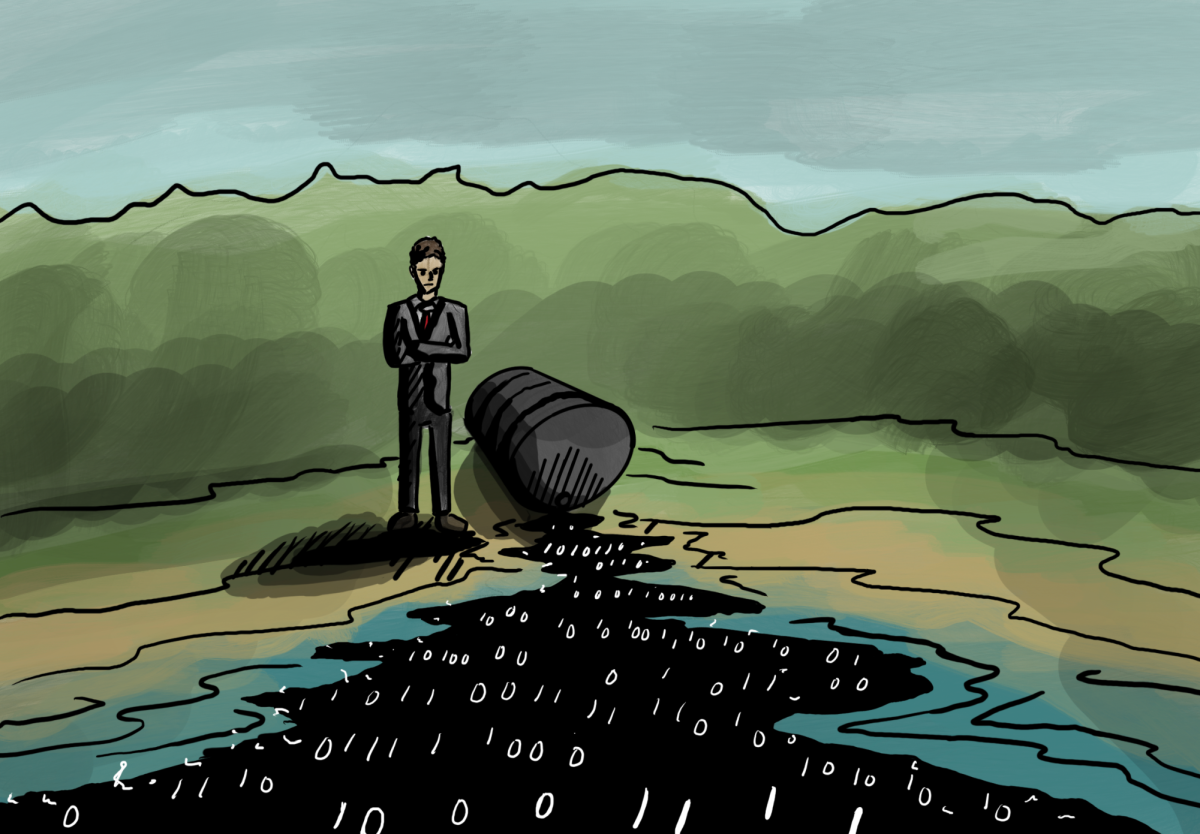

Everything you could imagine falls under this ‘system,’ ranging from capitalist society to the real estate market to coffee plantations. These individual processes come together to wreak havoc on not only the environment, but also the people whom it was meant to serve. I have had to develop the awareness of the connectedness of our political, social, economic and environmental lives to understand how I can be a better environmentalist.

Through college, I have been able to understand how modern society impacts the environment by uncovering pieces of the puzzle along the way. In an environmental policy class I took, each student picked a country to study. My choice was to study Bhutan — a small landlocked country to the north of India, situated in the majestic Himalayan range. What people usually know about Bhutan is the fact that they don’t measure the development of the country by GDP, but by their Gross Happiness Index. They are also often recognized for being one of the only carbon-negative countries in the world today.

As I studied Bhutan, I started to learn about the environmental policies they have in place (I’ll spare you from the details, you do not need to see me go into a nerdy ramble about zoning and forest harvest regulation.) In a study done by Rinzin et al., people had a positive view toward forest protection even when they were getting the short end of the stick. One of the biggest issues troubling people in Bhutan today is human-wildlife conflict. This occurs when forests — protected resources — start to encroach on settlements and wildlife like snow leopards and bears destroy farmland. I started to question how you can be satisfied with something while knowing that it is negatively impacting your ability to earn money, collect firewood, harvest food and protect yourself against wild animals? It seemed bizarre and unlikely.

Taking what I learned from a class on Buddhism, I started to build connections with the particular type of Buddhism practiced in Bhutan and how it forms views about nature conservation in Bhutan. Part of what I discovered was the Buddhist doctrine of ‘Pratītyasamutpāda’ that postulates the interconnectedness of the universe. This implies that the environment is not an external resource but a part of our lives, who we are and how we find purpose. Therefore, even at the expense of oneself, many Bhutanese support the conservation of nature because they believe that conserving the environment is crucial for their wellbeing. This is a clear example of nature impacted by cultural beliefs and behaviors.

An example of environmental issues overlapping with race and wealth is the case of Hurricane Katrina, where low–income housing and predominantly Black neighborhoods were located below sea level, disproportionately impacting people in those communities. The apathy of the George W. Bush administration showed as African-American communities did not receive the aid they needed to rebuild. This disaster has caused African-American communities to leave New Orleans, a primarily Black city. People living closest to spaces of vulnerability are typically low-income housing, a present day manifestation of historical redlining. Although triggered by environmental factors, this human-made disaster impacts are intermingled with the sociopolitical implications of who is most at risk, and who has access to government support.

Although proper waste disposal, reducing what you buy from stores and using public transportation helps, these actions do not address the systems of which they are simply symptoms. I have realized that what I can do as a woman of color in environmental science is to encourage an interdisciplinary view of the subject. We need to look at our environmental crisis as a crisis involving people of color, low-income groups, women and LGBTQ+ communities. Only if everyone comes to the table together to fix the systemic issues that have gone unchecked for years can we be equipped to start a fight against climate change.

Nandini Agarwal (she/they) is a junior environmental studies major. Contact them at [email protected].