Since before COVID-19, Ithaca College has had a larger faculty and staff salary gap when wages are compared to other higher education institutions. During the pandemic, this wage gap for faculty and staff widened as a result of a freeze on inflation-adjusted wages, according to David Gondek, associate professor in the Department of Biology and chair of the Faculty Council.

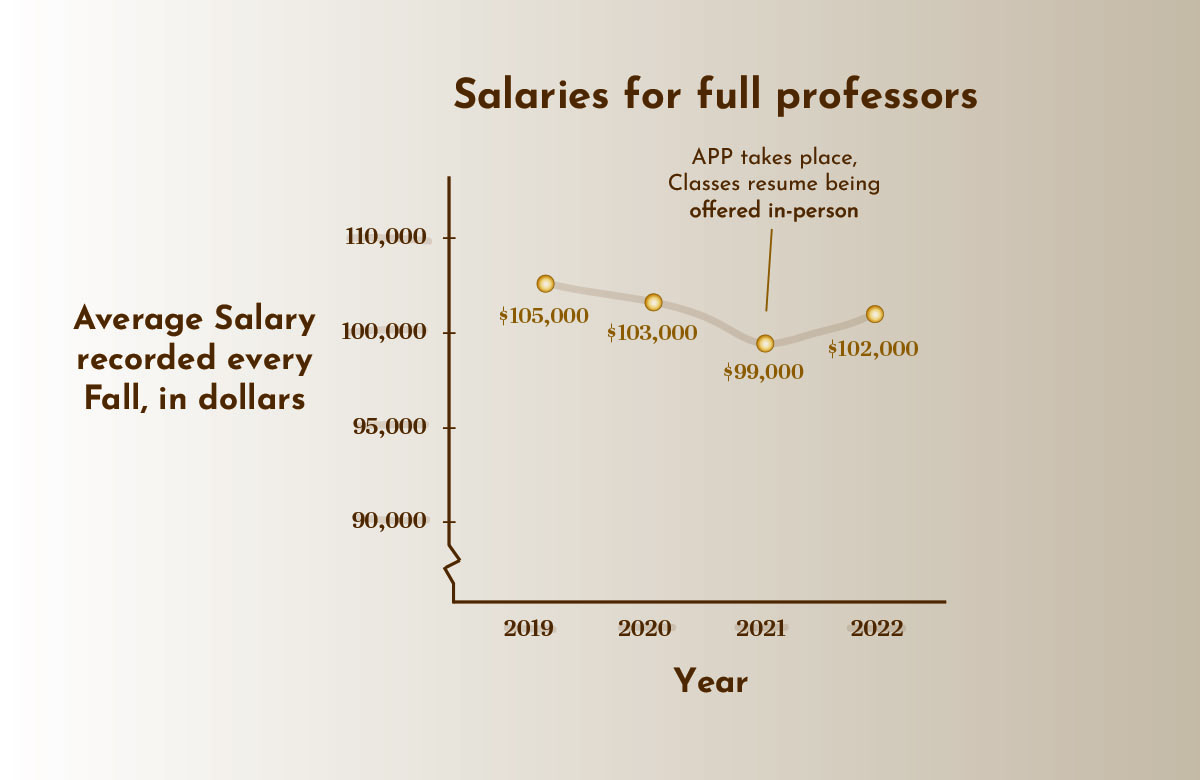

Faculty and staff at the college annually receive a 2–3% salary increase to account for inflation every year July 1. The freeze on inflation-adjusted wages was a cost-saving measure the college took during the pandemic between July 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021. The Academic Program Prioritization (APP) was sped up as another cost-saving measure during the pandemic.

As the college seeks to get the 2024–25 fiscal year budget approved by the Board of Trustees on May 17, Melanie Stein, provost and senior vice president for academic affairs, hopes to set aside funds in the budget to decrease the gap. At the time of publication, Stein could not say the exact number of the funds because the budget has not been approved. Stein said the plan should be in effect for five to six years to make a difference in the gap.

Faculty salary gap

Kirra Franzese, associate vice president and chief human resources officer, said the freeze on inflation-adjusted wages ended in 2021. Stein said the freeze on inflation-adjusted wages was not an isolated phenomenon and was something colleges across the nation experienced because of low enrollment.

Gondek said that since the freeze on inflation-adjusted wages in 2020 and 2021, he thinks that the college has not returned to pre-pandemic levels of salaries for some positions.

Gondek said the college also stopped contributing to retirement funds for all employees in 2020. Both the employee and the employer pay into the retirement plan. The college is on the path of restoring full retirement contributions, according to Tim Downs, vice president for Finance and Administration and chief financial officer.

Stein said the college would not want to decrease the size of its faculty any further to save extra costs when the college is expecting enrollment to begin increasing.

“We’re not a supermarket, where you can just hire more checkout people when you need them,” Stein said. “And we’re talking about really highly skilled employees, for instance. Faculty … are typically here with us for many years. We wouldn’t want to suddenly artificially reduce our faculty because our enrollments are temporarily depressed … when we expect them to come right up.”

Why enrollment matters

The college is a tuition-dependendent institution. When enrollment is high, there is more revenue for the college. However, when enrollment is low, the college receives less revenue. This means that the more money the college has, the more faculty and staff can be employed at the college.

In the 2019–20 academic year, total student enrollment at the college was 6,266, and during the pandemic in the 2020–21 academic year, total enrollment was at 5,354. During the 2021–22 academic year, total student enrollment was 5,239 and during the 2022–23 academic year, total enrollment was at 5,054. Stein said enrollment is predicted to stabilize after the decrease the college observed during and after the pandemic.

Marist College is comparable to Ithaca College and known as a peer institution. Marist’s average annual tuition is $46,920 while Ithaca College’s is $53,540.

In 2023, the average salary for a full professor at Marist was $129,700, an associate’s salary was $108,200 and an assistant professor’s was $92,400, according to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP). In comparison, the average salaries for a full professor at Ithaca College was $105,000 in 2023, an associate professor’s was $88,700 and an assistant professor’s was $69,300.

Once the freeze on inflation-adjusted wages took place during the pandemic, full professors’ salaries at Ithaca College decreased by $6,400, associate professors’ decreased by $4,300 and assistant professors’ salaries increased by $300 from 2021 to 2023.

“I see it as taking the pathway where we’re slowly inching our way back up,” Gondek said. “So as we are rebounding with student numbers, we’re also prioritizing across the institution and faculty salaries is one of those priorities.”

Gondek said that despite the salary gap, some faculty decide to work at the college because of non-monetary benefits like the quality of life in the Ithaca area. He said the college ranks as an “employer of choice,” an institution where people want to work.

“Salary, retirement and benefits tend to be the things that people will look at when they’re trying to say, ‘I would prefer to work in Ithaca than another institution,” Gondek said. “What we’re trying to do is that although we might not be paying at the top end of salaries, there are other really good reasons to live in the Ithaca area.”

However, 70% of faculty reported in the Campus Climate survey that they had considered leaving the college. 67% of faculty reported that low salary was a reason they considered leaving.

Amber Lia-Kloppel is a lecturer in the Department of Art, Art History and Architecture, and is a steward for the Ithaca College Contingent Faculty Union. Lia-Kloppel said contingent faculty contract end June 30, so the union is at the bargaining table with the college to negotiate a new contract. She said the contract should include an increase in salary to help defer the impacts of the pandemic.

“Many of our members taught through the pandemic, online, hybrid and then in person,” Lia-Kloppel said. “They were incredibly dedicated to the students and to the institution during an unprecedentedly challenging time. And we also went through record inflation … so we were essentially being paid less while we went through the pandemic.”

The average rate of inflation in the U.S. between 2022 and 2024 was about 5.6%. In March 2024, the inflation rate was 3.5% as compared to March 2023, according to Statista.

“We’re actively trying to get a much greater wage increase and we appreciate Ithaca College’s plan towards greater diversity and equity and inclusion,” Lia-Kloppel said. “And we believe that fair pay, equal pay for equal work, is absolutely a part of that ethos.”

Staff wage gap

While there is also a gap in staff wages, Franzese said this gap can be attributed to different factors than the faculty salary gap. She said factors included frozen inflation-adjusted salaries and that the college ranges from 10–15% of the market median.

Franzese said that even if the college froze inflation-adjusted salaries and wages now, like it did during the pandemic, the college will still have the funding for an annual increment for future years.

“I would say on the faculty side, they face the same challenges that we face on the staff side with increments for a couple of years as well as just trying to maintain market position in the inflationary environment that we’re in,” Franzese said.

Franzese said the college has some staff positions that are paid within 10% below the market median and some positions that are paid above the market median. The market median is a figure that represents the middle point of all salaries and wages in a specific career or industry. According to Statista, the median income in New York state was $75,910 in 2022 and $72,920 in 2021.

Provost’s plan to shorten the gap

Gondek said that because of the revolving door of provosts at the college, a provost has not had enough time to develop a plan to shorten the faculty salary gap. Benjamin Rifkin served as the college’s provost in 2015 but stepped down in 2016. Linda Petrosino then served as interim provost from 2016–2018 and President La Jerne Cornish was the college’s provost from 2018–2022.

“Any priority that a provost puts in place, are they going to be here long enough to actually see that all the way through?” Gondek said.

Stein said the plan’s funds will appear in the 2024–25 fiscal year budget, as long as the BoT approves the budget. She said the funds for the plan to reduce the faculty salary gap will be split in half. Half of the funds will go directly to all faculty of the college and will be distributed by the Office of the Provost. The other half will be distributed by the deans of each school to give to faculty members on a custom scale, meaning that different faculty will receive different amounts from their dean. She said every continuing faculty member will get some of the allocated budget.

“Every continuing full-time faculty member, those are the folks that this strategy applies to, will get something,” Stein said. “Everybody will get something, but how much they get depends on [what] their rank is.”

Stein said the deans of each school at the college must have this responsibility to share funds with faculty members who they know better than the college’s administration does.

“They’re going to know stuff — like maybe they have six departments, and they happen to know that one of them is severely under market,” Stein said. “So they might divert some of the funding that I’m allowing them license to distribute, they might put it in that department or they might have issues where internal inequity has developed.”

Stein said the plan will need to be continued over the course of five to six years to make a change in the gap and be included in the budget each year.

“That is definitely my plan and my intent to continue this because it’s a sizable problem,” Stein said. “We measure to see how far off we are. And then we realized this is not something that you can just fix in one year. This is something that’s going to take a multi-year approach.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated the SEIU contract ends July 30. The contract ends June 30.

Julianne Hunter • May 3, 2024 at 5:09 pm

To be clear, this article was amended by a writer AFTER the comment by Amber was posted a few hours ago. I am disappointed that this was not made clear by the author, nor the Ithacan, and does not appear to be disclosed on this site.

Amber Lia-Kloppel • May 3, 2024 at 12:28 pm

I’m writing this comment to complain that I was misquoted multiple times in this article by the author, and that upon my request these misquotes were only partially amended. I can’t help but feel that my voice as a member of the contingent faculty was taken less seriously and given less time and consideration than other voices represented here.

For this reason, I’m compelled to write here what I actually said during the interview, according to the notes I read from:

First to correct what was inaccurately summarized in the article: The contingent faculty contract ends June 30th, and the union is trying to negotiate a new contract. The contract we’re trying to negotiate has increases in wages to help defer the impact of the pandemic.

The implication that these increases are uncontested by the college was false and not my own.

And second, to correct what was misquoted: We appreciate Ithaca College’s plan towards greater diversity, equity, and inclusion, and we believe that fair pay (equal pay for equal work) is absolutely a part of that ethos.

Sincerely,

Amber Lia-Kloppel

Union Steward and Lecturer in the

Department of Art, Art History and Architecture Ithaca College