March 14, 2015:

The baseball team is closing out the final frames of a seven-game, Southern California road trip over spring break. The weather is almost summer-like, a tease for the team, which will return to sub-freezing Ithaca the next day. But for now, it’s perfect baseball weather.

As he has done so many times before, head coach George Valesente watches from the dugout as his team looks to finish its annual trip on a high note. It’s been a tough week for the Blue and Gold, who have clinched just one victory — an 11–9 extra-innings thriller against Occidental College — thus far. But now, with a 2–0 lead in the top of the ninth against Spalding University, the Bombers are trying to get back to South Hill with another win under their belts.

It’s just another regular season game for Valesente’s team, but then again, it’s not, and the players know it. The 70-year-old head coach, who is in his 37th year, has been coaching since before any of his current players were born. The 999 games that the Bombers have won since 1979 have all been under Valesente’s watchful eye. But this is the big one. [block] Winning 1,000 games at a single institution is something few coaches can lay claim to. [/block]

“We wanted to get it done out there for him,” senior catcher Cooper Belyea said. “It was definitely in our minds.”

Senior Andrew Sanders is on the mound for the Bombers. There are two outs in the inning, and Sanders is pitching to the Golden Eagles’ designated hitter after retiring the first two batters of the inning and having a runner reach on an error.

Now, Sanders eyes the base runner — who is dancing teasingly off first base — over his left shoulder. Ensuring that the runner will not attempt to steal, Sanders refocuses on the batter. He just needs one out. Throwing from the stretch, Sanders delivers what he hopes will be the final pitch of the game…

One month earlier:

Valesente leans back in the stiff, white chair near the entrance of the Athletics and Events Center and looks out at the falling snow that is coating Higgins Stadium and the parking lot outside. The powdery white is accumulating quickly and shows no sign of stopping. He dreams of spring.

His team has just finished a two-hour practice in the warm confines of the A&E Center. Several players have stayed behind to take extra batting practice in the netted cages by the track, and the ting of aluminum bats finding their mark reverberates across the building. But the noise of ball meeting bat — normally one of the purest sounds in the sport, in all of sport — is tainted. It’s the echoes. This game was not meant to be played indoors.

Valesente knows this all too well. Forty-three years of coaching at four different schools in New York have brought too many long winters and short springs. But the springs are always worth it. When the well-trimmed grass on the diamond across campus finally makes its appearance from under the snowdrifts, and the red dirt of the infield loosens enough to slide on, that’s when the season can finally begin. That’s when the fun can finally begin.

But for now, it’s still winter, and the team won’t taste spring on South Hill for at least two long months. As Valesente watches the flurry outside, he reflects back on the 37 years he has held the reins of the program. To him, the wins are just a number, a quantifiable statistic that looks impressive on a sheet of paper. The nearly four decades he has been the head coach have been so much more.

For a moment, he is lost in thought.

“It’s been the best thing that could happen,” he said. “I don’t know if there’s any other person on the planet who could have had it any better than I have.”

Summer 1952:

Established in 1831, the small town of Seneca Falls, New York, was a bustling industrial hub due to the river that runs through its heart. Its 19th-century residents, however, were interested in more than just factories. Home to the first Convention on Women’s Rights in 1848, Seneca Falls was well-known for its support on reform issues such as slavery abolition, women’s suffrage and temperance.

This was where Robert and Virginia Valesente chose to raise their children. As Valesente and his brother, Bob, grew up, the thriving community featured a population of about 7,000, including plenty of young athletes for the brothers to compete against.

Valesente is 7 years old and is, as usual, tagging along after Bob. The boys sprint out the front door of their small, two-story, Victorian-style house. They pause only to grab a broom and a whiffle ball as they make their swift exit.

Outside, the summer sun streams down on the grassy yard adjacent to the Valesente household. The brothers take turns pitching to each other, using the broom as a bat. Walnut Street is constantly abuzz with the sound of children running through the streets, and the Valesente brothers are no exception.

“The natural tendency back then was everyone was out playing,” Valesente said.

Even though Bob is four years older than Valesente, and Valesente considers his brother one of his best friends, the two constantly compete against each other. Valesente latches onto the idea of competition, and it quickly becomes a staple in his personality.

“He was very talented, so we did a lot of things together,” Bob said. “If I had something going on and he wanted to get involved, he got involved.”

Because Seneca Falls did not have an organized Little League until Valesente was 9, it was Robert who served as his first coach. A construction foreman, Robert had also grown up playing sports and was a major influence in both boys’ lives as they continued to progress in their athletic careers.

“He was a motivating force,” Bob said. “He never pushed it on us, but he was a guy that was always interested. There were a lot of great moments there that we shared because of that.”

There were many great moments with his father, but Valesente also was very close to Bob as he grew up. Two years later, Valesente is once again following his brother. The now-13-year-old Bob is headed across the river to play sandlot baseball with his friends, and his younger brother desperately wants to come.

At the insistence of his parents, Bob allows Valesente to follow him to the field on the other side of the river. The boys hop onto their bikes, baseball gloves hanging from their handlebars, and fly down the streets.

To Valesente’s dismay, Bob and his friends don’t need an extra player when they arrive, and as the youngest one there, he is automatically excluded.

Dejectedly, he sits on a log off to the side of the field, waiting for one of the older boys to leave. Finally, one does.

“We need Valesente!” one of the players yells over.

Valesente perks up immediately and enters the game, excited for the opportunity to prove himself to his brother and his older friends.

“My brother was my idol, I idolized him,” Valesente said. “They would tell me where to go and when to bat and what to play and I said, ‘yes, yes,’ and just did it.”

After returning home, Valesente watches the Yankees play on his parents’ television. A youthful center fielder named Mickey Mantle appears on the black-and-white screen. The young Valesente stares at the grainy picture in awe, memorizing Mantle’s moves so that he can imitate them on the sandlot the next day. [block] At that point, Valesente doesn’t know that a lifelong passion had just planted itself into his mind. [/block]

Spring 1963:

Valesente leaves his Ithaca College dorm room on Quarry Street — converted from an old hospital building for the college’s use — and walks through downtown Ithaca toward the Seneca Street Gym for his first class of the day.

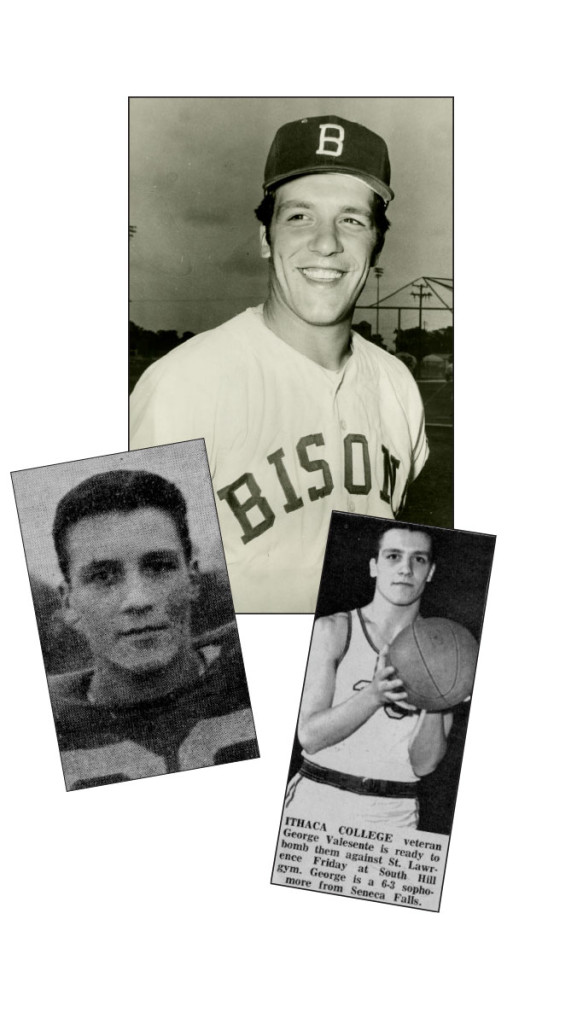

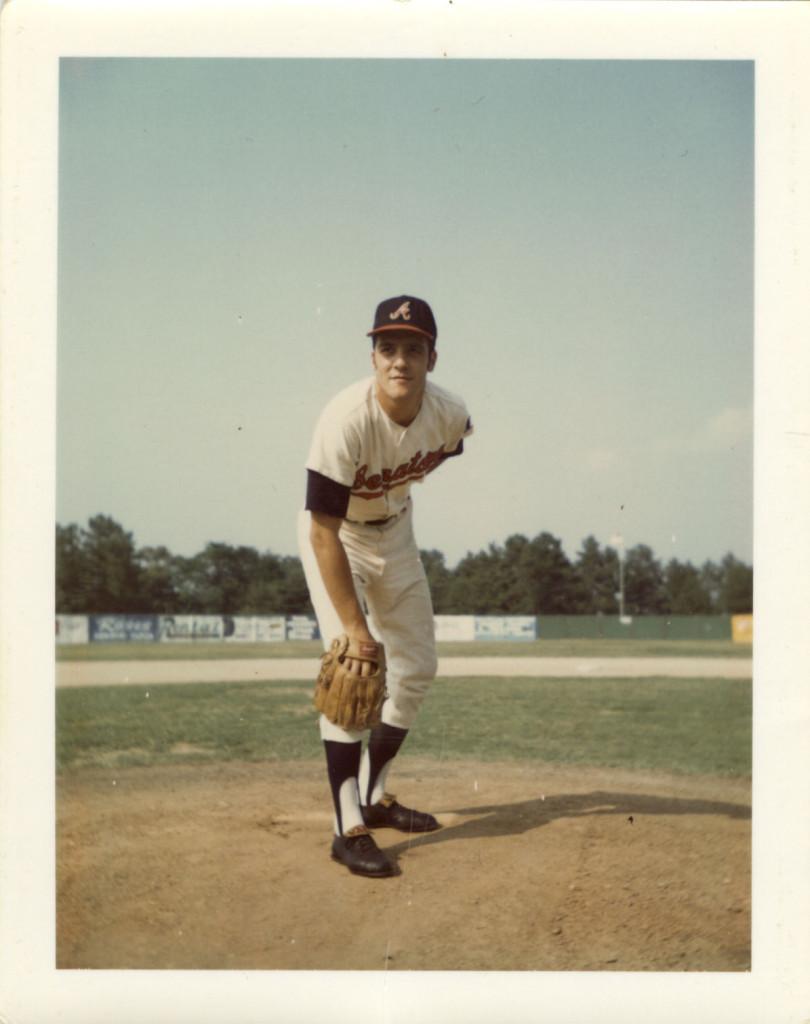

Now 18 years old and a freshman at the college, Valesente finds himself once again following in his brother’s footsteps. While Valesente was starring in baseball, football and basketball during his high school years at Mynderse Academy in Seneca Falls, Bob was an All-American college baseball player and co-captain of the 1962 Ithaca College team that became the smallest school to ever appear in the Division I College World Series. The Bombers would later move to Division III in the 1970s, after both Valesente brothers had graduated.

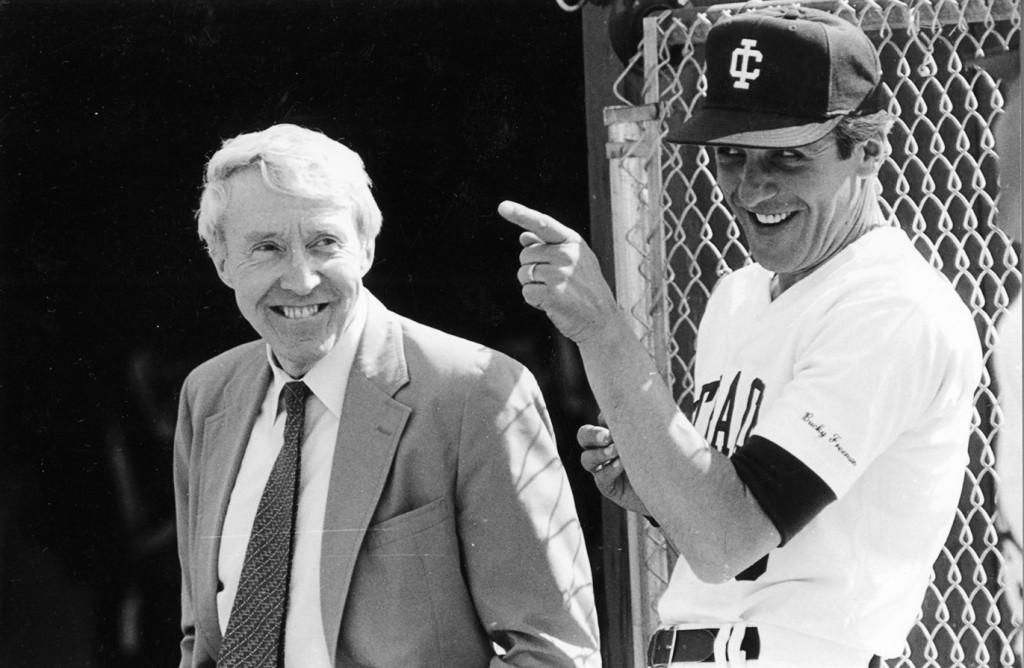

In his final year at Mynderse, Valesente watched on television as his brother’s team fell to the University of Texas, 4–3, and was eliminated from the tournament. That season, Bob’s senior year, was also the inaugural season of the diamond that, some five decades later, would be christened the George Valesente Diamond. Valesente knew Ithaca College was the place he would end up, and he often made the hour-long drive with his father to watch his brother play for legendary head coach Bucky Freeman, who would soon become a mentor to Valesente.

As the college developed on South Hill — when he was a freshman, only two buildings stood on campus — so did Valesente’s character. During his four years, glimpses of the coach he will later become began to shine through, particularly on the baseball team and namely through his trademark competitiveness.

During his three years on varsity baseball, Valesente’s teams won 39 games, and for Valesente, it was those 39 victories that laid the foundation for a lifetime of winning. But he didn’t know that just yet.

“I never really prepared my life very well,” he said. “I never sat down when I was 17, 18, 22 and decided that I want to coach. I didn’t know really what the hell I wanted to do.”

Summer 1972:

It was coaching that eventually called to Valesente, but it didn’t come immediately, and it certainly wouldn’t have happened without his connection to the college.

A 27-year-old Valesente is surrounded by family at a wedding. His playing career over after a short stint in the minors — he made it as far as the Triple-A Buffalo Bisons before retiring for good — Valesente finds himself unemployed.

It is an uncharacteristically cold day, the temperatures falling to the low 60s, contradicting the mid-August heat wave typical of upstate New York. Valesente is enjoying the wedding with his brother when Bob suddenly gets a phone call. On the other end of the line is Bob Christina ’62, who had co-captained the 1962 World Series team with Bob. Christina had been the head baseball coach at SUNY Brockport, but was stepping down. Looking for a recommendation for the position, Christina seeks advice from Bob, one of his closest friends and teammates at the college.

“I said, ‘I know just the guy for you, he’d be great,’” Bob said. “And he said, ‘Who’s that?’ and I said, ‘My brother George.’”

It is at that family wedding where Valesente gets his first big break. Christina takes Bob’s word and sets up an interview for Valesente for Monday morning, fewer than 48 hours after the wedding. Valesente returns home and prepares the best he can in the hours he has before his interview.

He arrives in Brockport on Aug. 17. Classes begin in two weeks and the baseball program needs a quick hire. At Christina’s urging, the Golden Eagles appoint the young and inexperienced former Ithaca College student, fresh from completing his master’s degree and several graduate assistantships in various sports at the college.

“I pushed real hard on my end at Brockport for them to hire him,” Christina said. “I said, ‘Look, I know this guy and I’ve seen him play. I think he can do this job. He’s a good person.’ The rest is history.”

After his hiring, Valesente packs up his belongings and drives to Rochester, New York, near Brockport, where he lives temporarily with one of his old college roommates and best friends, Wayne Lyke, who works for St. Joseph’s Villa, a home for mentally disturbed and neglected children. The two meet for lunch one day, and Valesente is introduced to his secretary, Dianne. He couldn’t have possibly known then that this acquaintance would be the woman with whom he would spend the rest of his life. After several years of Valesente returning to Rochester in the summers to teach recreational activities at St. Joseph’s, the two would eventually begin dating.

But after that first, brief meeting, the two part, at least for now. Valesente needs to get ready for his new coaching job.

Two weeks later, as the uncharacteristically cold August turns into a warmer September, Valesente runs his first-ever tryout.

The school is still constructing its baseball facility, so Valesente moves the tryout to the nearby Brockport High School softball field. Over 100 student-athletes show up. Valesente isn’t ready for the sheer size of the tryout, and on that day, learns the importance of preparation.

“I absolutely had the worst tryout ever in possibly the history of tryouts because I wasn’t prepared,” Valesente said.

It is a lesson that sticks with him even now, four decades later, as he runs the Ithaca College baseball team’s practices, constantly carrying around a clipboard that holds schedules and other notes. They keep him prepared. They keep him successful.

Fall 1976:

After leading the baseball programs at Brockport and SUNY New Paltz for two years each, Valesente finds himself coaching both baseball and soccer at SUNY Maritime, a quasi-military maritime institute.

The school’s small size and the athletic department’s budget present one of the greatest challenges to Valesente’s coaching career yet. While coaching baseball in the spring, Valesente finds there isn’t anyone to maintain the diamond. He often finds himself out on the field hours before game time, carefully dragging and lining the dirt just so his team can play its game that day. It is this dedication that, four decades later, is still evident in the way he leads Ithaca College’s program. While nearly everything else in the program changes, Valesente is a constant.

Following his second year at SUNY Maritime, Valesente hears of another job opportunity. Carp Wood, who had been coaching the baseball program at Ithaca College since Valesente’s senior year, is stepping down. Valesente jumps at the opportunity, interviews and gets hired. He quits his job at SUNY Maritime, makes the four-hour drive back from the city into upstate New York, and prepares for his newest job.

“I really paid my dues before I came back here,” he said. “I had three great experiences, they were valuable experiences.”

[block] But now, Valesente is finally coming home. [/block]

Summer 1978:

Valesente drives up toward South Hill for his first day on the job. It is a hot August day, and sun streams through the dusty windshield into his old car. After his brief period of unemployment, he is almost completely broke, but he doesn’t care. After paying his dues, at 33-years-old he is finally arriving at the place he wants to be.

As he drives, Valesente struggles with his feelings, fumbling to regain control over his emotion. It is surreal for him, difficult to grasp that he is returning to the program, to lead the program, that gave him so much as a student and an athlete. Nerves knot his stomach and muddle his mind.

The pressure is on. He knows he is next in what has been a long line of iconic coaches. He is replacing Wood, his former coach who led his teams to three World Series appearances in his 12 years at the program’s helm. Before him, Freeman, who, 10 years earlier, had the field named after him following a career in which he spent more than three decades expertly crafting the program, which hasn’t posted a losing record since 1935.

“It was hard to understand that I was going to be the head coach at Ithaca College, replacing an icon that I had looked up to so much and here it was, it was me, and I was nervous,” Valesente said. “I didn’t want to be responsible for its demise.”

As Valesente drives, he reflects upon the long road that led him to this point. The days spent with his brother in their backyard, broom in hand, waiting for Bob to pitch him a whiffle ball. The uphill treks from downtown Ithaca to South Hill to get to baseball practice on time every day. The long, hot afternoons spent dragging the field at SUNY Maritime just so his team would have the opportunity to play that day. All of these moments, all of these experiences, have led to this.

“The pressure was on me to continue to do well in my own mind and work hard,” he said. “I’ll never forget that day.”

Summer 1980:

The stage is set for Valesente. Now 35 years old, he is in his second year as head coach and has led his Bombers to the Division III World Series Championship game in dramatic fashion. After dropping the first game of the double-elimination tournament to Upsala College, Valesente’s team won two in a row, setting up a must-win doubleheader against host and No.1–ranked Marietta College.

It has not been an easy two years for Valesente, however. His team, used to a different coaching style when Valesente took over the program, had slowly adjusted to Valesente, and likewise, he had adjusted to them. But they were talented. Talented enough to lead Division III in both earned run and batting average. Talented enough to make it to the final day of the national tournament.

“They needed some leadership, which Coach Val gave them,” assistant coach Frank Fazio, who was in his first year on Valesente’s staff, said. Thirty-five years later, Fazio still serves as Valesente’s right-hand man. “They really bought into it.”

Six-thousand people, most of whom cheer loudly for Marietta, fill the bleachers behind home plate and down the base lines. Valesente finds himself in an unfamiliar situation.

“We didn’t know what we were doing, we were just there and didn’t know what to expect,” he said.

Dianne paces nervously in the stands as the Bombers fall behind to Marietta, 4–1, in the first game. The two had been long-distance dating — him regularly driving to Rochester and her spending her weekends in Ithaca — for about a year. Soon after the 1980 season, they would be married.

“He always said that I proposed to him, but it’s not true,” Dianne later joked. “I think it was a mutual thing.”

Valesente is quick to say that now, even 34 years into marriage and with two grown children, he and his wife never have had an argument. He smiles when asked about her; she’s been supporting his career for nearly its entirety, including during the 1980 World Series championship, which she said was one of the most emotional days of her life.

It’s emotional for Valesente, too, who was nervous throughout the game and couldn’t shake the feeling of intimidation.

“What it was was a new experience,” he said. “Never having been there before, not quite knowing what to expect.”

He chooses to go with standout freshman pitcher Dave Axenfield ’83, to shut out the Pioneers in the later innings. His decision pays off, as his team climbs back into the game by scoring two runs.

“They needed some leadership, which Coach Val gave them.” [citation] — Frank Fazio [/citation]

“Dave pitched the greatest outs I’ve ever seen,” captain John Nicolo ’80 said. “Bases-loaded and he struck out the side.”

An eighth-inning, two-run home run from senior Ted French ’80 clinched the game for the Blue and Gold. They were just one win away from a national championship.

“In that second game, there was no way we were going to lose,” Nicolo said.

Rejuvenated from its unprecedented comeback, Valesente watches from the dugout as his team’s bats come alive in the second game. Nicolo goes 5-for-6 en route to series MVP honors, and his team upsets Marietta 12–5. Valesente can hardly believe it. As his players mob on the field following the final out, he and Fazio find themselves just as excited.

“We were acting somewhat like kids because it was something we were striving for and we accomplished it,” Fazio said.

There would be parties later, congratulations and ceremonies and celebrations. Valesente knows all of this but focuses on savoring the championship — his first championship. After years of seeking a national title, the ultimate goal for any athlete or coach, he finally has it. But this is just his second year with the program. He knows that he’s not even close to being done.

Winter 2015:

Valesente walks across the rubberized, synthetic gray surface of the Athletics and Events Center, watching his players as they practice. They have split into three groups today: infielders, outfielders and pitchers. While his assistant coaches primarily stay with one of the groups, Valesente oversees the entire practice.

As he walks, he exchanges dialogue with the players he passes. Some he jokes with, others he offers bits of advice. He can be both the loudest person at practice and the quietest, as he often sits back and observes.

Walking through the end of his team’s practice, he encounters a middle infielder taking practice cuts outside of the batting cages. Valesente watches him for a moment, analyzing his swing.

“You gotta smile more, I never see you smile,” he finally says, the edges of his brown eyes crinkling into a soft smile. For a moment, you can see the joy of a child who grew up on a sandlot baseball field. “When you get to my age, then you can be serious.”

It is interactions like these that show that Valesente is not just a coach. [block] He is more than that. He is a mentor, a teacher, a parental figure and a leader. He cares about his players more deeply than just the surface-level coach-player relationships. For many, like Nicolo, he serves as one of the most important people in their collegiate careers, in their entire lives. [/block]

Now 57 years old, Nicolo is a Massachusetts high school teacher and former football coach. Even nearly 40 years after his team helped Valesente win his first national championship, the two remain extremely close, occasionally vacationing together, most recently a trip to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, last year. But more importantly, Valesente has been a fatherly outlet for Nicolo in the years since he has left the college. Nicolo said he often calls Valesente for advice, be it coaching or otherwise.

“He’s like my father, best friend,” Nicolo said. “He always told me just to hang in there and do the best I can. I didn’t have the [coaching] success he did, but the one thing I always took from him is to treat people the way you want to be treated.”

For others still, he acts as a connection to the college, even for his current players, such as sophomore Logan Barer. When Barer took a semester off for personal reasons in Fall 2014, Valesente was the one who helped him get back to Ithaca.

“He was one of the people who reassured me that Ithaca wants me to come back, because I know that Ithaca, the college itself, doesn’t care as much if I don’t come back. I’m just another student,” Barer said. “But to Val, it makes a big difference to him, because I’m part of the team.”

Now pitching for the 2015 team, Barer found his way back to the college, just as Valesente did so many years ago.

Valesente’s nearly four decades at the college have brought with them numerous awards and accolades, most notably inductions into the New York State Baseball Hall of Fame — in the same class as the likes of Vin Scully and Bud Selig — and the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame. In addition, Valesente has led the Bombers to 10 World Series appearances, including his second national championship in 1988. In his 37 years at the college, Valesente has posted 37 winning seasons.

However, if you ask Valesente about it, the accolades mean nothing. What matters to him are the connections. Connections such as Nicolo, connections such as Barer, that allow him to help his players, both current and past, on a deeper level than just their pitching mechanics or batting stance. He and Dianne receive countless Christmas cards, wedding invitations and baby announcements from former players. Dianne even remembers a time when Valesente — who she said is known to be a matchmaker of sorts, in his office in Ceracche Center — set one of his players up with a female student who was working in Ceracche for Valesente at the time. They ended up getting married.

“We were one of the first people to know about it,” Dianne said. “It’s that kind of stuff that makes it real special.”

[block] However, if you ask Valesente about it, the accolades mean nothing. What matters to him are the connections. Connections such as Nicolo, connections such as Barer, that allow him to help his players, both current and past, on a deeper level than just their pitching mechanics or batting stance. [/block]

In a way, Dianne has found her own ways to take part in her husband’s career. In addition to raising their two children, Dianne has essentially adopted Valesente’s program.

“I’m kind of a mom to them,” she said. “That’s the connection that I have through George. I’ve been with him in this ordeal for a long time.”

Valesente’s connection with his children and wife is also one of the biggest and most important reasons that Valesente has remained at the college for all these years. After graduating in 1962, Bob became a Division I football coach, also assisting with NFL teams for several years. Valesente took notes from watching his older brother, never even considering offers from any other schools because he appreciated all that Ithaca College offered him.

“One of [Bob’s] major regrets was he didn’t get to see his family grow,” Valesente said. “Well, my job here allows me to do that. This was enough for me. As I look back on it, I’m very happy that … I never got a Division I job, and I’m very happy that I’ve gotten my years here.”

The loyalty to the program and to Valesente also runs deep with his players, both current and past, who understand just how much their coach cares about them.

“He shows up with the same passion and work ethic every day, and he expects the same out of his players,” senior captain Matt Connolly said. Valesente recently helped him get his current job at Bang’s Ambulance. “He’ll never hesitate to go out of his way for you and make something happen.”

For Valesente, it’s these relationships that make it all worth it. But there’s another main component, an obvious component. Forty-three years, season after season, being around the game has never gotten old, never become monotonous. It has never become a job.

He approaches each practice with the same pure enthusiasm as he did when he was an athlete. You can tell from his eyes. As practice winds down for the day, and he makes his way toward the white chairs at the far end of the arena, his eyes will occasionally light up from behind his glasses when he sees an athlete make an exceptional play.

This excitement, this pure, child-like joy for baseball that Valesente retains, is the reason he’s never considered retirement. He laughs when he’s asked about retirement. He says when he sees himself holding the program back, he will step down. But he’s the winningest active coach in Division III, and his teams’ records haven’t even come close to dipping below .500 in years. For him, retirement is but a speck on the horizon.

He knows it will come eventually though.

“I take it a year at a time,” Valesente said. “If I feel like … I’m too old and the program is going to suffer, I will leave then.”

Perhaps it is for this reason that Valesente’s countenance drops just a little — it’s almost unnoticeable — when he thinks about leaving the program that he has built. He sits back for a moment, eyes clouded with emotion, remembering, as the snow continues to fall outside.

“I’ll be honest with you, it’s gone by in the blink of an eye,” he says. “It’s hard to believe that it’s been that long, and it’s hard to believe that I’m still here to do it.”

March 14, 2015:

The white blur that is Sanders’ pitch seems to move in slow motion toward the Spalding University batter, who swings and grounds the pitch to second baseman Josh Savacool. It’s an easy play for the sophomore, who scoops it up and throws it lightly to Connolly at first base, effectively ending the game and simultaneously cementing Valesente’s legacy.

One thousand wins, all in the same place. It seems almost ironic that it is here in California, under the baking southern sun, so far from the place he has built his career and raised his family, so far from the familiar field that is part of a familiar campus, so far from home, that Valesente has set the capstone of his 37-year career.

At this moment, emails are flooding Valesente’s inbox and his cellphone is lighting up with dozens of messages from former players and colleagues. All want a chance to congratulate the man that has given them so much, given the program so much.

Always humble, Valesente remains calm as his players celebrate around him, gracefully avoiding the cooler of water that they attempt to pour over him.

“I guess it indicates longevity,” Valesente said. “I never imagined that it would happen. I had no goal or no plan for this to happen.”

But it did. When Valesente returned to his alma mater, he was a newcomer, a young coach with big dreams. Thirty-seven years later, he remembers driving up to South Hill on that first day of work as if it were yesterday, overwhelmed at the idea of taking over the program after a history of legendary coaches. He couldn’t have possibly predicted — no one could have possibly predicted — what it all would turn into. Over the years, his dreams have become reality. Now he is a living legend. But he would never admit it.

“I’ve never evaluated how good I was as a player or a coach,” he said. “I just play and I just coach and go home. But it has been a true honor to have been coaching here for this long.”