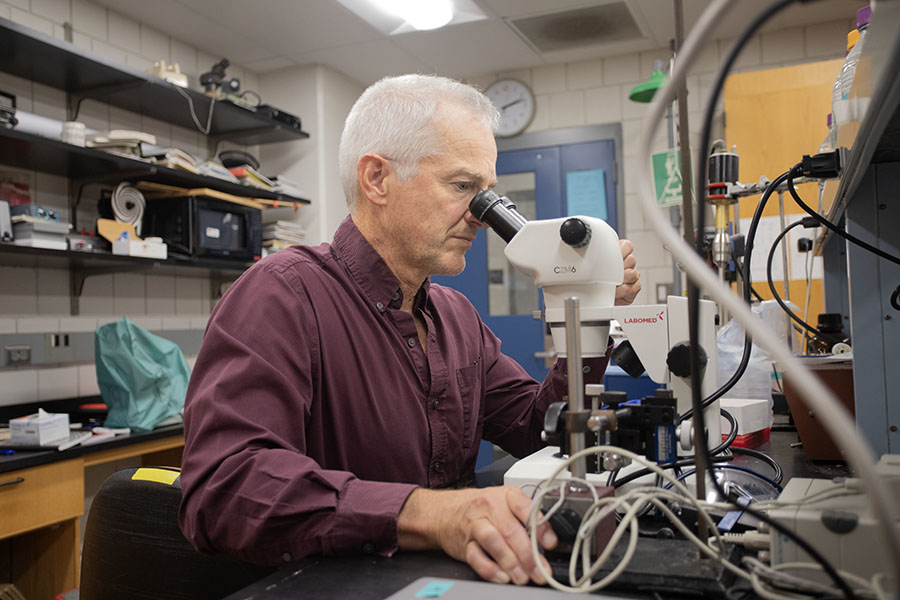

For over 20 years, Andrew Smith, Dana professor in the Department of Biology at Ithaca College, has been researching the Arion subfuscus , an invasive species of slug originally from Northwest Europe that is now commonly found in Ithaca and across most of Eastern North America. His research has been featured as the cover article of issue 24 of the scientific journal Soft Matter.

The slug has a defense mechanism and produces a unique glue-like secretion when under threat. Smith said he discovered this quality within his first couple weeks of moving to Ithaca in 2000.

“There was definitely an ‘a-ha’ moment because it was when we first got here, probably within the first couple weeks,” Smith said. “I picked up [the slug] and it just started oozing on me. It got on my finger and I rubbed my fingers together and couldn’t get it off. I was like, ‘This is incredible. This is amazing.’”

Smith’s curiosity gave him the inspiration to create a product artificially in the lab based on the chemistry of the slug’s natural properties — a medical adhesive that could replace the need for stitches or staples. The idea would not have come to him unless he picked up a slug in his backyard.

“I think most people would say it’s disgusting, it’s an orange slime all over your hand and you can’t get it off,” Smith said. “But I was a material scientist, and I knew that something that stuck like that and wouldn’t come off and that set so quickly was really special.”

The research has evolved drastically in the past 20 years. Smith started his research by studying the slug’s mechanism to produce its secretion, which was done by taking micron-thin slices of the slugs.

Since then, Smith has been working with students in his lab to attempt to synthesize a glue based on the slug secretion. The glue could, in theory, be used in medical settings and would be much more compatible with the human body than the available medical adhesives.

“The reason I’m excited about this is because gels, from a medical point of view, are really, really useful,” Smith said “We say our body is 70% water, but it’s not water that’s flowing around, it’s water that’s trapped in a gel … A lot of our structures are gels, so it’s very compatible.”

Medical adhesives are becoming more common, with Dermabond being among the most popular according to the National Institute of Health. It is incredibly sticky and durable and sets quickly, but its main drawbacks are that it is inflexible and expensive.

One of Smith’s students, junior biochem major Caitlyn O’Dell, has been working in Smith’s lab since Spring 2023.

“At first, we were making these blocks of gel and running them through cheesecloth to try and make small gels that could later be put together,” O’Dell said. “But we were finding that we needed more surface area and the way you do that is you make the gel smaller.”

O’Dell approached this challenge with the idea of using an emulsion: a mix of oil and water. She and the other lab students conducted many trials, changing variables and recording differences in their findings.

Sophomore biology major Artan Isom began working on the slug adhesive in Smith’s lab in Spring 2024. Isom intends to pursue a medical degree, and has already seen how a biomedical product like this could be useful through his experience in Fall 2022 working as an EMT. There are similar products already on the market, like Traumagel and Dermabond, but these products have their own shortcomings.

“In a lot of surgeries they use super glue or some sort of plastic, but it’s generally not the best solution,” Isom said. “[Medical superglue is] toxic. It’ll stay in your body and can cause inflammation, but your tissue can grow through [a gel] and use it like a vessel.”

Sophomore biochem major Alys Pop has also been working in Smith’s lab since Spring 2024 and the research has altered her postgraduate goals.

“I was initially in between going the medical route and going the lab route,” Pop said. “With this experience I learned that I want to work more in a lab setting or go into biomedical engineering. I’d love to be able to work in a lab and be able to synthesize materials and work alongside medical professionals.”

The pace of research in Smith’s lab has become more rapid recently, but because of the nature of the work, it is unclear when the adhesive will be commercially available. Once the medical adhesive is made, it still has to undergo human trials and get approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

“It was probably a year and a half ago that I really started aggressively trying to make a glue,” Smith said. “It could happen in two months, or it could happen in five years. I feel like if I don’t have it in five years, somebody else will.”

According to Smith, the research is very novel, but there are several scientific communities working on creating a gel product like this, including a lab at MIT.

“We published this paper that did give a fair amount of information to other people who are trying to make glues, so that’s going to accelerate the pace,” Smith said. “Maybe somebody else will get it, but there’s a bit of a moral obligation there. If we can get a glue out into the world three years sooner, even if it’s not me that does it, it’s three years sooner that a very useful material exists.”

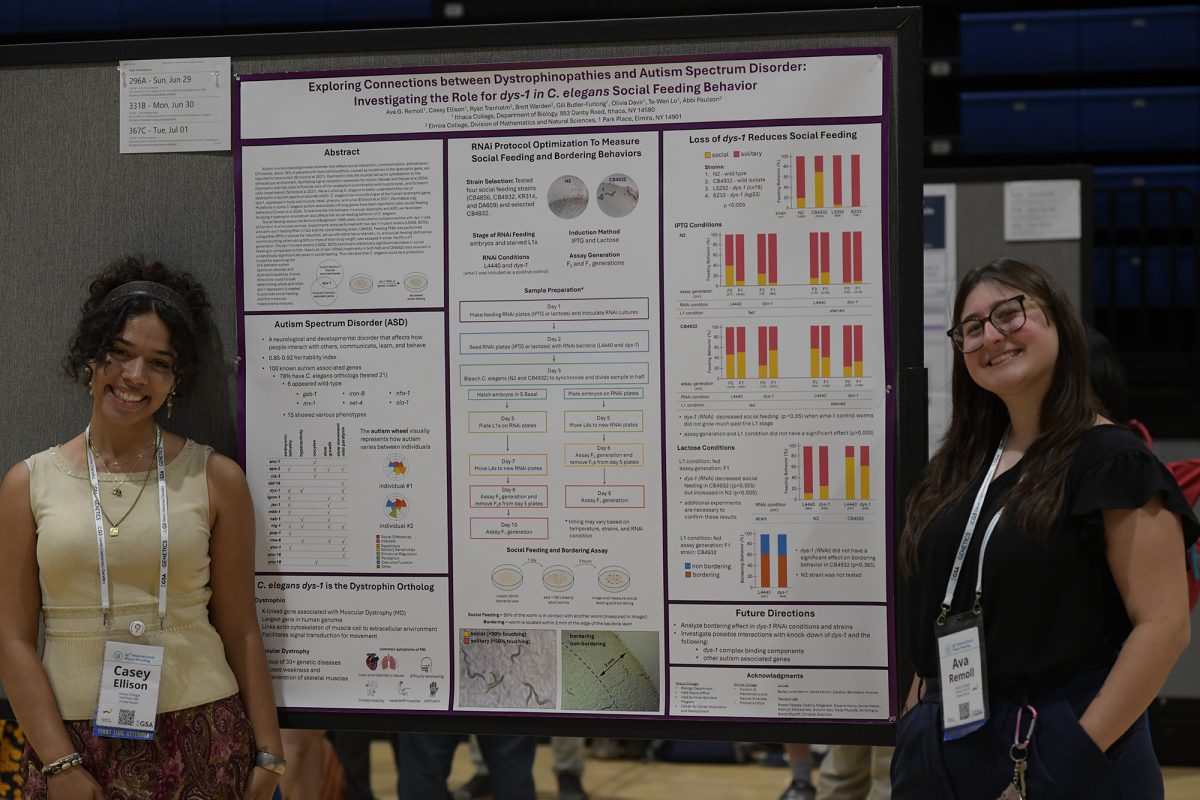

Last year, O’Dell presented her part of the research at the American Chemical Society in New Orleans in March 2023, soliciting opinions from people in the scientific community to build future research off of.

“I spent the whole conference with a notebook,” O’Dell said. “I got a lot of suggestions from that conference. It’s amazing how people work together like that, and it’s nice getting together with a large group of people who may not know exactly what you’re talking about because your research is specific to you, but because they have a better idea of science at large, they have ideas.”

O’Dell said that lab research can be repetitive and lonely at times, but that Smith’s passion is contagious and inspires his students to persevere.

“When I met Andy [Smith] for the first time and spoke with him, I remember him being very enthusiastic, and that has not changed,” O’Dell said. “He’s extremely excited about his research, and he’s very excited to tell other people about it, and that makes a huge difference.”

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly claimed Dermabond is toxic; it is not, but other commonly used medical adhesives are.

Lynda • Sep 16, 2024 at 7:06 am

Great to see an update on Dr. Smiths research! I worked as a student tech in his lab 20+ years ago. His enthusiasm also was apparent in the classes he taught. I still have vivid memories of him rolling around the walls of the classroom and, another time, giving us all tennis balls and told us to throw them at him. Such unique research and teaching style!