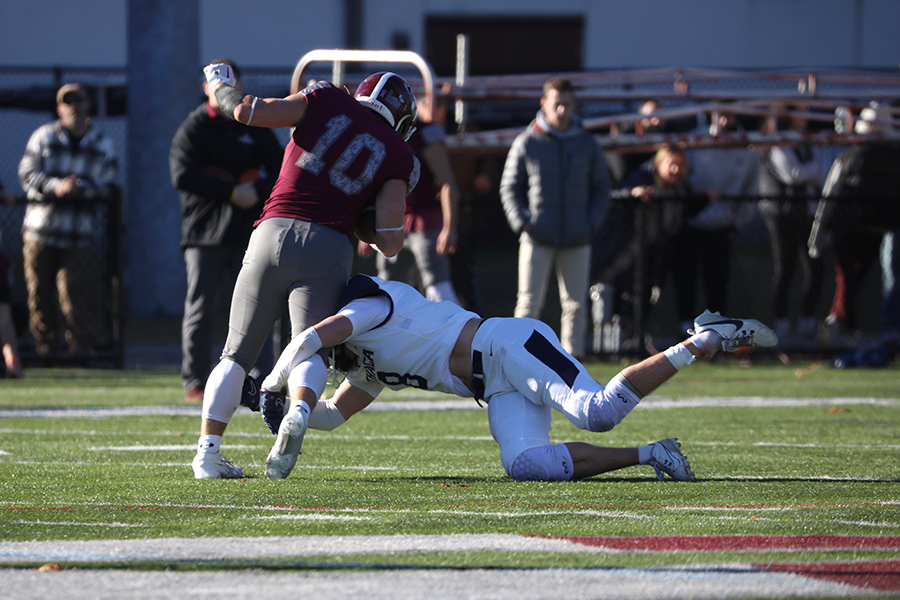

During his time at Ithaca College, Joe Fitzgerald ’93 led his football team to its third and most recent national title in 1991 as quarterback. Since then, he was a member of the 1996 United States Olympic handball team and was inducted to the college’s Hall of Fame in 2017, all while serving the Catholic seminary since 2001.

This past summer, Fitzgerald was one of 120 religious chaplains invited to the 2024 Summer Olympic Games in Paris. For the first time ever, the world’s largest athletic stage hosted this multifaith cohort to provide spiritual support for the athletes.

Senior writer Tess Ferguson spoke with Fitzgerald about his own experience as an athlete, his role at the Olympics and the intersections between his faith and athletics.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tess Ferguson: What drew you to priesthood? Is that something that Ithaca College prepared you for?

Joe Fitzgerald: It certainly helped. I grew up what they call “cradle Catholic,” so my parents were very faithful. My dad was an athlete, so that was a big part of my life, and I got to watch him participate in church even as an adult, which was super important to me. When I first got to IC, the first thing that [the football team] did was run testing. When I finished, I poked my head into the chapel thinking, “We made it, thank God that’s over.” I was surrounded with people who had a sense of faith and the beauty of IC is there were Catholics, there were Jewish people, there were non-denominationalists, there were atheists. There was always great conversation; I could always be who I was.

TF: How did you end up transitioning from collegiate football into handball?

JF: My high school principal was a chairman for soccer, and he was at an event up at Nottingham High School. When he opened up the gym door, they were playing handball and he loved it. He brought it back in the mid ’70s and put it into the curriculum of our high school — they actually still play back at North Babylon High School, where I grew up. Seven guys from Babylon went to the U.S. national team for handball, and two of us went to the Olympics, so it was a great investment. Even when I was at Ithaca, I was playing in the summers.

TF: Speaking of playing at that elite level in the Olympics, I’m sure those pressures are super high. In your experience, is religion something that you used to deal with that?

JF: I remember there was one point when I was in the Olympic Village where I needed to find some space. They had a health center with a room that was almost what a chapel would be nowadays. I went there and I found some quiet. It wasn’t easy to get to a church in Atlanta, but I do remember praying. My faith was important. Even when we were training — whether we were back here in the states or overseas — I would find myself looking for a church. It was a part of my core.

TF: How did you use that experience to help guide the athletes you worked with this summer?

JF: I certainly did interact with some of them. I prayed with them, I celebrated mass when they came, but the great conversations came with, believe it or not, past Olympians. Seeing a priest opened up a lot of questions, and I was able to explain to people that I’m here to support the athletes through the good, the bad and the ugly. They would tell me they had a nervous breakdown, they went through a divorce, they went to all these kinds of things and many of them had some kind of a connection with God. It’s such a good thing for the athletes to have some place to go. Some say, “You’re an Olympian, you’re supposed to have it all together. You’re made of steel.” We’re not, you know? We’re made of flesh and bone, and sometimes we hurt and we struggle.

TF: How did this role come about for you?

JF: The Bishop at the Diocese of Rockville Center is the representative of the United States Bishops when it comes to sports. Things like the World Cup, the Super Bowl and the Olympics, we’re trying to have more of a spiritual presence there. He brought up to me that this is the first year they’re hosting chaplains at the Olympics and that he wanted me to be one of them. Mental health has a bigger presence than ever in sports, so this kind of coincided with that, and it wasn’t just Catholics. It was Hindu, it was Muslim, it was Jewish, it was non-denominational Christians. It was great. There were 120 chaplains total and 40 Catholics, so it was a pretty cool experience.

TF: What advice would you offer to IC student-athletes who use their faith to cope with the pressure of their sport?

JF: I would say to find your identity. I know that can be taken a lot of different ways. My identity is that I’m a believer; that’s where my worth and identity is based. So if you score nine goals in the national championship game, you’re an amazing and beloved child of God. If you sit on the bench, you’re an amazing and beloved child of God. To stay in that place doesn’t take away from the hard work and the striving and the competitive edge, but what I’ve seen is when people have set their identity in their competition and then — I pray it never happens to any of our IC athletes — you blow your knee out, or something happens in your family or in school and it affects your whole season, or the week, or your career. If you’re set in that identity and worth of just the sport, you’ll always be disappointed. Your sport can be part of your identity, but it’s just a snapshot of your life. My advice is to strike that balance and find your identity on a bigger scale.