The darkness began to settle in, seeping into the left periphery of his vision like a rolling fog, resembling a crescent slowly travelling across his view.

He grasped his mother’s face, clinging onto the last straws of cloudy vision.

“If I lose my vision completely, I want your face to be the last beautiful thing I may ever see.”

Then, he was wheeled away into eye surgery on July 15, 2010, and when he woke up, the crescent had become a full moon.

—

“Your son has leukemia,” Dr. Irene Cherrick said. “He has a mass the size of a football in his chest. I don’t have time to talk to you anymore — I have to go save your child, and Dr. Trust is going to explain everything to you.”

At 2 p.m. April 3, 2010, the parents of then-14-year-old Tim Conners had just had the air punched out of them. A sudden announcement like that, after being kept in the dark amid a scurry of activity the entire morning, had them sitting in the room on the 12th floor of Golisano Children’s Hospital in Syracuse, New York, with more questions than answers as Dr. Stewart Trust calmly explained to them the ramifications of Tim’s T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

ALL — a quickly developing type of blood cancer, hence termed “acute” — grows in the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, which are found in the soft part of the inner bone. The cancer attacks by invading the blood and spreading to the body’s vital organs such as the liver and spleen, having a fatal effect within a few short months if left untreated. When caught early, survival rates for adolescents with ALL typically stand around 72 percent. Tim’s variation, T-cell ALL, accounts for 15–25 percent of all cases of ALL in children and adults.

[block] ALL — a quickly developing type of blood cancer, hence termed “acute” — grows in the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, which are found in the soft part of the inner bone. The cancer attacks by invading the blood and spreading to the body’s vital organs such as the liver and spleen, having a fatal effect within a few short months if left untreated. [/block]

As the cancerous lymphocytes were traveling along his bloodstream the evening of April 2, 2010, Tim was having difficulty breathing while his mother, Betsy Conners, stayed up with him until he tried, and mostly failed, to fall asleep.

“I’m struggling to breathe, I’m terrified to go to sleep,” Tim was saying.

Despite assuring herself that the doctors from the previous week’s visits could not have missed something, she took him to the doctor in the morning anyway.

When Tim’s normal pediatrician was not in the next morning, Dr. Trust took his appointment and knew immediately from looking at him what was wrong. Without an explanation, he immediately urged them to go to the hospital, where Tim and his family would bypass the emergency room and go straight to the 12th floor.

“Time is not on our side,” Dr. Trust had said.

Many possibilities were floating around his mother’s mind — meningitis, some other virus — as she drove home to pick up her husband and told him to hurry to the hospital.

Tim remembers the big fish tank in the hospital, the Cold Stone Creamery and the room full of XBox 360s and PlayStation 3s. He also remembers drinking one glass of water and throwing it right back up.

The hospital was buzzing with people running around, but Tim’s parents didn’t know what was going on as they tried to keep Tim’s spirits up. Dr. Cherrick finally came in, and with a sense of urgency, took Tim’s parents to a room to speak to them. In the room was the pediatrician from earlier that morning.

After Dr. Trust explained the next few steps — a spinal tap, bone-marrow transplant, chemotherapy — Tim’s father, Michael Conners, went to Tim’s room, where he was being prepared for treatment, to deliver a message.

“You have an 80 percent chance of beating this, Tim.”

“You have an 80 percent chance of beating this, Tim.” [citation] Michael N. Conners [/citation]

—

During his freshman year of high school, Tim was most excited for the track and field season. He threw discus and shotput, but he soon struggled with symptoms of sinus infections and allergies. He was getting sicker, receiving steroids to treat the sinus infections, taking trips to Urgent Care. After having surgery to remove his wisdom teeth, he had symptoms resembling Bell’s Palsy, where half his face drooped as if he had had a stroke.

“I was very self-conscious,” he said. “It was weird, because I don’t think a lot of people knew how to act with me.”

But the treatment he received made things worse. The steroids he was receiving to treat the infections were also having a nearly negligible effect on the leukemia, treating it slightly, but mostly just masking it. Leukemia can also reveal itself through swollen and bleeding gums, but these, too, were thought of as mere symptoms of the wisdom teeth surgery. The cancer was infiltrating his central nervous system, and it began to manifest itself on a psychological level.

During his older brother’s “senior night” wrestling game at the end of February, Tim would not come out of the locker room. He had been overcome by a panic attack.

“I can’t do this, I can’t do this,” Tim kept repeating as his mother, the athletic trainer and finally his pediatrician were able to coax him out. It was Tim’s time to wrestle, under the eye of his father, the varsity coach.

Betsy emerged from the locker room minutes later, confused and lost as to the whereabouts of the Tim she knew, and walked over to her husband.

“He’s not coming.”

—

In July 2010, just three months after the ALL diagnosis, the cancer came back in Tim’s optic nerves, resulting in a level of pressure too high for his eyes.

“Relapse is rare, but relapse into the optic nerves is rarer,” Tim said.

Tim had gone into remission within the first month of his diagnosis, after receiving a triple dose of chemotherapy through the spine on April 3. Having caught the cancer at its already advanced stage, the doctors felt the intensity of treatment necessary to immediately save his life on that day. But as any cancer survivor knows too well, remission is only a temporary and uncertain state of relief.

The morning of July 15, Tim noticed the crescent forming in his left eye, thinking it was from watching too much television.

He didn’t fully realize it would be the last television he would watch.

Betsy took Tim to the emergency room that morning to find a series of dead ends and question marks. The blood tests returned normal, but the CT scan revealed bleeding behind his eyes, in his optic nerves, though the reason for the bleeding was unknown. Nor did the young doctors, fresh out of medical school, know if they could stop it.

“This young doctor comes up, and I guess he never had to deliver bad news before, and he said the cancer had come back in my eyes,” Tim said. “I just remember so much happening, but I know the pressure in my eyes was so high.”

No one knew what to do. Tim underwent radiation treatment to no avail, then prepared himself for a spinal tap without an anesthesiologist on call. His father went in to hold him down, as his mother waited outside, listening to his screams. In a panic, she called Dr. Cherrick, who ordered those on staff to halt everything until she arrived in the hospital the next morning.

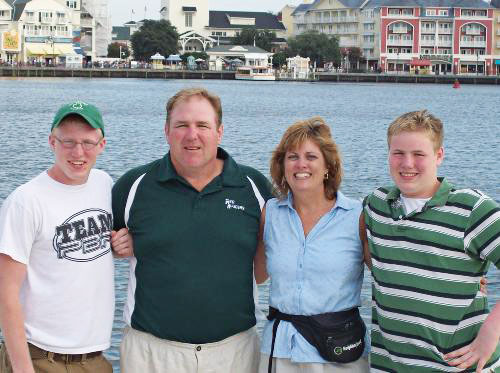

From left, Tim’s brother, Michael P. Conners; his father, Michael N. Conners; his mother, Betsy Conners; and Tim vacationed in Disney World in July 2008, before the diagnosis.

The goal of the surgery that morning was to relieve the pressure in Tim’s eyes and save the optic nerves so that, even though Tim was already going blind, they might have a chance for a transplant. The operation failed.

“For me, that was more devastating, even than the cancer, was when Tim went blind,” Betsy said.

As a result of cases like Tim, which are extremely rare, studies now suggest doctors perform routine ophthalmic examinations along with the patient’s evaluation upon being diagnosed.

The day Tim went blind, Betsy received a call from Tim’s older brother, Michael, who, out of anger, had punched a hole in a door at home.

“What’s the matter with you?” she said to him. “Go up and punch one for me!”

That door, now with two holes, will never be replaced as long as Betsy lives in that house, she says. Betsy looks at the door and thinks, ‘That’s the day Tim went blind.’

—

Radiation and chemotherapy treatment are enough to alter one’s life in dramatic ways. Often patients will gain weight that is difficult to shed as the therapy renders the body cripplingly weak, among other visible side effects like hair loss and general fatigue. Tim’s tall figure carries some of these effects — his hair is thin and balding, his stomach is rounder than it was during his football days. But blindness, a new onset for Tim, who had normal sight for the entirety of his childhood, was even more difficult to cope with.

“Even when he first went blind, he refused to learn braille, because that meant he had to accept being blind,” Betsy said. “His grandmother would say, ‘Oh I am praying, Tim’s going to get his eyesight back,’ and I finally had to look at her and say, ‘He is never getting his eyesight back.’”

Tim refers to his blindness as “the vision I have today,” and his blind life as “the new normal.” The vision is not something he has lost, but something that has changed, albeit dramatically. Tim will wear sunglasses when travelling from class to class, but during class, with his friends, during a one-on-one conversation, his eyes are exposed. At times, he appears to be scanning the room as though he can see it.

“It’s not like if you pictured a dark piece of black paper, it doesn’t look like that. When you close your eyes, don’t you feel like it’s not pitch black? That’s what it’s like for me. If you close your eyes, but you still kind of feel like … I can picture you. I can’t actually see you.”

The object of his conversation becomes a vision in his mind, and he attempts to look right at it, flickering into the eyes of the other person. It’s easy to forget that they are unseeing.

“The only thing I can sense is some light perception in the corner of my right eye,” he said, looking toward that corner and holding his gaze there for a few moments. “I think some people would imagine this black. I don’t see this black, it’s not like I look forward and there’s this blackness, and I don’t know if that’s from my past memory, being able to visualize things … it’s just kind of a fuzzy black, with what I envision things look like.”

Mobility was Tim’s first priority after returning from the hospital newly blind. His house, in which he grew up his entire life, became an unfamiliar obstacle course, but he wouldn’t have much time to settle. This was a time when his life was on the line, when his family made the decision to turn to a bone-marrow transplant to save his life, barely.

“I never felt like I was ever going to die when I was sick,” Tim said. “I just have such a strong support network, and it’s not that I don’t get depressed, or that life isn’t hard, or that it’s not tough being muscularly the way I am … I just stay positive, and I think God kept me in this world for a reason. I see it as, all of those other people that didn’t survive what I went through, me kind of being the voice for those who don’t have theirs anymore. … There is a future beyond everything that’s happened to me.”

—

Today, Tim’s blindness does not impede his involvement with Ithaca College.

Though he is a sophomore, Tim is a third-semester student, having spent 16 weeks — the equivalent of his first semester as a college freshman — at the Carroll Center for the Blind in Newton, Massachusetts, where he learned the skills he needed to be independent at college.

“I’m glad that I did it. I think that I’m a lot more independent,” he said. “There are definitely areas I can see that I need to grow in, and I’ll probably take advantage of something else maybe later in life, but right now for what I’m doing and where I’m at, I seem to be managing fine.”

Tim had applied to 12 schools, but when visiting Ithaca College, he found students to be friendly and interactive. Betsy said one girl even offered to walk them to the Student Accessibility Services office.

“It truly has been the place for him,” she said. “I am so glad he chose it, and I am so impressed with how the students are so receptive to him and open to him and don’t judge him. We always said, ‘Don’t let cancer and blindness define you.’”

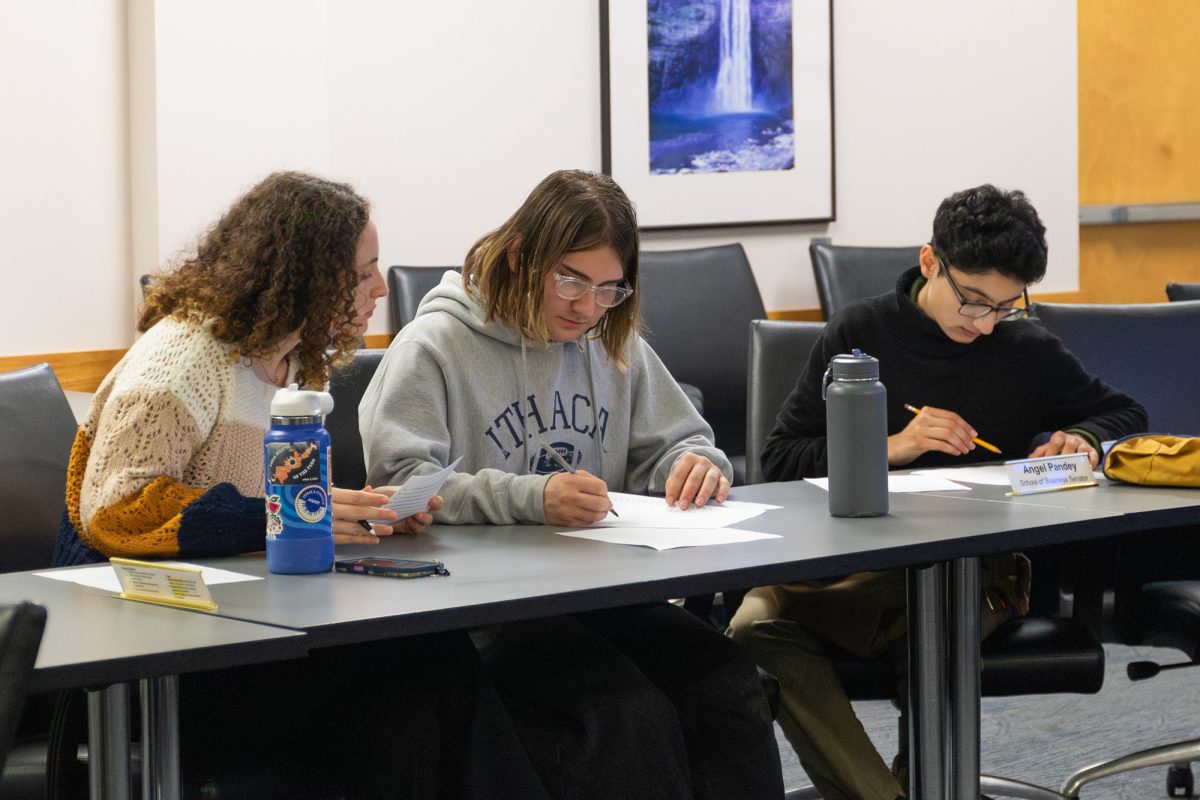

Tim sits in the Feb. 16 meeting of the Student Government Association, for which he was sworn in as senator-at-large Feb. 9. Tim said he plans to continue his involvement with the SGA.

Tim has instead chosen to invest himself in several outlets on campus, which keep him going from one club meeting to the next, and at each place, everyone knows who he is. From the Ithaca College Debate Team, to IC Colleges Against Cancer, to IC Organic Growers, Tim’s presence is noted by others, even when he’s not there.

On Feb. 9, 2015, despite not being at the meeting due to a prior commitment, Tim was sworn in by Ithaca College’s Student Government Association as senator-at-large — the first blind student to hold the position. He plans to continue his involvement with the SGA.

“You may not recognize me by name, but if I said I was a blind student who’s always walking around campus with my cane, I might ring a bell,” he wrote in a statement, which Kyle James, vice president of communications for the SGA, read at the meeting.

His mother laughs when she hears that statement.

“That’s Tim. Before and after cancer, that’s Tim,” she said.

—

Since the normal chemotherapy treatments were not working in his central nervous system, Tim entered the Boston Children’s Hospital on Sept. 3, 2010, for seven days of more chemotherapy before the bone-marrow transplant that would save his life, but not without first placing him in the intensive care unit during what was supposed to be his recovery.

Bone-marrow transplants replace the patients’ bone-forming stem cells with those of a donor, or of the patient’s own blood or marrow. The procedure must be accompanied with high doses of chemotherapy beforehand, often resulting in nausea, vomiting and hair loss. Tim’s donor was his brother — a perfect match.

Following the transplant, around 2 a.m. on Sept. 21, Tim’s blood potassium levels were reaching alarming levels. His kidneys were failing. But as the levels began coming back down two hours later, only slightly, the doctors were waiting to see if the trend would continue downward.

Betsy was not willing to wait. After calling her brother, a doctor on Cape Cod, and detailing Tim’s potassium levels, her brother urged her to invoke her parental rights and place Tim into the ICU to begin dialysis for his kidneys.

Two to three days later, Tim was not improving. Dr. Stephen Margossian was losing faith, feeling discouraged, not sleeping. He then turned to his wife, who is a renowned cardiologist.

[block] Two to three days later, Tim was not improving. Dr. Stephen Margossian was losing faith, feeling discouraged, not sleeping. He then turned to his wife, who is a renowned cardiologist. [/block]

“I’m going to lose this kid,” he said.

His wife looked at Tim’s records, and she saw.

“You’re losing him because nobody’s addressing his heart,” she said.

It was a realization that saved Tim’s life. Immediately, Tim started on heart medication, then began to turn the corner.

One night in the ICU, hearing music with a harp playing, Tim asked his mother at his bedside if he was in heaven.

“Nope, still purgatory.”

—

Though the cancer was gone after the transplant, Tim would spend the next 100 days in the hospital, hardly eating, under the influence of morphine and medical marijuana, weak and on bagged food. Only remembering his dreams from that time period. Setting goals little by little, beginning with sitting in a chair, as Betsy stayed with him for all but one night.

“That’s how weak I was at that point, that sitting in a chair for a half an hour was going to be a big difference,” he said.

He had been receiving occupational and physical therapy in the hospital, working on walking with a walker and somebody holding him up by his gait belt, a belt with handle loops. Slowly increasing distance and pace, day by day. Going home, the largest obstacle was ascending the three steps that led into the house. To say it was tough — especially for someone whose very bones had been tapped into, for someone who had immense difficulty getting out of the hospital bed and onto the commode to relieve himself — would be an understatement. Tim still has difficulty with his tibialis anterior, the muscle in the front of the legs that acts to lift the toes, preventing the feet from dropping while walking.

Pushing him out of his comfort zone was an area where Betsy took initiative. The push to go to college, the push to go to Salamanca, New York, for a service trip through IC Habitat for Humanity over spring break, the push to talk to other people in whom he could confide about social relationships.

“Life’s never easy, and if you allow this to define you, then you will not be the person I know you’re capable of being,” she said, recalling the advice she would give Tim.

—

With his sight, Tim had had a passion for cooking.

“Most people in fourth grade — what do you want for Christmas? I wanted a KitchenAid mixer,” he said. “The varsity wrestlers, they called me Timmy Crocker. Then they’d all want to eat the stuff I made. I always loved sharing food, sharing things, buying things, giving things away. That was my way of connecting. I always see myself as a poor philanthropist. … Now it’s something that would be very hard. I hope some day to get back into it.”

In other things, Tim was a very visual learner. He was the kid who could sit down to memorize a world map simply by looking at it. Those days left with his eyesight.

“I haven’t really found those new passions in life, where it’s like I wanna go and do this every day and be great at it, because I love it,” he said. “I think in some ways that contributes to a loss of identity.”

His blindness has made it necessary to pick up new methods of learning and communicating effectively, which he now seeks to do in his recently declared dual major in communication studies and environmental studies. When applying for scholarships, Tim will write down environmental law as his career interest — it’s something employers and providers of scholarships would like to see. But in actuality, he has no idea what he wants to do with his life.

“I’m concerned with being at college right now and taking advantage of everything, and I feel like things are going to fall into place,” he said. “When I know what I want to do, I’m going to do it. There’s nothing that’s going to stop me from doing it.”

“When I know what I want to do, I’m going to do it. There’s nothing that’s going to stop me from doing it.”

—

The week before Christmas in 2010, Tim arrived home after the bone-marrow transplant, too weak to move anywhere but the downstairs couch, where he stayed, only awake a couple hours at a time, being fed on bagged food and IV nutrients. What was supposed to be his sophomore year of high school was his isolation period as a result of the bone-marrow transplant.

Each morning, the hospital sent a vial of nutrients based on the content and needs of his blood. Tim’s mother would then extract vitamins from the vial and hook up his IV for 12 hours, and this was Tim’s food.

“I learned to be a nurse, things I never imagined possible,” she said.

The food bags were expensive — about $1,000 each — as were the powerful air purifiers, one placed in the living room where Tim spent his days, and one in the family room where he slept at night. These were to protect Tim’s immune system, which had reverted back to an infantile state. Tim had to get all of his shots again, nurses and outsiders were required to wear masks in the house and leave their shoes outside, and Tim was mostly couch-ridden.

His only contact with the outside world at that time was the ability, every once in a rare while, to sit out on the front porch and wave to those members of his tight-knit community who seemed to come out of the woodwork to support him.

“When I got sick, there were kids that I didn’t even think knew I existed … people that I generally didn’t know cared about me that much, were there for me, and it’s an amazing feeling to know you have that many people behind you.”

Nevertheless, there were things he missed as a sophomore living at home. He missed the parties. He didn’t have a significant other. But as a person who didn’t advocate drinking or partying, he has chosen not to think of these as missed opportunities. For his mother, it’s more the concept of him being home for one of the most important social years of his life.

“That year when you turn 16 is a big developmental year, and he missed that,” Betsy said. “His friends who went on to do typical high school things and college things, he missed all that. And I think that was probably harder for me as a mother to watch.”

The way Tim sees it now, the blindness and the cancer have been the reason he has gone on adventures and met significant people, experiences he may not have otherwise had.

—

As a cancer patient who was still a minor, Tim was eligible for a wish from the Make-a-Wish Foundation. Among his ideas were to have a big party, meet a celebrity or to cook for the President — but these all changed when the cancer affected his eyes.

After becoming blind, Tim decided he wanted to meet Erik Weihenmayer, the first and only blind man to climb Mount Everest.

From left, Erik Weihenmayer, the first and only blind man to climb Mount Everest; Tim; and Michael Conners climb a steep hill at Weihenmayer’s campground in Golden, Colorado.

Tim took his first flight to Golden, Colorado, where Weihenmayer currently lives, that summer. His family and the Make-a-Wish representatives were feeling anxious as they waited at a diner for Weihenmayer to show.

“I was just so excited, I felt like a little kid,” Tim said about meeting his idol for the first time.

Weihenmayer knew his way around, holding his drink in one hand and cane in the other as he navigated the restaurant like a familiar home. That day, Tim embarked on adventures bold enough for anyone with or without sight, going ziplining over the Colorado River and doing three rounds of whitewater rafting. Though he resisted the rafting on the first trip, by the third, Tim had transformed, jumping into the river water and having the time of his life.

“I wanted to be him, I wanted to do adventurous activities to show I could, but I wanted to make a friend, someone very successful that I could talk with,” Tim said. “I want to do all this stuff, but one of the big things he preaches is everyone has their own thing. I’m still trying to find that niche, you know?”

That evening, Tim went for his first hiking trip at Weihenmayer’s campground. There was a particularly steep hill, and up he labored, not stopping until he reached the top.

That was Tim’s Everest for the day.

—

Tim prepares to snap the ball during a practice his senior year of high school.

The Fulton City High School Red Raiders of Fulton, New York, where Tim grew up, were down by at least 30 points, getting sorely beat by Nottingham High School in the last football game of the season — of Tim’s senior-year season. But it would be the most memorable game of Tim’s life.

A cancer diagnosis, a failed optic nerve operation, a bone-marrow transplant, a year of infantile strength and immunity. After all of these trials, Tim returned to the field, but this time, his father was with another team, having taken a position of athletic director at another school, a rival school.

But Tim still played. He was there that season on strict conditions laid down by his doctors. He could play, but he could have no contact with other players. If he stayed down after snapping the ball, it would be illegal for the other team to hit him. He didn’t play until this final minute.

As the coach called him on to the field to snap the ball, the entire crowd — from both sides of the turf — rose to their feet with a mixture of tears and a roar, both teams chanting Tim’s name.

In the crowd were the kids of one of Tim’s nurses at Golisano, who later that night told their mother that “her Timmy” played in the game.

Three snaps to the quarterback, three separate plays during which his teammates blocked for him, and they made it 18 yards down the field, earning Tim the game ball. He also received one of the highest football honors from the New York State High School Football Coaches Association — the 12th man award, given annually to a player who, despite having a severe physical obstacle such as blindness, contributed to his team in a valuable way.

“There just was not a dry eye in the place,” Betsy said.

“There just was not a dry eye in the place.” [citation] Betsy Conners [/citation]

—

In class March 6, Tim knows what he’s reaching for. His movements are automatic as though he could see the exact location of his poptart and orientation of the bottle of hand sanitizer. The only difference is that his eyes are angled downward, except when he glances up toward the ceiling to think and answer questions.

In class, among his peers, Tim is not blind. People lock eyes with him. He looks directly at the person speaking or the person with whom he is conversing. At only one point does he indicate the nature of his vision, in an address to the instructor — “Which way am I going?”

As Ozge Heck, assistant professor of communication studies, splits the class, Interpersonal Communication, into small groups for discussion, Tim’s body language is open and curious. Legs uncrossed, feet occasionally fidgeting while he speaks to either the group or just the person next to him, whoever will listen.

“He is definitely really active in my class, and I enjoy hearing his ideas in relation to interpersonal communication and how he overcomes his visual shortcomings when he communicates with others,” Heck said.

Class is more than another destination or obstacle. Tim is interested about the people around him, asking personal questions in between academic discussions. Perhaps because that is his first impression — he cannot judge a book by its cover simply by looking at it.

—

The week leading up to the college’s annual Relay for Life was crunch time for IC CAC, an organization Tim has supported since he arrived at the college.

Catie Ihrig/ The Ithacan

From left, Tim, Betsy Conners, Michael N. Conners and family friend Sue Darling attended the college’s Relay for Life on March 21, sporting orange sweatshirts that read “Tug for Tim.”

But of course, he was not new to Relay. Fulton hosted one every year, except the year of Tim’s diagnosis, when it was moved to Oswego.

At its March 17 meeting, IC CAC was alive with chatter about last-minute fundraisers, social media and the final schedule for the relay. It was this time last year that they were discussing Tim’s involvement as the featured speaker of the 2014 Relay for Life.

“I just want to walk into public areas and shout ‘Relay for Life! 2 to 2 on Saturday!’” Tim said amid discussions of how to promote the event and garner campus buzz.

“I encourage that, Tim,” senior Chad McClelland said. “We can take a walk right now.”

The day of Relay For Life on March 21 at the college brought a consortium of student teams sporting different brightly colored T-shirts, collecting beads on strings to count the laps they completed during the 12-hour-long marathon of walking and entertainment. Tim’s table had raffles, lollipops and bracelets for sale, all the proceeds going to Relay. His parents were there in support of him, the cause, a lifetime of thanks for the cancer research dollars that saved his life: wearing orange and taking the occasional lap, a slow stroll, in no hurry to cross any sort of finish line yet — just to keep walking on.

The bracelets read, “Cancer bites and I’m biting back.”

—

With the harness in place on his hips and tight around his upper thighs, Tim braces himself, standing with feet wider than his shoulders, hands on hips, stepping side to side and lifting one knee at a time as though preparing his joints.

He’s facing a wall. A rock wall.

Tim climbs the rock wall in the Fitness Center with the help of a student staffer April 9.

The student staff member leads him slowly toward the wall with one of Tim’s arms outstretched until it makes contact with what will be his first stronghold. As his left hand searches the wall for another sense of security, his legs brace for the leap — a slight bounce in his step, and up his right leg goes onto another rock.

“Left a little bit from there … down … just missed it … yeah, that’s it.”

It’s a constant conversation between Tim and the student staffer, asking and feeling for his options with each step. A couple rocks up, and the left foot begins to waver, searching for a rock without success.

“I’m gonna come down, OK?”

Back to the beginning, but not out of breath or showing signs of nervousness, Tim keeps his head staring straight on as he begins the ascent again. This time higher than before, his body straddles across the rocks, and only now has he begun shaking. He loses his footing and is hanging on by only his hands.

“I’m gonna come down, OK?”

He stands with hands on hips again, this time pondering. Strategizing.

His hands feel from rock to rock as though he has now memorized the grid, progressing more quickly now, finally reaching a brown rock with a sizeable pocket for his big hands, regains control over his right foot that slipped momentarily. Takes a breath.

“I’m gonna come down, OK?”

That was the highest he had reached on the wall that day, yet another small Everest in that moment.

Tim still has a few odds stacked against him. He might need a kidney transplant in the next 20 years. There’s a chance he might not regain full nerve functioning in his legs. But Tim is taking measures to beat the odds. He attained official survivor status at his April 6 doctor appointment at Golisano, and he was recently approved to receive a guide dog through Guiding Eyes for the Blind. He’ll be working with kids at Fulton’s Catholic Youth Organization over the summer, and he’s applying for a $12,000 scholarship through the National Federation of the Blind. Turning can’t-dos into must-dos and deflecting negative thoughts that might hold him back.

“I face challenges now, but I feel like I’m resilient, I’m persevering,” Tim said, reflecting on the past five years. “I think that confidence has come into me, and trying not to be afraid, and trying just to be myself, and be OK and be proud of who I am and I think those were a lot of things that came about from everything I had gone through and experienced.”