The Center for Theater and Dance Productions at Ithaca College opened its proper mainstage season with “Our Town”, Thornton Wilder’s reflection on the nature of small-town American life, which ran from Oct. 14 to 19. Directed by Cynthia Henderson, professor in the Department of Theatre and Dance Performance, this production delivered an emotional and compelling message about the inevitability and uncertainty of death.

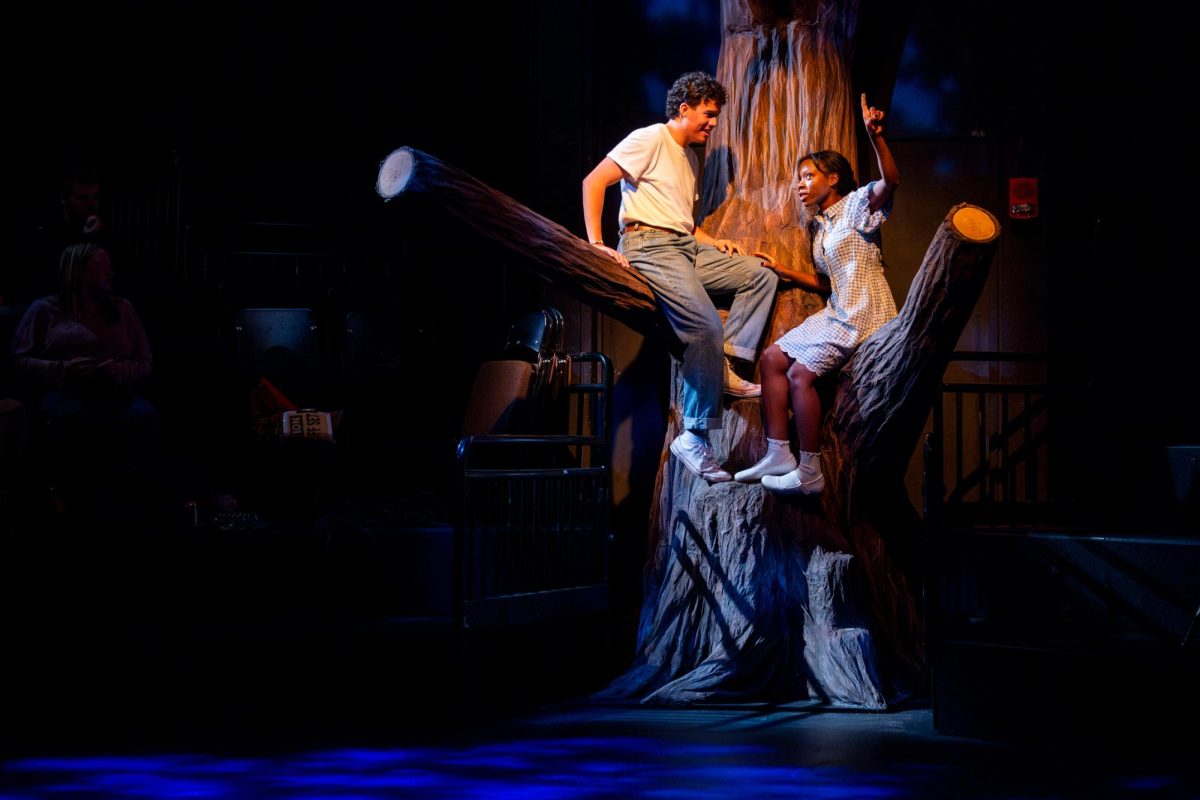

Set in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, this fictional small town mirrors the broader human experience and people much like those I grew up around. At its center lies Emily Webb, played by senior Corrinthea Washington, and her story of young life, love and the ignorance that comes with mortality.

Performed in the round, the production’s scenic design by senior Tanner Foley was strikingly bare, emphasizing the show’s minimalist traditions. Around the edges of the audience were wooden cut-outs of town landmarks that evoked a sense of centrality. The floor’s circular brick patterning and wooden inside anchored the playing space to feel like that of a town center. The simplicity succeeded in putting the story’s focus on the people of the town and their stories.

Props were used sparingly, a choice that heightened the production’s minimalism. Most actions were pantomimed, at first feeling oddly placed against the select props utilized. The props put into place were a baseball for George Gibbs (played by senior Kaden Hawkins), a handful of books for Emily, a book for Wally (played by sophomore Michael Lazovitz), two strawberry phosphates for the young lovers to share, and flowers for the graves. At first, an explanation for the selectively used props is for emotionally impactful moments revolving around love, but Wally’s book complicates that notion.

Costume design senior Madden McLeod, assisted by junior Hana Fiona, extended this simplicity to the clothing by balancing period evocation with a timeless feel. Despite the characters being generally more dressed up than down, no costume felt truly dated. The choice to retain the masculine costuming for Dr. Gibbs, played by junior Charlie Jurta, despite the gender change in casting, raised questions about the show’s intentions. While the intention toward representation was clear, the adjustment clashed with the dated text at times, notably in the fatherly lecture to her son George. Within the original, that speech carries the subtext of ‘man up,’ but when delivered by a lesbian mother, it calls for a different resonance that was not clearly delivered when paired with the costume choice. The production needed to commit to the gender change of Dr. Gibbs. The casting should have reshaped and added to the story rather than simply coexisting.

The lighting design by junior Brady Fiscus complemented the scenic choices with subtle storytelling. The lighting shifted between warmer, natural tones for daily life; harsh lighting illuminated the grounded yet charming narrator character, the Stage Manager, played by senior Alex Ross; the cold, blue tones defined the final act’s exploration of death. Fiscus’s use of lighting added to the story, easily denoting time and space without ever pulling focus from the story.

Sound design by senior Theo Roe was the cleanest and most cohesive technical element. During the Stage Manager’s introductory speech, noises of a busy town played, with a train’s whistle being particularly noticeable. The whistle was then utilized to signal a time jump to another moment of Emily’s life. This was skillfully combined with a spotlight on the clock tower cut-out with central lights spinning to denote these time jumps. A particularly striking aural moment came when the character, Simone Stimson, the choir director, conducted her singers: the sound filled only the section of the audience she faced, creating a powerful sense of localized sound.

Among the ensemble of actors, Simone, as played by senior Eislinn Gracen, emerged as the most deeply felt character of the night. Her portrayal of a tragic town drunk — one gossiped about, yet pitied — carried a compellingly haunting empathy. She became the tragic conscience of the community, prompting reflections on how we understand not only our own lives, but also asking a powerful question about how we perceive the invisible struggles of those around us.

In classic Professor Henderson style, the production began before any words were spoken, most recently seen in her 2023 production of “Newsies”, which opened with an early morning in the city. During the preshow, several actors entered quietly, sitting on the wooden crates used throughout the show. They repeated gestures in silence until the lights dimmed. Only after intermission did the meaning of this image bloom: these were the future dead members of the town, already waiting in their graves. The effect of this was subtle yet deeply chilling and poetic once the addition of Emily to the graveyard is revealed.

Despite its compact beauty, the production felt emotionally distant. I found myself watching the characters’ emotional journeys rather than experiencing them. The existential musings of the dead Simone and the ever-charming Stage Manager resonated with me deeply, clearly dissecting the bliss of ignorance. However, other audience members were brought to tears by the raw grief of Dr. Gibbs and George during Emily’s funeral. Afterward, I felt the need to ask myself: to whom was I supposed to connect?

In Emily’s return to her younger self’s birthday, the production found its quiet power. As she relived the day knowing that it would all inevitably end, her attempts to reach out to her mother captured a devastating truth: living in ignorance is “what it is to be alive.”