Ithaca College’s Student Government Association’s recently completed vote of no confidence on President Tom Rochon and the faculty vote of no confidence currently underway can be understood in the context of similar actions at colleges and universities nationwide.

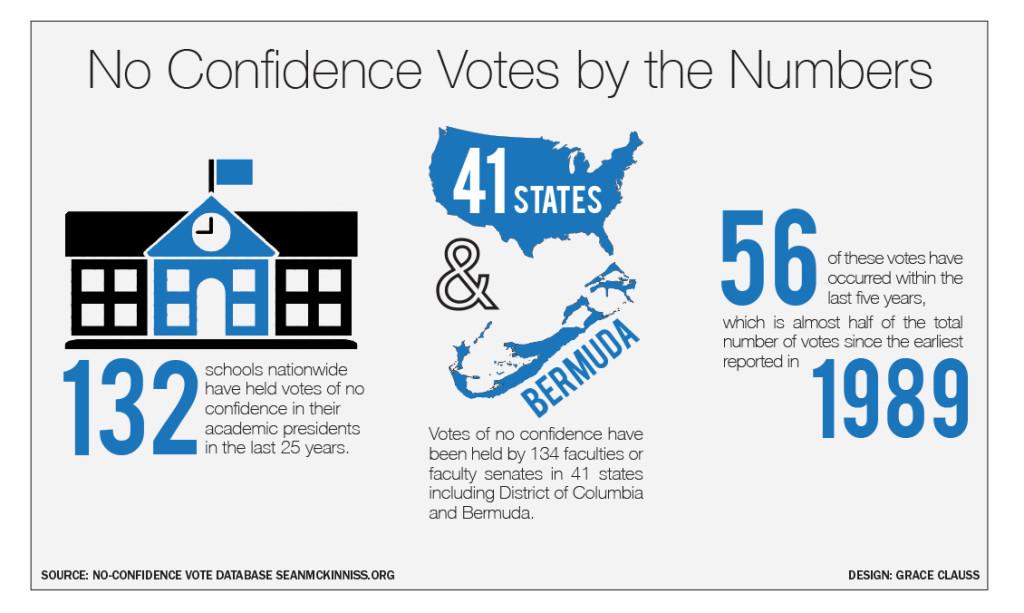

The results of the faculty vote will be reported Dec. 14. These votes have made the college one of 132 schools nationwide that have held votes of no confidence in their academic presidents in the last 25 years.

Votes ranging from small colleges to large state universities have been held by 134 groups of faculty or faculty senates in 41 states including the District of Columbia and Bermuda, according to research by Sean McKinniss, a graduate student from the Ph.D. program in Higher Education and Student Affairs at Ohio State University. Fifty-six of these votes, almost half, have occurred within the last five years, with the earliest reported in 1989.

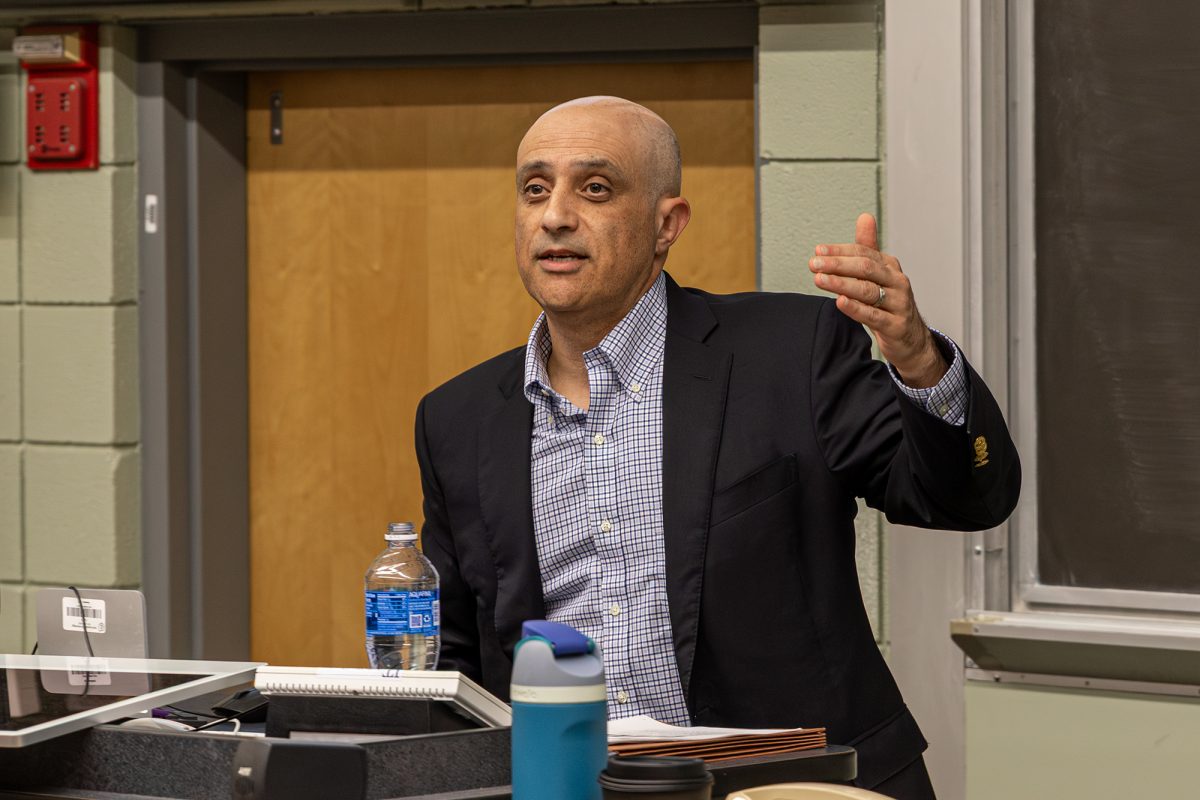

McKinniss, who is the creator of some of the most comprehensive research and a database compiled on the issue, attributes the volume of no confidence votes in recent years to the ability of faculties and students to organize and share concerns with each other and leaders via the Internet and social media. He also credits responsibilities like budget cuts, demands for accountability and cutting student debt as making presidents open to more scrutiny.

In his research, McKinniss found that student-led votes of no confidence are rarer than those of faculty. He attributes this to the involvement of students and their other commitments on campus that may prevent them from being as aware of the leadership than faculty.

“I think that they generate more publicity than a faculty vote because faculty votes happen several times a year,” McKinniss said. “When you see a student vote it really is a rare sight in higher education, and it can send a message that students are fed up with the leadership in perhaps a stronger way than even a faculty vote could … It takes something like what has happened at Ithaca to bring students out of their traditional roles and become involved.”

McKinniss said most presidents who receive no confidence votes remain in their seats immediately following the vote, but usually leave within a few years — sometimes as short as six months.

“Usually presidents leave,” McKinniss said. “After votes there is a pattern of presidents leaving, but whether or not that’s due to the no confidence vote often remains unclear.”

Outcomes of no confidence votes are difficult to interpret, McKinniss said. He said oftentimes a president’s departure or continued improvement cannot be directly correlated to the vote as evidenced by data, but can be inferred. But according to his analysis of the 132 votes of no confidence to date, he said a pattern has emerged.

McKinniss said the pattern is a “gradual process” marked by a gap of time between the vote and the president’s departure. This period he believes is to allow the president time to find new work, then they leave the institution.

Typically, he said the president and the board never explicitly say the vote of no confidence was the cause of the departure when they announce their resignation. McKinniss attributes the departures to the “irreparable damage to relationships,” that no confidence votes can cause among the campus community.

This is not the first time a vote of no confidence has been discussed by Ithaca College faculty. On Sept. 5, 1995, the Faculty Council voted down a motion to move forward with a vote of no confidence in then-president James Whalen. The vote was canceled due to Whalen’s announcement that he would be stepping down at the end of the 1996–97 school year.

According to the Sept. 7, 1995, issue of The Ithacan, initial talks of the vote were brought up in light of Whalen’s controversial downsizing at the college and scrutiny of his perceived autocratic leadership style.

The source of most no confidence votes, said McKinniss, comes down to four common causes: perceived violations of shared governance by the president, financial mismanagement on the president’s part, an unfavorable leadership style and personal misconduct on the part of the president.

“The No. 1 reason the faculty votes against presidents … are the faculty perceive violations of shared governance,” McKinniss said. “They think the president is being non-collaborative, is being dictatorial or autocratic. They think he or she is not respecting the culture or the traditions of the institution.”

Illustrating this point, colleges at New York University held multiple widely publicized votes of no confidence against their president, John Sexton, during the spring of 2013. The New York Times reported that four colleges held “overwhelming” votes against Sexton, including the College of Arts and Science, NYU’s largest school.

Ultimately, the board stood behind Sexton, releasing a statement that said they had full confidence in his leadership. Sexton will stay through the end of his tenure, which ends this spring.

Christine Harrington, a politics professor who was the chair of the the Faculty Senators Council Governance Committee at NYU at the time, said votes of no confidence are critical in holding administrations accountable.

She referenced violations of shared governance and the increasing corporatization of higher education as catalysts behind no confidence votes across the nation.

“Really, underneath this all … was a violation of shared governance — the principles and policies that govern universities where they operate as tripartite political units with the administration, board of trustees and the faculty and students,” Harrington said.

At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the Undergraduate Student Government Association held its own vote of no confidence this past January against president Ray Watts, in addition to faculty votes.

USGA President Garrett Stephens said the vote became necessary following what he calls broken trust between the students and their president. After rumors that their football program was being cut, student representatives approached Watts and asked if this was true. He assured them no action was being taken. However, two days later Watts announced the cut to the program.

“That caught everyone off guard,” Stephens said. “A lot of that trust was broken between the student government and the administration. We weren’t consulted. We weren’t talked to.”

Following this incident, the student senate drafted a resolution, and senators unanimously voted no confidence in Watts, but a campuswide vote was not held. Stephens said student votes of no confidence are just as important as faculty votes because they can put pressure on the administration and have the student voices heard in the decision-making process.

Despite the votes against them, Watts and Sexton have both remained in office. Rochon has also said he has no plans to leave the college at this time.