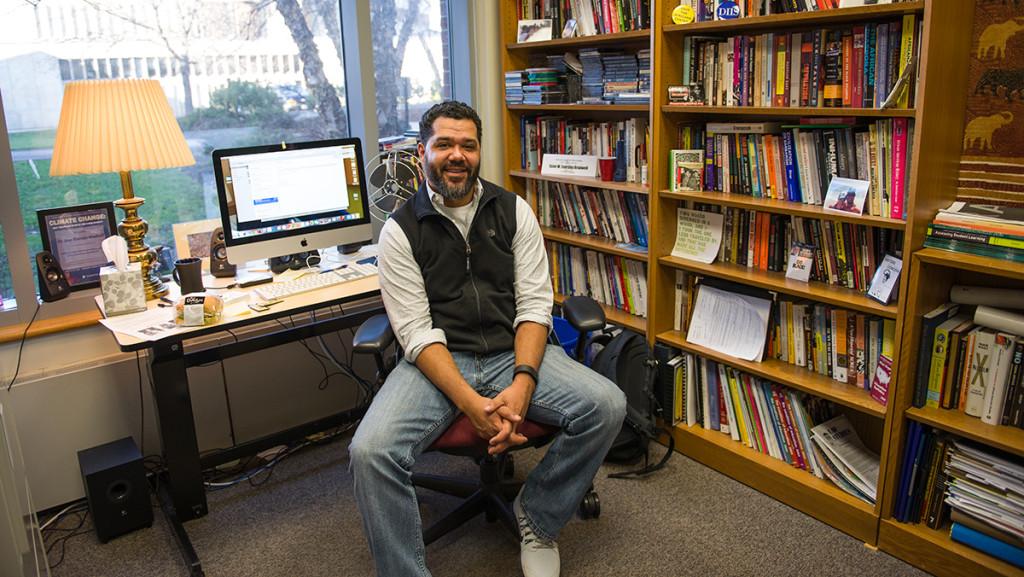

Sean Eversley Bradwell, assistant professor in the Center for the Study of Culture, Race and Ethnicity, has a background of study in policy analysis and management, with a particular area of interest in the educational experience of marginalized students.

Eversley Bradwell recently published an op-ed in The Root, titled “Do the Math on #AllLivesMatter and it Equals White Supremacy,” which examines the problems with the “All Lives Matter” slogan that emerged in response to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Senior Writer Sabrina Knight sat down with Eversley Bradwell to speak about Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy, today’s higher education climate and the recent unrest on college campuses across the country.

Sabrina Knight: What part of MLK’s work and legacy is still most relevant to our society today?

Sean Eversley Bradwell: Prior to Dr. King’s assassination, he was focused on what he called the giant triplets of racism, poverty and warfare. It would be hard for us to say those still aren’t pressing issues in 2016. We may add some others — homophobia, sexism, patriarchy — but there is no question that we still have a great deal of work to do around forms of racism, around warfare and around our economic injustice.

SK: What part of MLK’s work remains unfinished today?

SEB: Those, the giant triplets, without question, remain unfinished, but Dr. King was also trying to work toward two additional issues, if we study his work. One is a radical revolution of values to move away from a thing-oriented society to a people-oriented society, and I think we have a long way to go in that way, so we can do well to think about a radical revolution of values. And number two, Dr. King was trying to work along with his comrades toward a beloved community. Given what we’ve experienced on this campus around student reports of microaggressions and noninclusivity, there is a great deal of promise in trying to work toward a beloved community.

SK: In what ways do you think MLK’s legacy has shaped today’s higher education climate?

SEB: Without question, access. If we have 22 percent of the incoming class being ALANA students or identify as being ALANA students — and one of the things Dr. King was trying to do was make sure folks of color had access to higher education, to jobs, to housing — there is no doubt that we are experiencing some of the benefits of that movement to expand access to higher education to all students.

SK: Do you see any parallels between the recent unrest on college campuses across the country and the movement that MLK led?

SEB: And I see connections between movements that came before Dr. King as well. There is a long genealogy of the black radical tradition, so on this campus is a continuation of that long genealogy. In large parts, the civil rights movement was extremely effective but as we know, did not end racism, and so to think that our students wouldn’t still be protesting against racism, while it exists, again would be to not understand history completely.

SK: What are the differences between now and then?

SEB: Time folds back on itself. We are then. We’re in it.

SK: What do you think is the best way for students to get involved with institutional change?

SEB: One is to pay attention. Two would be to engage in conversation and dialogue, and that means reading some things, watching some films, sometimes being uncomfortable. And three would be to realize as a community we’re only going to strengthen our ties and become a much more inclusive community if we’re all sitting at the table having some conversations together.

SK: What are your thoughts on students’ participating in the MLK Day of Service to honor his legacy?

SEB: In CSCRE, we get to work closely with the Office of Student Engagement and Multicultural Affairs, and I think the day of service is a phenomenal event. What I really appreciate about OSEMA’s approach is they are really trying to get students to realize that a singular day is not the end–all to be–all — in fact, we want to create a culture of service, not a day of service.