Rebecca Plante, an associate professor of sociology at Ithaca College, used to give her students trigger warnings verbally before teaching coursework about sexual violence in her Sociology of Sexualities class.

“I had no way of knowing who in my class maybe had survived rape, had been subjected to some kind of sexual assault, who maybe had been subjected to something they had forgotten about,” Plante said.

But Plante had not anticipated how many students would tell her they could not do much of the controversial coursework because of past trauma they had suffered. So, about five years ago she decided to stop teaching about sexual violence altogether because it became almost impossible for her to accommodate all of her students’ needs. Her class still discusses the “social construction of gender, violence, power and sexualities,” Plante said, but she does feel the absence of the controversial material is a disservice to the course.

A national debate over whether trigger warnings should be used in the classroom, and how to deal with situations like Plante’s, has become prominent in higher education. Conversation about trigger warnings in the classroom began around 2013 when bloggers were regularly using them in their content, and then teachers picked up the practice. The Oxford Dictionary defines a trigger warning as “ statement at the start of a piece of writing, video, etc., alerting the reader or viewer to the fact that it contains potentially distressing material.”

Most recently, the debate swelled following a letter issued by the University of Chicago that said the institution does not condone intellectual safe spaces nor trigger warnings because they view them as a form of censorship of “rigorous debate, discussion, and even disagreement.”

The letter stated, “Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.”

Professors nationwide, and at Ithaca College, are unclear about how to protect students from trauma while also challenging them intellectually.

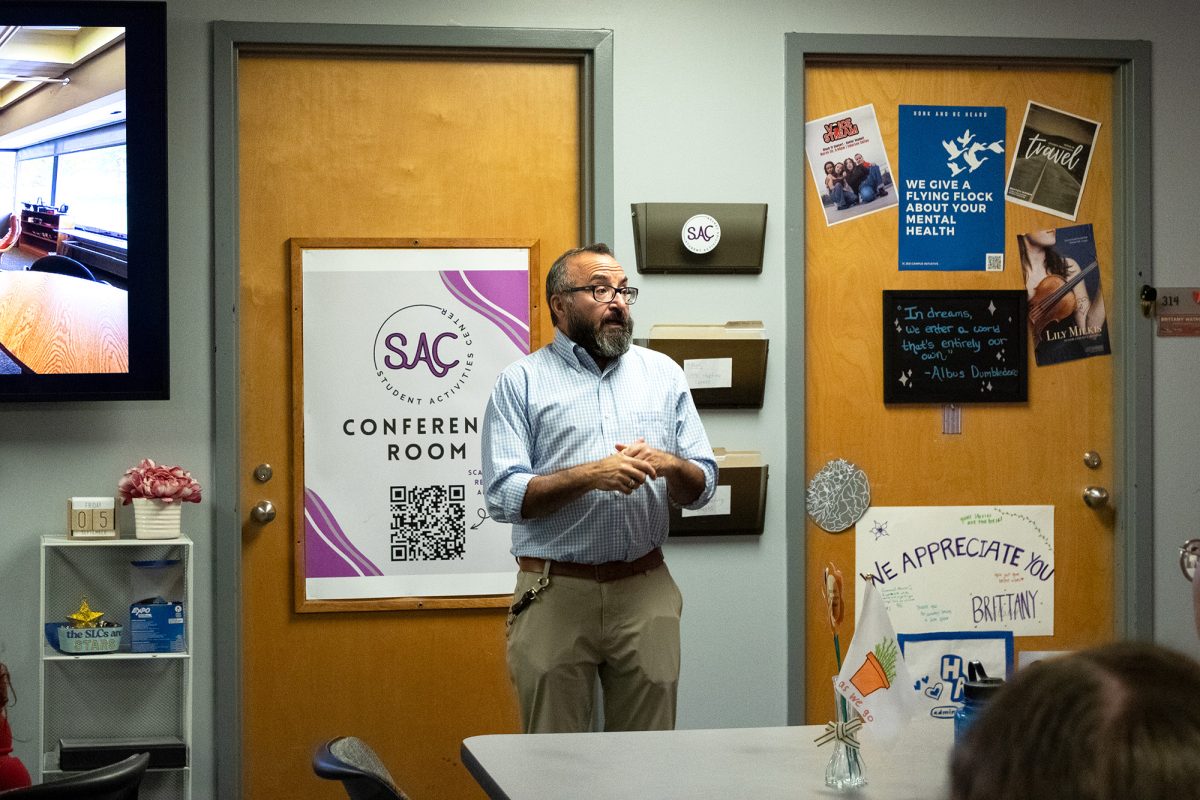

Tom Swensen, chairman of the Faculty Council, said the University of Chicago’s letter sparked a debate in an online discussion through Sakai among faculty members at the college about how trigger warnings should be used in class. He estimated about 10 percent of faculty were actively discussing their views on the issue online, and that they ultimately came to the consensus that it should be up to individual professors to decide on how to use them in their classrooms.

While the college does not have a policy on trigger warnings, the Student Code of Conduct for the college states: “Students are responsible for learning the content of courses of study but have the right to take reasoned exception to the data or views offered in the classroom. … Students have the right to expect a conscientious effort from faculty.”

Tiffani Ziemann, the Title IX coordinator at the college, said she believes the University of Chicago’s letter represents what she sees as a misconception about trigger warnings: that they are used to coddle students.

“I think when they are used well, it actually creates the opportunity for people to be more engaged and conversationed [sic] and feel more comfortable, because they know what they’re getting into,” she said.

Freshman Antonio Mims said he feels trigger warnings, safe spaces and free speech can coexist on a college campus.

“At all costs, people should at least be able to feel safe in their classroom environment,” Mims said. “I feel a lot of teachers view it as a special accommodation that is not necessary, but if you’re possibly going to cause trauma to a few of your students, then I feel like it’s worth it.”

Senior Alexandra Nicopoulos said she took a musical theater history class where her professor used a trigger warning before a lecture that included conversation about racial slurs. Nicopoulos said she agrees with the use of trigger warnings because they allow people to learn more comfortably.

“He said, ‘I hope I don’t offend anyone, but in order to explain history, I have to use specific racial slurs like black-face,’” she said. “We can’t predict what people have gone through in their lives.”

However, senior David Heffernan, president of the Young Americans for Liberty club, said he believes trigger warnings stifle education. He said people who are made uncomfortable by a certain subject should learn from the topic rather than hide from it because it may be distressing. He said he thinks people who have been seriously traumatized by a topic should reach out to a professor themselves to address the issue.

“If you have been severely impacted by one of those topics, then yes, that’s a conversation you need to have — maybe even think about dropping the course,” he said. “However, I do not condone people who wish to avoid a topic simply because it bothers them. … If you’re … listening to the same things you already know, you’re not learning.”

Out of 800 professors from colleges and universities who participated in an NPR Ed survey, about half said they have used trigger warnings in their classrooms. The survey also found that 86 percent of respondents knew what a trigger warning was and 56 percent said they knew of colleagues who used them. However, only 1.8 percent of professors said their institution has a specific policy on trigger warnings.

A group of about 150 faculty members at the University of Chicago wrote a letter to the freshman class on Sept. 13 in response to the University of Chicago administration’s letter. They stated that though the faculty have differing opinions among them on trigger warnings and safe spaces, discussion about these topics should always be encouraged. Not being able to talk about trigger warnings, they wrote, inhibits free speech.

Maggie Loughran, editor in chief of the Chicago Maroon, the student newspaper at the University of Chicago, said she thinks the letter to freshmen represented the position the university has always taken on free speech. The controversy, she said, came from the way in which she feels the letter trivialized the issue — putting the phrases safe spaces and trigger warnings in quotes — and showed the administration’s misunderstanding of the issue, angering many students and faculty.

“Whereas safe spaces and trigger warnings were sort of on the backburner last year, … now, students are going to be calling for them, and faculty who disagree will be using them and kind of challenging the administration,” she said.

Joan Bertin, executive director of the NCAC, said she thinks this has become a heated debate in recent years because millennials don’t understand how trigger warnings create censorship. Bertin, an advocate against trigger warnings, said professors see students’ demands for trigger warnings in the classroom as a way to avoid dissenting opinions — something the older generation has fought hard to voice.

“Trigger warnings also define specific content as ‘sensitive,’ although we know that people respond very differently to material,” Bertin said.

Some professors at the college, including Michael Smith, associate professor in the Department of History, let students know of sensitive material in the course but do not think of their actions as trigger warnings.

“At the beginning of the semester, I will say, ‘Look, we’re going to be studying U.S. history since the Civil War,’” Smith said. “‘There are lots of difficult things that happened in U.S history — there are lynchings and wars and violence — and that’s part of history, unfortunately, but that’s going to be part of this course.’”

Like Smith, Carlos Figueroa, assistant professor in the Department of Politics, said he provides a written statement to students before teaching controversial material, which he said many other professors do, too. Figueroa said he does not classify this as a trigger warning but thinks of it instead as a courtesy to students.

While Figueroa and Smith said they are willing to be flexible with students who do not want to participate, they tell their students that the sensitive material is important in learning about a particular subject.

“I also add that it’s part of the educational process,” Figueroa said. “This is why I’m including it in the first place. I’m not including something to offend someone. It’s to strike up conversation and debate about a particular theme maybe we need to get through.”

Though trigger warnings have changed the way Plante teaches her Sociology of Sexualities course, she said she still supports their use. Throughout her teaching career, she said, she has struggled to find a balance between being respectful and sensitive to students without sacrificing people’s opportunity to learn.

“At the end of the day, do as little harm as possible to our students,” she said. “What we do do is in the service of helping students become better people, better thinkers, better human beings.”