Editor’s Note: This article is a corrected version of an earlier version of this article that ran yesterday.

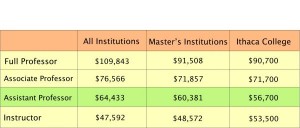

Assistant professors at Ithaca College are making $7,733 less than assistant professors on average nationwide, and $3,681 less than the average at other master’s-granting institutions.

A study released by the Chronicle of Higher Education on April 16 found that about 60 percent of the assistant professors at master’s institutions are paid more than assistant professors at the college. On average, full and associate professors make $19,143 and $4,866 less, respectively, than full and associate professors nationally, but are close to their counterparts at master’s institutions at $90,700 and $71,700.

Mark Coldren, associate vice president of human resources, said pay varies widely among faculty. He said professors, unlike college staff members who are paid in salary bands with definite ranges, earn different amounts based on school size, the college’s definitions of titles such as “associate” and “assistant” professor — titles with meanings that often vary by school — and on local costs of living, which are lower in Ithaca than in metropolitan locations.

“If we have somebody that’s called a ‘groundsperson’ and that’s a job that 20 people hold and it’s similar, they’ll all have the same job description and they’ll all be in the same band,” Coldren said. “They might be doing different things, but it’s all within that job description. The hard part is on the faculty side — we don’t necessarily have a faculty job description. They could teach a lot of different things.”

Coldren said determining the actual meaning of the $7,000 salary difference for assistant professors at the college is nearly impossible.

“If you want to make some kind of conclusion that says Ithaca College associate professors make, oh, $70,000 a year, you’re going to have a wide range there,” Coldren said. “What you have are some averages, and you can draw some conclusions if you want to, but I don’t know how I can compare that.”

Kathleen Rountree, provost and vice president of academic affairs, said the college’s salaries are neither strong nor particularly weak compared to the national average.

“I’m not sure being in the middle of the pack is a bad place to be,” Rountree said. “Some of the schools that are higher have different programmatic mixes. If a [college] has a law school, for example, their salaries are going to look higher because they have those high law school salaries to bring them up.”

Coldren said the college hasn’t had many problems hiring lecturers or adjunct professors for lower-paying positions.

“There’s usually discussion — if they have different salary expectations, they might say, ‘Hey, that’s too low,’ and walk away,” Coldren said. “But mostly, we’re able to identify lecturers or course-by- course instructors. I’m not going to say it’s easy, but it’s done pretty straightforwardly.”

Interim Business Dean Mark Cordano said the college is in a “micro-market,” or small setting in which potential faculty members who cannot find a job at Cornell will come to Ithaca College looking for work.

“Cornell’s been downsizing because of what they’ve been running into as a budget crunch, so that means they’re hiring less adjuncts,” Cordano said. “For the past few years it’s been a lot easier for us, whereas four or five years ago, it was a lot harder.”

Rountree said her office has made an effort to raise salaries and keep them at competitive levels.

“We brought up the bottom [for assistant professors],” Rountree said. “When I arrived at Ithaca, the starting offer for an assistant professor was $42,000, and one of the first things I did was raise that to $50,000. We’ve made a couple of good steps in moving forward.”

The national average rate of salary increase for college and university faculty for the 2009-10 academic year is 1.2 percent, the lowest rate in 50 years, according to the Chronicle. In 2009-10, Ithaca College salaries were frozen, but later, the board of trustees approved a one-time compensation program for faculty and staff in response to a projected $3.3 million surplus created by the class of 2013.

A 3 percent pool for salary raises, which is the amount of money budgeted for increases in each school and department, will be available for the 2010-11 academic year. Carl Sgrecci, vice president of finance and

administration, said 2.5 percent of that pool will be distributed across the board and the remaining 0.5 percent will be distributed based on good performance reviews or exceptional accomplishments.

Cordano said the additional merit increase could range anywhere from 0.2 to 0.7 percent.

“It can actually go above 3 percent,” Cordano said. “If someone only ends up getting 2.5 percent, that means there’s some additional fraction left to give to other people. [But] anything above 2.5 is based on individual performance.”

Stan Seltzer, Faculty Council chair and chair of the mathematics department, said next year’s 3 percent increase will benefit professors because it will add to their salary bases. He said humanities and sciences salaries are not high, but many professors are still satisfied.

“Nobody goes into [math] with the notion that they’re going to make a lot of money,” Seltzer said. “You go in with your eyes open. People do this because they think it’s important work and they actually enjoy doing it.”

Coldren said business faculty are among the highest paid on campus, while humanities faculty tend to receive lower salaries.

Tatiana Patrone, assistant professor of philosophy and religion, said she is satisfied with next year’s salary increase. She said salaries at the college are fair when other circumstances are taken into account.

“I think that the pay at Ithaca that I have is slightly less than some places and slightly higher than other places,” Patrone said. “But I think that’s less compared to [other] places for geographic reasons. At some institutions, the starting salary would be higher because the cost of living is so much higher.”