Above average is the new average for grading in higher education. While mathematically impossible, this situation is a reality at most colleges and universities across the country.

The distribution of grades now swings heavily in favor of As and Bs, and GPAs continue to rise. This grade inflation has been the topic of heated debate in higher education for decades, causing many to question student culture and ability, and what it means to get an A in 2011.

Nationwide, the average GPA at both private and public institutions has risen. According to data from 80 schools compiled by Stuart Rojstaczer, a former geophysics professor at Duke University who has researched grading trends for journals and his website, Gradeinflation.com, the average GPA has risen from 2.93 in the 1991-92 academic year to 3.11 in the 2006-07 year. Of more than 130 colleges and universities for which he has the most recent data, more than 43 percent of all grades are As on average.

“A is the most common grade now by a lot,” he said. “The gap between [As and Bs] keeps rising. Professors keep grading easier and easier every year.”

ITHACA WITHHOLDS INFORMATION

With national statistics for average GPAs and grades on the rise, it’s possible this trend persists at Ithaca College.

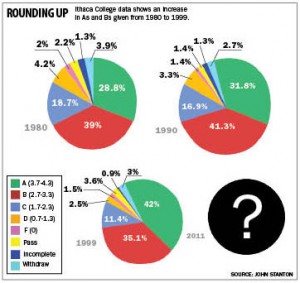

In 1999, the number of As awarded at Ithaca College had risen by 13 percent in 19 years to 42 percent of all grades. Today, the college refuses to release any data about the distribution of grades at the college.

Carol Henderson, associate provost for academic policy and administration, said the college will not release specific data on grade distribution at the college since 1999 but said she did not believe grade inflation to be a problem at the college. Registrar Brian Scholten said he did not have applicable data or a basis for comparison with past data.

Yet, past college administrations have been more forthcoming in providing data on the distribution of grades at the college. In 1980, then-registrar John Stanton began tracking grade distribution at the college out of personal interest. Under President Peggy Williams, Stanton released the data to The Ithacan in 1999.

From his research, Stanton found that in 1980, the percentage of As was 28.8, Bs was 39 percent and Cs was 18.7 percent. All other grades made up 13.6 percent of grades. By 1999, As rose to 42 percent, Bs and Cs fell to 35.1 and 11. 4 percent, respectively, and all other grades fell to 11.5 percent.

“I like to think, to some degree, that we have a better-prepared student body than we had 20 years ago,” he said in 1999. “There’s no backing to that. Yes our SAT scores are better than they were 20 years ago on average, but are they that much better? I don’t think so.”

Henderson declined to provide the exact average GPA for the college. She said the college’s average GPA has remained consistent over the past six years, and the college’s data was “significantly underneath” other institutions.

According to Rojstaczer’s data, in 1980, the college’s average GPA was 2.95. In 1990, it rose to 3.04, and in 1999, the most recent data, it rose to 3.23. Rojstaczer calculated these averages from the data Stanton compiled and said he has been unable to get recent data.

In comparison to four institutions that are members of The New American Colleges & Universities, a consortium of 20 institutions with which the college compares itself, the college’s 1999 GPA was higher than all of its most recent figures on Gradeinflation.com. The institutions with available data included Drury University (3.20, 2006), Elon University (3.16, 2008), Hampden-Sydney College (2.78, 2008) and Butler University (2.35, 2007). The college also ranked higher than Syracuse University’s 2002 GPA of 3.15.

Anecdotally, faculty members have said grade inflation at the college persists.

Stan Seltzer, associate professor of mathematics and chair of Faculty Council, said he looked at data on grades in the School of Humanities and Sciences a few semesters ago, and though he didn’t remember the specifics, he was surprised by the results.

“They were a little higher than I would have expected, and I had the impression grades were what I would consider relatively high anyway,” he said.

Nancy Cornwell, chair of the television-radio department, said as a department chair, she often deals with what grades are given.

“I don’t know what it says when all of our students are above average,” she said. “It’s one thing to bring to the freshman class, all above average students, because we’re a selective school. But then they’re all above average students here, so what’s the new average?”

CULTURAL SHIFTS

Until the 1960s and early 1970s, Rojstaczer said students were “acolytes” to their professors and went to college to gain knowledge from experts. Beginning in the 1980s, tuition began to rise, student evaluations gained importance, and students’ and parents’ attitudes changed.

“Professors and deans have capitulated to this view so they view the student and the parent as consumers, and they want to please them,” he said.

Many also argue that students expect to earn high grades.

According to a study by researchers at the University of California, Irvine, titled, “Self-Entitled College Students: Contributions of Personality, Parenting, and Motivational Factors,” 40 percent of student respondents said they deserved a B for completing required course readings, and a third said they expected a B just for attending class.

Jack Powers, assistant professor of television-radio, said the expectation of good grades starts in high school. When students come to college, they anticipate that will continue.

“Sometimes they take classes in college and for the first time they’re like, ‘What do you mean I’m getting a D? … How’s that possible? I always get As,’” he said.

SAT SCORES

According to the College Board, SAT “score changes are slight over time.” Since 1972, the mean critical reading score is down 28 points, and the mean mathematics score is up seven.

Though she declined to provide the specific data on the college’s average GPA, Henderson said the rise in GPA has mirrored the rise in the college’s SAT scores.

“Many institutions have had rising GPAs but flat SAT scores,” she said. “In the case of Ithaca College, the GPA rise is mirroring the rise in SAT scores. In other words, it’s not necessarily a grade inflation problem. It’s the SAT scores, and hence the student quality is going up at the same rate as the GPA.”

In their article, “The Falling Time Cost of College,” Mindy Marks, assistant professor of economics at the University of California Riverside, and Philip Babcock, assistant professor of economics at the University of California Santa Barbara, found that students in 2004 allotted an average of 26-28 hours per week to class and studying. In 1961, students allocated 40 hours per week.

Michael Trotti, associate professor of history, said the standard in higher education is that students work twice as much outside class as they do in. He said the average number of hours students at the college study outside the classroom is troubling.

“It’s clear whenever I’ve asked the question … of how many hours are you working, that the average student at Ithaca College in my classes at least, is not doing that much,” he said. “That’s something that’s of concern as a professor and a part of the Ithaca college community. There’s something in the culture of the school, or in the student body anyway, that’s not supporting the appropriate rigor.

Rojstaczer said the national stagnancy in SAT scores calls into question whether this is a reasonable explanation for a rise in grades nationwide.

“It’s not true,” he said. “You can expect a little bit of a rise in student rise and quality, but the levels of grade rises do not match the increase in student qualities.”

ROLE OF EVALUATIONS

Barmak Nassirian, associate executive director of the American Association of College Registrars and Admissions Officers, said one reason for the rise in grades is the role of student evaluations.

“It automatically incentivizes faculty to be more lenient, to be more popular,” he said. “This is not a cynical move, it’s in the background of the decision process, and it’s a very human reaction to the very notion of being rated.”

Cornwell said the increasing reliance on course evaluations for teacher evaluation and tenure promotion is problematic. She said faculty at the college, both on a tenure track and on contract, feel “enormous pressure” to get good evaluations, and high grades are just one of the ways to do this.

“Teachers are under pressure to entertain, as well as convey information, and they’re measured on how well students embrace them,” she said. “There’s pressure to make sure students are happy. Good grades make students happy.”

Fred Wilcox, associate professor of writing, said the college emphasizes student evaluations for professors going up for tenure.

“They learn right away that these evaluations are very important to the college and that without pretty much stunning, really good evaluations, you’re not going to get tenure at Ithaca College,” Wilcox said. “Professors are held hostage by evaluations and that might make one more inclined to give students better grades than they might deserve.”

LASTING EFFECTS

Trotti said he finds the prevalence of grade inflation in college to be problematic.

“It seems to me that it undercuts the legitimacy of our programs and our degrees,” he said. “You never want somebody to leave because there’s not enough rigor. If this kept going, I would be concerned about the effect on student learning and on the school as well.”

Rojstaczer said because the culture of higher education emphasizes loosening up grades to attract more students, it would be difficult to reverse grade inflation. He said enrollments would suffer, budgets would decrease and teacher evaluations would be poor.

“What it means is that we’re discounting the value of an undergraduate education in terms of its ability to provide critical skills like reading, writing, analytical thought processing and critical thinking,” he said. “We’re saying that college is more of a very expensive summer camp.”

Wilcox said the administration should release data on the distribution of grades at the college.

“Why wouldn’t they release it?” he said. “I don’t see any reason not to. It’s not government confidential or state secrets.”