Thirty or so students form a haphazard circle of desks, and a seeing-eye dog yawns in the corner before shifting attention to the bone she’s been working on all week. Josette the black lab has become a sort of mascot for the tense silence that occasionally falls over the classroom. Silence is the sound of her jaw closing firmly around the bone. Crunch. Scrape. Pant. Slobber.

It’s a grotesquely cheerful backdrop to discussions that routinely revolve around grave exhumations, rape and mass slaughter.

Junior Laura St. John often slings her backpack over her shoulder and walks out of the room, sighing, “… if it wasn’t for that dog, this class would make me go nuts.”

The images of trauma themselves don’t bother Laura as much as their subtext. She leaves Associate Professor Peyi Soyinka-Airewele’s Politics of Memory course asking questions she’s not prepared to answer, silenced by an internal conflict, mesmerized by the complexity of human interactions. Thinking about it keeps her up at night.

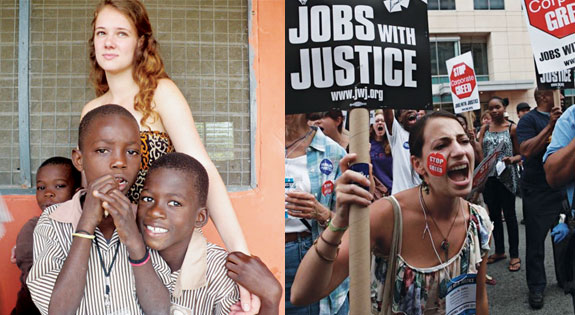

Last spring around this time, Laura was one of the loudest voices of protest on campus, fists clenched, feet stomping and voice raised for her friends and co-workers — dining hall employees without a living wage and without enough money to feed their families. She pokes fun at herself now.

“Oh, back in my activist days …”

Senior Morgan Milazzo knows the joke well — the fine line separating then from now. She sits at the front of the room beside Josette in class with legs crossed, writing furiously in a notebook.

About two years ago, Morgan sat in a smaller classroom, which was dizzyingly hot and thick with the smell of petrol. She was responsible for keeping orphans from dipping their noses into Dixie cups of gasoline, props in a lesson about water.

“Water has no smell, water has no smell, water has no smell …”

The children repeated the phrase over and over again. It was Morgan’s only teaching lesson and her first day teaching at an orphanage in Ghana — the country one professor referred to as “Africa for beginners.”

“I wanted to be one of those people who saves the world and saves Africa,” she laughs, embarrassed. “I used to say that. I was a gem freshman year.”

Morgan and Laura went into volunteering and activism thinking they knew what they were doing, but they’ve stumbled across a long list of practical and philosophical questions they hadn’t bargained for. They occupy the tenuous space between past and present, intention and result, personal and political.

Welcome to Ghana

Morgan arrived at the airport in Accra on a summer night in June. Her eyes searched, glancing between holes in the crowd of Ghanaian families who she imagined were on their way home. Morgan was farther from home than she’d ever been. Her eyes finally fell on a man holding a piece of paper with her name written across it.

“Morgan?” he asked.

“Hi, I’m Morgan.”

“Welcome to Ghana.”

He took her bag and walked toward an unmarked van. It was about midnight, warm and dark. There was another man in the backseat, and the two talked in a language Morgan didn’t understand.

As the van wound swiftly through jungle dirt roads, African drumming vibrated her seat. The driver had no qualms about digging in the back for a new cassette when he got bored with the rhythm, veering into what would be opposing traffic, had there been any. After about three hours they dropped Morgan off at a hotel where the room had a single bare lightbulb hanging from the ceiling. It wasn’t until the sun rose the next morning that she realized the orphanage was about 100 yards down the road.

“Welcome to Ghana.” That’s the only thing the man ever said.

After the first couple of days, Morgan settled into life at the orphanage. She was surprised by how normal it all was — not quite the major adjustment she had imagined. The kids loved her. A little boy named Prince literally attached himself to her hip for the first couple of weeks. Sometimes he called her “mom.”

When the time came to say goodbye two months later, the children crowded around her feet.

“When are you coming back? When are you bringing us to America?” they asked.

She told them the truth.

“I’m 19. I’m not bringing you guys back to America with me.”

At first, returning to the U.S. felt like waking up from a dream. It wasn’t until recently that Morgan began to reconcile her experience in Ghana. The kids smile back at her from pictures on her bedroom wall. Above the collage, a quote reads, “We don’t give because of their need, we give because of our need to live in a just world.”

Taste of home

The gas stove flickers on. Laura methodically chops onions and scrapes them into the pan, throws in some basil and a dash of olive oil. She mixes in the tomatoes with a wooden spoon. She’s learned what to add when the consistency or color isn’t just right. The aroma settles in the air, subtle and sweet like memories of her family.

Sauce is Laura’s favorite thing to cook, and naturally she volunteered to serve her roommates their first meal of 2012. It wasn’t until

after the plates had been served and cleaned — all without turning off the TV — that Laura became painfully aware of the fact that still lingered in the air with the smell of garlic. She missed the boisterous laughing and talking of what she describes as her stereotypical, loud Italian family.

Last summer, as an intern at the Tompkins County Workers’ Center, Laura was tasked with interviewing locals about what kept them up at night. Not surprisingly, she met Don, an Ithaca resident, in the same way she met many others she interviewed — across the dinner table, sharing a meal at Loaves and Fishes of Tompkins County.

Laura remembers the way his laugh seemed jolly and sad at the same time. He told her about the family that had left him and would not return his calls, how alone he felt. She didn’t just know how he was feeling, she understood. She looked up from her notebook and stopped taking notes. When he left, she hugged him goodbye.

“All of the previous interviews had been to satisfy the questions that have been given to me and this didn’t really stick to that format,” she said. “This was just like a conversation that helped me. I felt like the roles had been reversed or shared in a way.”

After meeting Don, Laura realized the sort of interactions with the potential to really make an impression can’t come from screaming in the street.

Voice of doubt

In her years teaching at Ithaca College, Soyinka-Airewele has seen many students confronting ambiguity and occupying the spaces outside the polarized territories that society deems legitimate. The questions they ask have the power to shatter an individual completely. She’s seen some of her brightest students give up on change and drop out of college.

“What happens to them is they kind of go through a self-immolation,” she says. “They almost envy those who are more superficial. Superficial people are very lucky in this world. They just do it, you know? They don’t have the soul-searching dilemma, they don’t have the angst … ”

Morgan sometimes wishes she could just say “Oh, awesome” when she meets students who cling to dreams of building a school in Africa or hears about concerts to raise money for child slaves. Instead she can’t help but remember the boy she met in Ghana whose father sold him into forced labor.

“Does it really matter to him that kids in Ithaca know that there’s slaves out there when his father sold him into slavery?” she wonders. “How is raising awareness actually helping?”

In Ghana, Morgan saw the institution with all its cracks. And with those flaws exposed, she’s come face to face with her own limitations. Still, she’s planning a career in international development when she graduates.

Laura is confronting a similar tension as she begins to plan for the “local-organic, pay-as-you-can, carbon-footprint-free bakery” she wants to open next spring.

She was so into the Labor Initiative in Promoting Solidarity’s living wage campaign last spring. It was a battle that felt natural for Laura, who stands up for the treatment of blue-collar workers as if they were family. Injustices toward dining service workers sting like the injustices she’s seen her father, a pipefitter, encounter at his work. Still, she admits she won’t be able to pay her bakery workers a living wage.

“I can’t pay a living wage to start,” she laughs. “I won’t even receive a living wage. It’s a lot of money if you’re a small business. And it kind of cripples small businesses, so you have to look at that side of it too.”

Don Austin, assistant director of community service and leadership development at the college, said it’s rare to find someone willing to own up to this uncertainty or admit to contradictions.

“They’re all going to tell you they’ve got it figured out,” he said. “But we’re all learning as we go.”

Naeem Inayatullah, professor of politics, strives to support and cultivate the voice of doubt in his students. He said self-exploration in this way is often the root motivation behind activism.

“These students and these volunteers or professionals — they all think that what they’re doing is about aid, but it’s not,” he says. ”What they’re really doing is about an encounter — encounter primarily with one’s own doubts.”

Without recognizing these doubts, Inaytullah said, students interested in activism and community development run the risk of doing more harm than good.

“Someone who is very confident of what they’re doing in terms of volunteerism or anything — chances are extremely good that they’re going to do a lot of harm,” he says. “Someone who is in the middle of vulnerability is aware of the single most important thing, which is their own humility in the face of incredible complexity.”

Morgan and Laura’s experiences chronicle the crisis of identity that sometimes arises when the time is taken to question the motivations driving their work and consider the implications their service may have.

It’s a narrative Soyinka-Airewele sometimes hears in classroom silences and one that manifests itself in the margins of student essays. Their uncertainty articulates itself with silence.

Josette, the seeing-eye dog, sits in the corner and gnaws on her bone.