It started with a group of high school friends in Nahant, Mass., with a net built out of sticks and a 99-cent rubber ball. Twenty-eight years and 350 miles later, a schoolyard game called pinkyball has made its way to Ithaca.

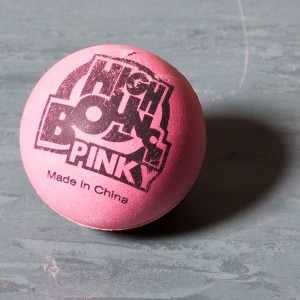

Pinkyball, a combination of handball, lacrosse and soccer, has laid dormant for decades, being played only in a small high school in Massachusetts. This December, the sport will be introduced on the collegiate level when the college hosts its first intramural pinkyball tournament.

Junior Reeve Moir, pinkyball’s local ambassador, stood in front of six students dressed in casual athletic clothes in October on the Mondo Gym Floor in the Fitness Center to facilitate the college’s inaugural game of pinkyball. The players formed into two teams, The Short Guys and The Kentucky Gentlemen, and Moir led a short informational session before the fast-paced game kicked into gear.

Moir described the basic move of pinkyball as a type of air juggle, where players try to keep the ball alive with a series of palm slaps while moving up the court. Players are allowed to slap the ball five times before they have to shoot or pass the ball to a teammate. The player can also kick the ball when they run out of palm slaps. Players can incorporate moves from other sports, like indoor soccer, to kick the ball off the walls and advance the ball forward.

“The goal of the game is to score points by hitting it into the net, just like soccer or lacrosse,” he said.

Shots on goal are directed at a goalie armed with only a baseball glove. Teams feverishly push the ball up and down the court attempting to score a goal. When a goalie makes a save on a high-speed slapshot, he or she can throw, slap, kick or roll the ball out to a teammate, and the play continues.

Junior Lucas Knapp participated in the college’s inaugural game of pinkyball. He said the sport was easy to get involved with because it doesn’t require special athletic gear or any type of specific athletic skill.

“You just need your hands, your body, some shorts and a t-shirt and you get to run around and have fun with your friends,” Knapp said. “It’s really not about who wins or loses, it’s just about playing pinkyball.”

Knapp identified the process of dribbling and kicking such a tiny ball as the most difficult parts of pinkyball to learn. Despite the learning curve the players faced, Moir said pinkyball’s simplicity got everyone engaged quickly.

“Everybody got the rules down really quickly, and then we just played for a while,” Moir said. “It was an awesome time. Tons of fun.”

Even with a wide range of athletic abilities present in the exhibition game, the game was evenly matched and ended with a close score. Moir attributed this to the even playing field created by lack of player experience.

“I want to stress to people the fact that since it has never been played here, nobody will have a distinct advantage in it,” he said.

Until this year, people only played pinkyball at the Waring School in Beverly, Mass., where it was first invented. As a sports management major, Moir created a project that would have a lasting impact on the office of recreational sports in his fieldwork assignment. Moir, a Waring alumnus, said he decided to pitch an old high school favorite as an intramural tournament at the beginning of the semester.

To adapt pinkyball to the collegiate level, rules had to be formalized and designed for the resources available to the college while maintaining the integrity of the original game. Goals once made of sticks have been replaced by nets of metal and nylon. Games that used to start with a toss off a chimney now begin with a simple jump ball reminiscent of basketball.

Because of its newness and unconventional set of rules, pinkyball is considered a non-traditional sport. Scott Flickinger, program coordinator of recreational sports, said, non-traditional sports create a relaxed in-game atmosphere and are open to a larger range of participants. The last intramural sport that was introduced to the college was Ultimate Frisbee during the spring of 2008.

“What we look at is something that may attract people who aren’t interested in more traditional sports,” he said. “There’s a lot more of the casual athlete, and these non-traditional sports appeal to them.”

Another factor that Flickinger considers when looking at new intramural sports is the cost. Pinkyball utilizes equipment already available, such as floor hockey goals and baseball gloves, and the pinkyballs themselves are inexpensive.

Flickinger said the challenge with running it as an intramural sport is getting people to show up. He said he is hoping the appeal of a brand new sport will draw in players.

“I always want to do something that’s new,” he said. “There are individuals looking for alternative activities to some of the more social aspects of Thursday and Friday night. We try to provide that outlet for individuals looking for a positive, fun release in terms of physical, mental and emotional safety.”

Flickinger researched what other colleges’ intramural programs have been doing and he found that non-traditional sports have been successful elsewhere. He said he also looked into handball at other colleges because of its strong similarities to pinkyball.

“[Handball] has been pretty popular in a lot of schools, and I thought, [pinkyball] is nothing we have ever seen before here, and it is nothing anyone else has really ever seen outside of Ithaca College, so why not be the pioneer?” he said.

Sign-ups for the tournament, set for the weekend of Dec. 1, were recently opened up to the campus community after the trial game Oct. 7 was deemed a success by the department.

Knapp said the people that were watching from the balcony in the fitness center during the first game looked a little confused, but also intrigued. Based on his experience, Knapp said pinkyball would fit in line with some of the campus’ other quirky activities.

“We play Quidditch and have Humans vs. Zombies,” he said. “It’s not much of a stretch to have pinkyball in there too.”

Time will tell as to whether pinkyball will be successful at the college, but Moir and Flickinger said they hope the game will be a staple in intramural programming in the future. Flickinger said there are even tentative plans to make a pinkyball league next fall, depending on the success of the tournament this December. He said the adoption of this unconventional sport is a major step ahead for intramurals at the college.

“The future is going to be with non-traditional sports,” Flickinger said. “Everybody and anybody can play the traditional sports. But, every once in awhile somebody will say, ‘I want to try something new.’”