I could feel the humidity stick to my skin the second I stepped outside the airport. It clung to me, enveloping me in its warmth and welcoming me into a country that, for the past 54 years, was more or less closed off from the United States, roughly 90 miles away.

I had a very baseline knowledge of Cuba before traveling to the Latin American country. I knew Cuba was a socialist country. I knew who Fidel Castro was. I knew the country fiercely resisted colonial rule for hundreds of years to establish its own independence.

The first thing I noticed about Cuba was its cars, colorful and classic. I could not remember any car in the U.S. that looked even remotely similar to a Cuban car. They came in bright hues of green, pink, blue and purple. They came as classic Chevrolets and Fords, and some even came as Soviet-inspired box cars.

Celisa Calacal/The Ithacan

The cars themselves are emblematic of Cuban history as well as the stark contrast that exists between the West and Cuba. The popularity of classic cars in Cuba stems not from a desire to have them, but from economic circumstances. A ban established by Castro following the revolution and decades-old U.S. economic sanctions blocked foreign vehicle imports from entering Cuba. It was a series of political moves that has left Cuba with these old, classic cars and no access to their repair parts. However, in 2014, Cuba’s council of ministries and President Raul Castro lifted the Cuban restriction, opening up the vehicle market to its citizens. Of course, it is still difficult to detect this change, as classic cars still zip down Havana’s streets.

So when one of these cars breaks down, two options exist: Leave it in disrepair, or fix it. With no easy access to parts, most Americans would probably opt to throw the car in a junkyard, leaving it to rust in the sun. But most Cubans I saw were actively fixing these cars with any materials they had at their disposal. It’s an attitude of ingenuity and resourcefulness that has made these cars last for so many years.

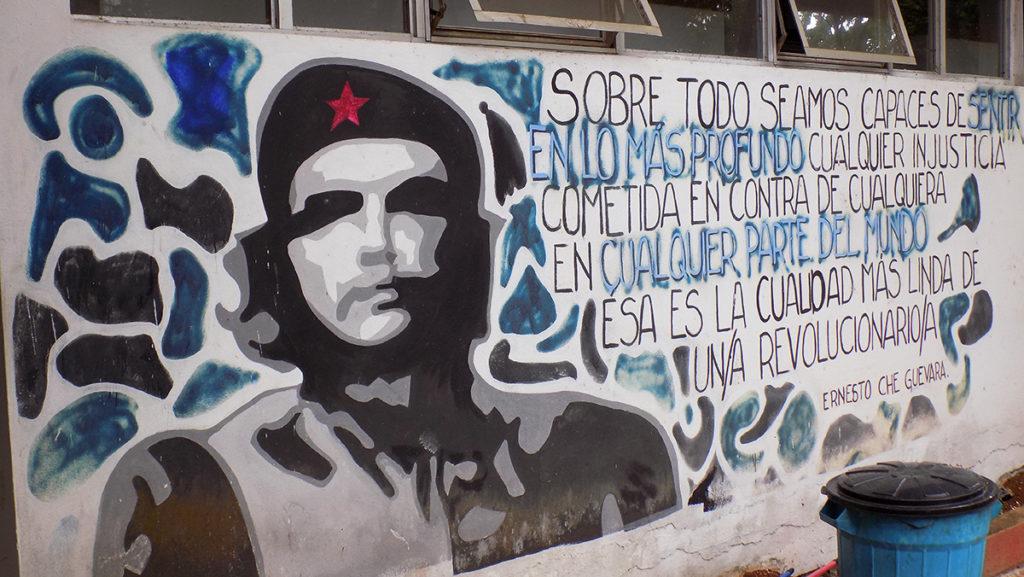

The second thing I noticed about Cuba was its billboards. And it wasn’t because they were splayed with flashy advertising type or provocative pictures. It was the messages. “Hasta la victoria siempre.” “Viva Cuba libre.” Accompanying many of these messages are pictures of Castro and Che Guevara, a Latin American revolutionary who was a key figure in Cuba’s revolutionary era and fought alongside Castro. These billboards convey political messages, many of which are doused with patriotism and national pride.

This sense of pride and patriotism isn’t just present on the billboards — it’s everywhere. This patriotism manifests itself in the many monuments across Havana: at the Plaza de la Revolución, the Museo de la Revolución, the statues dotting the Malecón that borders the sea-blue Gulf of Mexico. It was in the graffiti, displayed in colorful type across off-white walls: “Los CDR seguimos en combate,” “Es mejor entregar las armas, que combatir sin moral,” “Fieles a tu coraje y a tus ideas.” Even the tourist hotels in Havana were imbued with patriotism: The Habana Libre, originally planned as the Habana Hilton in 1958, became the headquarters of Castro and his army in 1959 during the Cuban Revolution. In 1960, when American hotels in Cuba became nationalized, the Habana Hilton was named the Habana Libre.

It is easy to tell that Cubans are very proud of their revolutionary history and their decades-long resistance against imperialist, capitalist and colonialist forces. Of course, one could easily argue that a similar kind of patriotism is present in every country. The U.S. has monuments across the country honoring the American Revolutionary War. We even have a holiday honoring the adoption of our esteemed Declaration of Independence on July 4.

But personally, I don’t feel much patriotism toward the U.S. Thinking about the Revolutionary War doesn’t instill a sense of pride in me as Cuba’s revolutionary era inspires in Cubans. In fact, I feel more pride for my family’s native Philippines than I do for the U.S. Perhaps it’s because, like Cuba and many other nations, the Philippines was also imperialized by both Spain and the U.S., leading the island nation to also fight for its independence.

So when I saw the monuments to Guevara, Castro and Cuban national hero and Latin American poet José Martí, I admired them. When I read about the different tactics the U.S. employed to end the Cuban revolution and assassinate Castro — which amounted to more than 600 failed attempts — I was enraged. The lengths the U.S. went to to squash a movement toward independence, one that was anti-capitalist and socialist in nature, is terrifying and sickening at the same time.

And when I heard the story of the Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine that sat by the Malecón, I cheered. Adorned with a bald eagle sitting atop a stone pillar, the monument was originally built by the U.S. in 1925 to commemorate those who died in the explosion of the USS Maine in 1898, the event that became the precursor to the Spanish-American War. Then in 1961, a group of Cubans removed the eagle, leaving the pillar standing barren like a large middle-finger to imperialist power.

Because of the political barricades and economic embargo between the U.S. and Cuba, the island nation may seem like a place frozen in time, with its abundance of classic cars and the general lack of internet connection. But Cuba is not so much stuck in time as it is a country constantly preserving its independence, all while ensuring its people receive their most basic needs.

During the week I was in Cuba, I felt a connection to the country and its people that is virtually nonexistent in the U.S. Perhaps it was the generous hospitality of the Cuban people I met that reminded me of Filipino hospitality. Or maybe it was simply the warm island weather or the array of tropical fruits I often long for.

While these aspects influenced my connection to Cuba, it was the country’s rich history that solidified this connection. It was the revolución and the fact that the country has never stopped fighting for its independence. It was the rejection of colonialism and rampant capitalism that makes Cuba stand in contrast to its imperialist neighbor.

Most of all, it is the fact that Cuba’s history is emblematic of the struggle many people of color around the world experience: the struggle for patria and for independence, of nation and of self. Cuba’s history in the past and present is the continued fight against colonialism, imperialism and white supremacy. It is about the quest for “libertad” — for freedom and true liberation. “Patria es humanidad.” Continued and constant resistance — that’s what it’s all about. “Hasta la victoria siempre.”

Translations:

“Hasta la victoria siempre.” — Ever onward toward victory.

“Viva Cuba libre.” — Long live free Cuba.

“Los CDR seguimos en combate.” — The Committees for the Defense of Revolution continue in combat.

“Es mejor entregar las armas, que combatir sin moral.” — It is better to surrender the weapons than fight without morals.

“Fieles a tu coraje y a tus ideas.” — Faithful to your courage and your ideas.

“Patria es humanidad.” — Homeland is humanity.