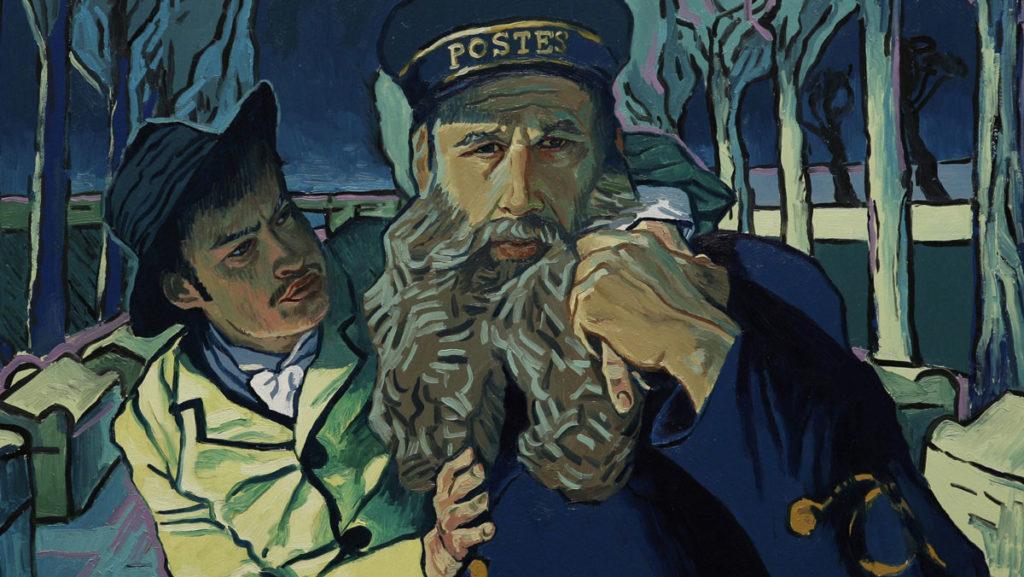

In “Loving Vincent,” every frame is literally a painting.

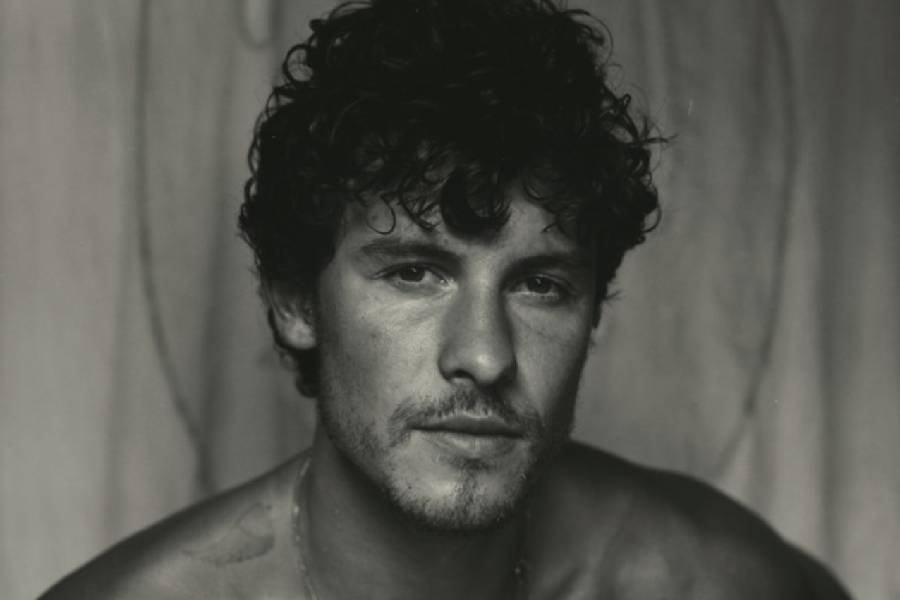

The film follows Armand Roulin (Douglass Boothe), the son of the town postman Joseph Roulin (Chris O’Dowd), one year after the death of Vincent van Gogh. Armand is tasked by his father to deliver Vincent’s final letter to van Gogh’s brother Theo. Unfortunately, Armand learns that Theo had died of syphilis six months ago. He is then forced to travel to Auvers-sur-Oise to get Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn), Vincent’s physician, to send the letter to Theo’s widow, Johanne van Gogh. While Armand is in Auvers-sur-Oise waiting for Gachet to return from Paris, Armand makes it his goal to learn why van Gogh killed himself.

This film has received a lot of media coverage due to its groundbreaking style and technique. Every frame is a full oil painting, and there were 65,000 paintings made to create a feature-length film using this one-of-a-kind animation technique. Most of these paintings were made in the expressionist style of van Gogh. Even more impressive is that the vast majority of the shots and scenes in the film are painstaking recreations of paintings by van Gogh, with only slight alterations for visual consistency.

“Loving Vincent” was made using live–action performances layered over CG animations. Afterward, every frame of the animatic was painted by a team of 125 painters. This allowed the the film to feel three-dimensional, with emotional performances by the actors consistently feeling real as their expressions were meticulously copied from their work on set.

Flashbacks are presented in stripped -down, black and white–style photographs from van Gogh’s era. These segments are less like van Gogh’s expressionist paintings and more like realistic portraits. The simpler style allowed for more creative cinematography. The camera motions are more dramatic, while still remaining clear — freedom that would have been impossible in the more abstract segments.

[acf field=”code1″]

The movie never feels limited by its own visual style. Given the fact that this is the first feature to tell its entire story through paintings, there was a chance dynamic camera motions would be impossible to simplify the necessary animation. Despite the fact that the whole movie was made from 65,000 paintings, it was directed like any other movie. There are pans, zooms, shaky-cam, tracking shots and even point of view shots. Even more impressive is that sequences feel wholly consistent and natural in the world of 19th century Europe.

The performances elevate the script. Boothe is fantastic as Armand. There’s a darkness behind his eyes the painters never fail to capture. He also portrays the frustration of a young alcoholic character in a way that feels real, but still allows the audience to sympathize with him. Flynn is equally great as Gachet. Flynn is given some of the most emotional material in the whole film, and he handles it with ease. Gachet’s guilt over the death is balanced wonderfully with his resignation toward his failure. If only Gachet had intervened sooner, maybe he would have prevented van Gogh’s suicide, but he didn’t act fast enough. He’s accepted his guilt for what happened but doesn’t seem like he’ll ever forgive himself for it.

Unfortunately, the writing doesn’t reach the standard of its own technical execution. The movie has a nice flow and never becomes outright boring, but the flashback-heavy story structure just wasn’t as effective as a straight biopic would have been. The idea of turning the death of van Gogh into a mystery is compelling in theory. After all, it’s arguably the most mysterious and tragic death in all of art history. However, the fact that this story takes place a whole year later as an investigation by an outsider makes the tragedy of van Gogh feel distant for the majority of the film.

There was a clear attention to historical detail here. The story lines up accurately with the accounts from Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson) and Johanne. There’s a variety of real accounts and theories on how and why van Gogh may have killed himself. In an attempt to accurately portray these different points of view, much of the film is spent on the perspectives and theories of townsfolk. The most contrived detour is a 30-minute exploration of the possibility that van Gogh was murdered. However, Gachet’s account at the end of the film makes the other possible stories feel somewhat pointless. Unfortunately, because Gachet’s story makes significantly more sense than the other theories, much of the movie feels like a waste of time. This time could have been spent on more of van Gogh’s life, not just his death. The film is also hamstrung from some dialogue that sounds straight out of a student film. To the actors’ credit, they never fail to sell a scene, even when the script includes sub-par dialogue.

“Loving Vincent” is the Wii Sports of movies. Like Wii Sports, its central gimmick is the main reason it garnered any attention. However, in both cases, the gimmick is so well executed it doesn’t matter that much of what surrounds it is fairly shallow.