Skott Jones, associate professor in the Department of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, has served on the advisory panel for the Autism Nature Trail in Letchworth State Park near Rochester, New York, since 2014. While on sabbatical, Jones wrote a guidebook for parents and caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders to help lead children on the trail.

Opinion Editor Meaghan McElroy spoke to Jones about the nature trail, the origin of the project and his hopes for the future of the guidebook.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Meaghan McElroy: Why build a nature trail for children with autism, as opposed to any other venue?

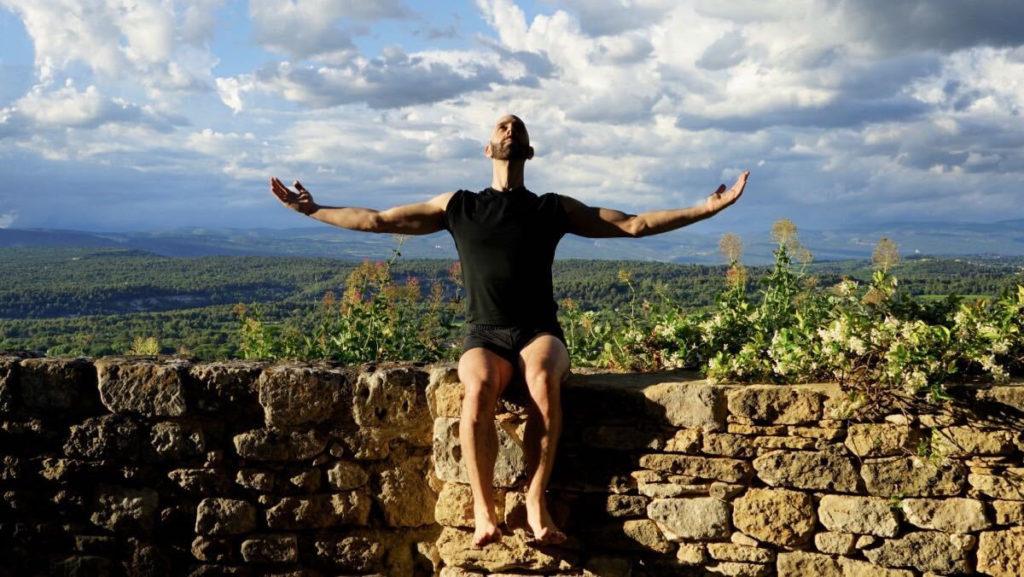

Skott Jones: One thing we know about children with autism spectrum disorder is oftentimes — and this is not just restricted to children with autism spectrum disorder, but also with sensory processing disorders — sometimes it can be very overwhelming and very overstimulating, depending on what’s in the environment. The nice thing about nature is, especially if you can get away from all the noise of the suburbs and the city, is it can be a way to allow children the opportunity to explore nature. But you don’t want to explore nature in a way that could lead to more overstimulation. … That’s kind of the goal of this project — it’s to provide stations that are suited to their sensory needs.

MM: Where did the idea first come from for this project?

SJ: The idea, as I understand it, really stemmed from three women who really had this project in mind. One of the women is an educator. One woman is a speech-language pathologist. One of the women has a family member with autism. I think that three of them together really began talking about if they could really make this happen and began talking about avenues and places this could happen. They landed on Letchworth State Park. Then they began meeting lawmakers around the state, talking to people in charge of state parks to see if this would be a possibility, talking to panelists to get them involved from multiple disciplines — so speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, physical therapy, play therapists, landscapes architects — for a really interprofessional approach. Children with autism spectrum disorder are often working with a variety of professionals, so up–front they wanted to include those professionals and get their input.

MM: How did you get involved with this project?

SJ: I was approached because one of the members of the advisory panel had read some research I had done with undergraduate students in healthcare disciplines. … One of the advisory panelists found my research, reached out to me and asked if I’d be interested in joining the advisory panel. This was back in November of 2014. Then for my sabbatical project last fall, I was looking around for different projects. I loved the idea of combining my field, which is speech-language pathology — I’ve been a speech-language pathologist for over 10 years — combining it with something else I love, which is nature.

MM: You said earlier you have experience with working with people with autism?

SJ: The guidebook is based on 30 years of autism research. As part of my sabbatical, I reviewed close to 50 articles from the mid-1980s to now to really get at… what do we know is the best way to facilitate communication, to work with caregivers to get children to express themselves, whether it’s with words or pictures or sign language, with vocalizations or symbols or gestures. Those became the five principles for the guidebook.

MM: What is your hope for the future of the guidebook itself?

SJ: My No. 1 hope for the future is that the trail opens up opportunities for children with sensory needs, including children with autism spectrum disorders, to have a safe, guided exploration in nature. My hope for the guidebook is that it teaches caregivers and educators some new strategies specific to this population, not just strategies in general we use for children to communicate. I would love for this to be a tool that’s used by caregivers and educators to better understand what’s going to help children communicate if there’s any trouble.