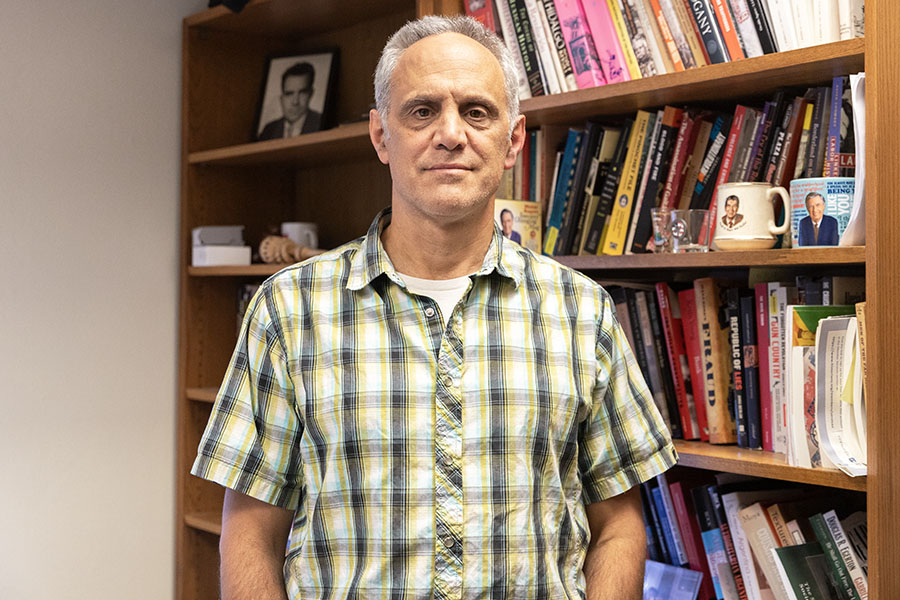

Jonathan Ablard, professor in the Department of History and Latin American Studies coordinator at Ithaca College, gave his keynote presentation titled “Conspiracy Theories and Rumors in the History of Public Health” at the Social History of Health and Illness in Argentina and the Americas workshop via Zoom.

Ablard’s presentation detailed how historical events should be used to better understand the relationship between the information crisis and public health. Ablard has been working on projects with Argentine colleagues since the 1990s and published his first book in 2008 titled “Madness in Buenos Aires: Patients, Psychiatrists, and the Argentine State, 1880–1983.”

Through his work, Ablard hopes to incorporate more Latin American and Caribbean history into world history courses. Ablard’s research on the intersection of the information crisis and public health is prominent in the courses he is currently teaching at the college as well.

Staff writer Liam McDermott spoke with Ablard about his research, how he became interested in conspiracy theories related to public health and ways to combat misinformation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Liam McDermott: What sparked your interest in researching conspiracy theories?

Jonathan Ablard: I got interested in it … by accident. I was researching, of all things, the army in Argentina in the early 20th century and one of my sources ended up being a false flag operation of the secret police that was created to make the illusion that soldiers were plotting a revolution. That led me to a couple different articles thinking about the history of disinformation, misinformation and rumor. … And then I started teaching a class called “A Global History of Lies: Conspiracy Theories, Rumors, and Hoaxes,” which essentially is a course that takes us from the time of slave conspiracies in the 16th century all the way up to the present moment. … It’s definitely an interest that’s being informed by the current infodemic of just bad information circulating in all kinds of different mediums.

LM: How do you hope to engage students with your research?

JA: Well, primarily through this course. … We actually start the class in the contemporary period. We talk about the problem of disinformation and misinformation and conspiracy theories in 2024. We think about some of the factors that have been important in developing the creation or development of this information crisis. Then we go backward and think historically about some of the ways that we maybe got to this point. Part of the goal of it is to get students and me to think about the ways in which humans have always been impacted by rumor, by disinformation [and] oftentimes historical actors have acted on wrong information or misinformation. The class is interesting for me to teach for a number of reasons. One of which is that the students also often come to the class with their own personal stories of family members who have come to believe … rumors or conspiracy theories. I’ve had students talk to me about family members who adhere to the beliefs of QAnon. I have students who have relatives [who] refuse to get vaccinated because they believe that it was a “plandemic.” So we have a lot of conversations throughout the class about how the current moment is impacting them, and then we think about it historically.

LM: How serious are the dangers of misinformation when it comes to public health?

JA: I think we can see them in the impact that disinformation and misinformation had during the COVID pandemic. … One of the things … that’s interesting to me [is that] many conspiracy theories have a grain of truth to them. One of the jobs of public health officials is to help people understand the difference between what a public health campaign is doing and trying to do and why it’s doing it the way it’s doing it — and information that is out there that might be leading people astray. We were all familiar with the negative reaction to pandemic measures, but if we go back a little bit, we can see there already was a lot of anxiety around vaccines. … One of the lessons from COVID — and one of the things I was talking about in my paper — was that public health officials need to take rumors and disinformation seriously so you can’t just pretend these are some silly people who don’t understand. You have to really engage with people and help them see what’s going on.

LM: In the age of social media, there is a lot of misinformation that can be accessed right at our fingertips. How can we better scope out what is and what is not true?

JA: I would probably say double-check if something sounds outrageous and it’s making you angry or scared. It’s always worth digging around and looking [at] more traditional media sources to see how it’s being reported. I mean, one of the things I talk about in my conspiracy theory class is that we all get fooled. We all read something, we see a video, we think it’s real, and then we realize it’s not a certain kind of person who gets fooled by it. It can happen to anyone. So I would just say see if only one person is reporting on something, maybe, it’s not true. A healthy dose of skepticism is probably a good antidote.

LM: What should social media outlets be doing to crack down on conspiracy theories and misinformation?

JA: [In] an ideal world, social media outlets would police their own content. … But on the other hand, I don’t have any faith that social media companies have the financial incentive to do the right thing. So I think in the meantime, everybody just needs to take a breath, look at sources carefully and not be driven by the algorithms that drive our lives.