Sophomore Katrina Hardy, an environmental science major at Ithaca College, traveled to Botswana on Feb. 10 through the Round River Conservation Studies program. She is studying wildlife conservation, which extends to all herbivore species, opportunistic predators, elephants and birds in Botswana.

Hardy grew up on Mount Desert Island which is off the coast of Maine and home to Acadia National Park. She took a gap year after high school to travel and then enrolled at the college to study environmental science. She said she found the Round River program when she decided she wanted more hands-on experiences and a change in location from Ithaca. The Round River Conservation Studies program teaches broad skills for wildlife conservation and working outdoors. Hardy will return to the United States on May 14.

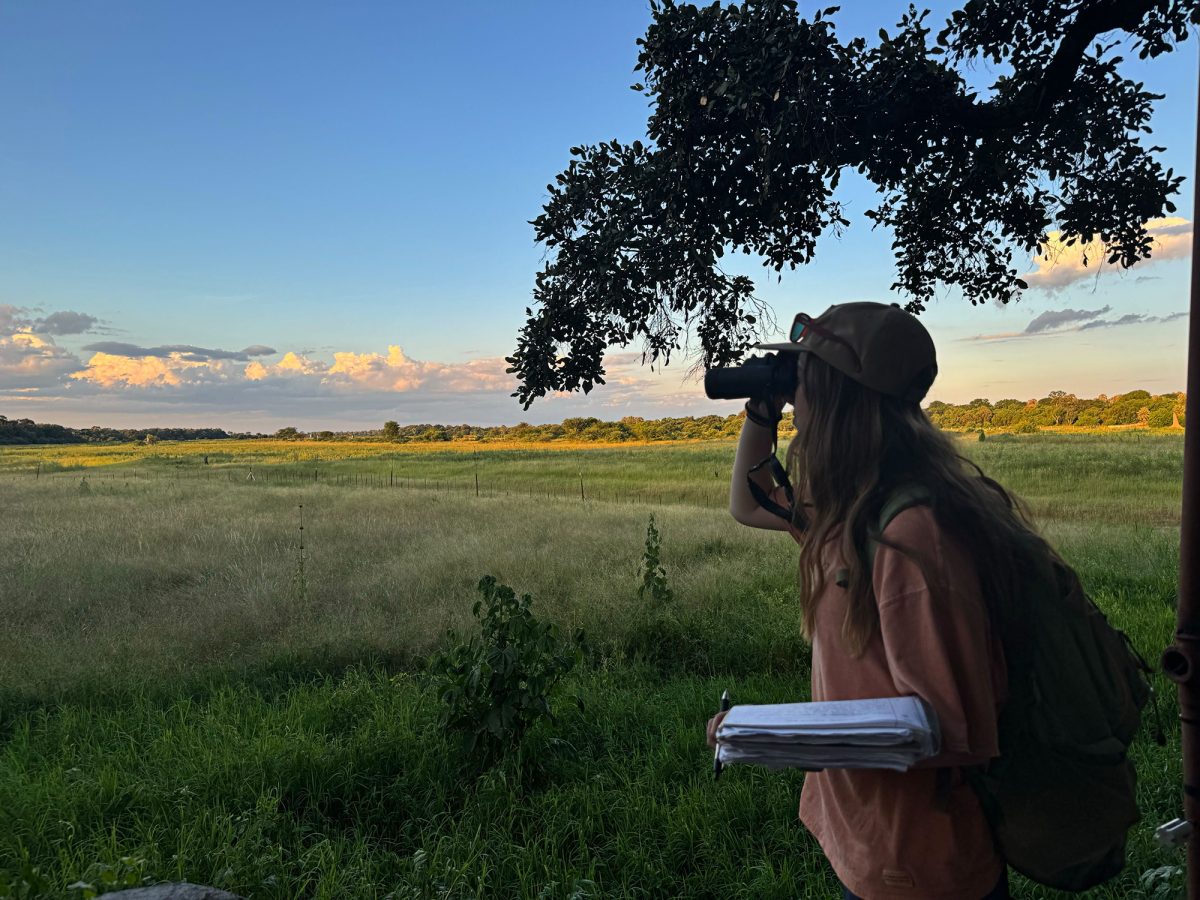

Within this program, Hardy said she spends most of her time in the bush, which is natural land in Botswana where the animals roam and the primary place where Hardy and her team study wildlife in Botswana. They collect data to help further conservation and restore ecological balance. Her team uses transects, long tape measures, to record data in the bush and standardize measurements.

Contributing writer Jacob Gelman interviewed Hardy to discuss her experiences in Botswana.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jacob Gelman: Could you walk me through a day in your life in Botswana and what your schedule looks like?

Katrina Hardy: We alternate trips to the bush and then trips back to the mountain. When we go out to the bush, which is pretty much every day, we all wake up at 5 a.m. There are certain bird transects and those ones you stop every 200 meters and then you get out of the car, set a timer for five minutes and record every visual or auditory cue of a bird that occurs during those five minutes. … You repeat that 11 times for five-minute intervals at each stop. For herbivore transects, you’re driving the 20 kilometers and then every time you see an herbivore, you stop and record data … basic demographics like age, sex, number of individuals, what habitat type they were in and then the distance from the car, the angle from the north and then GPS coordinates, so you can pinpoint that individual on a map later.

JG: Could you explain the timeline — when you arrived in Botswana, any important events occurring while you’re there — and when you leave?

KH: I left the U.S. on Feb. 10 and then it was quite the production to get to Botswana. I think it was over 48 hours of travel time. … Throughout the semester, our schedule mostly looks like five days in Maun [a village in Botswana] to get more food and water, data entry in classes and then going into the bush for anywhere between nine to 14 days at a time. … Hopefully, we should be going to the Central Kalahari Game Reserve for spring break for four days. … And then [after spring break] we’ll be getting ready to present all of our data to the Okavango Research Institute and to present our individual projects and then wrap up the semester and take finals.

JG: Do you think being immersed in Botswana’s culture and wildlife has changed you, and if so, how?

KH: We were super lucky to get to spend a day in the village of Satau, which is where my two instructors both grew up. … We went to this cultural event that was hosted by the elders of the village and they showed us some traditional games and a traditional dance and how they traditionally set snares, which was super cool to see. … So, it was really crazy to see them dance and hear some of their stories and see them speak their native language knowing that they’re the last group of people who speak that language and know these songs and dances… I’m super grateful that we got to see that. … They were willing to host us and they were super kind and super gracious. … I saw an elephant for the first time here and I teared up and I was like, ‘Oh, this is so beautiful and amazing, I can’t believe this is happening,’ and then my instructor was like, ‘It’s just an elephant, it’s probably gonna go into the village tonight and destroy someone’s crops.’ So, I think [learning in Botswana] already has had a really big impact on how I view conservation and what I think the important components of successful conservation are, which I think will be really beneficial for whatever I end up doing in the future.

JG: Is there any other part of your experience you would like to highlight?

KH: Botswana is split into different concessions and then each concession at the end of the year is responsible for providing the national government with data on wildlife populations in their concession, but … the people there don’t have either the training or the resources to be able to collect this type of data and that ends up being like pretty detrimental. … So the idea is hopefully eventually Round River won’t need to be in Botswana anymore and we’ll have taught enough people and provided enough resources to these people and the concessions that we’re working with will be able to do this … research on their own and provide the appropriate data and statistics to the government at the end of the year so that appropriate decisions can be made about land use and conservation and planning that’s affected by this data.