With countless classical composers from all parts of the world, it is common for many of them to be forgotten over time. However, students and faculty seek to keep their memory alive in the form of annual music festivals commemorating the music these legendary musicians left behind.

This year, Ithaca College is celebrating the life of Russian composer Alexander Scriabin. While most composers are known for focusing on the sound of their work, he was inspired by synesthesia, a neurological condition that causes people to perceive colors when performing certain activities, to paint a picture with each note.

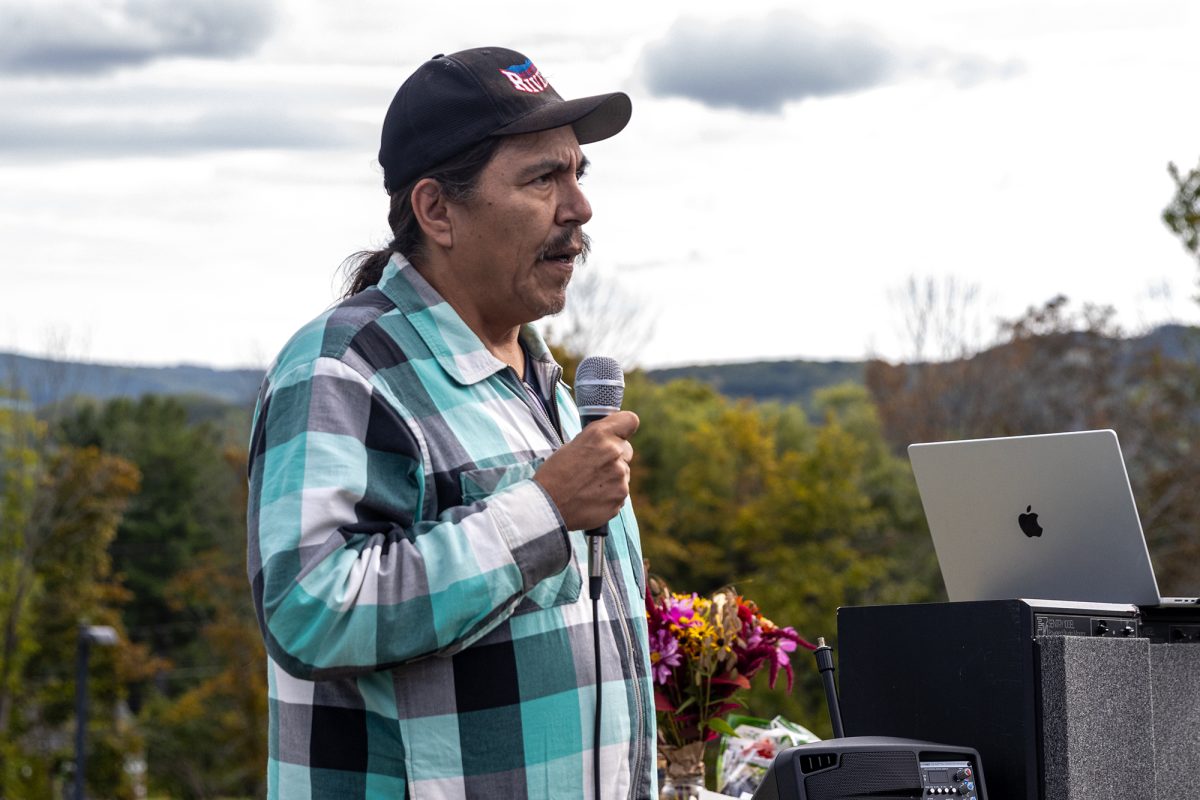

Charis Dimaras, professor of music performance, and his students will be performing selected pieces by Scriabin from 7–8 p.m. Sept. 11 and 25 in the Hockett Family Recital Hall in the James J. Whalen Center for Music highlighting the composer’s career.

Scriabin was born in 1872 and died in 1915. His style of music changed drastically throughout his life. Scriabin was heavily influenced by Chopin when he first started making music, which led to its lighthearted sound. As he delved more into mysticism and the occult, his music took on a darker, manic feel.

Another of Scriabin’s greatest influences was synesthesia. Tone-color synesthesia was the specific form Scriabin studied, which is when colors are perceived when the affected person hears music. While Scriabin did not have the condition, he tried to incorporate colors throughout his compositions. In some of his pieces, he even indicated in the score that certain colored lights should be displayed at different points in the music.

Senior Michail Chalkiopoulos said Scriabin’s work is known for its disconnected sound that often stumps seasoned composers. He said Scriabin cared for how the colors and the song directly related to each other.

“The whole concept behind [Scriabin’s work] is that he’s focusing on the colors behind the tone,” Chalkiopoulos said. “He’s basically painting while he’s composing.”

Many of the student performers did not know much about Scriabin prior to Dimaras selecting him for the recital. Senior John McQuaig said he had heard of the composer before, but he hadn’t delved into his works. However, once he received his pieces, he said he came to appreciate the composer’s progression toward colorful madness.

“His earlier music really reflects those moods of Chopin — very romantic, very melodic, lots of singing,” McQuaig said. “Then he starts to, towards the middle period and later period, get into this really mystical, other-worldly soundscape that was completely unique to him … His music really reflects that crazy sense of mysticism … Those colors are really reflected in his music, that giant vast power of colors. It’s really amazing.”

In addition to the festival at the college, Cornell University will hold a Scriabin Centenary from Oct. 22–25. The Westfield Center for Historical Keyboard Studies will be hosting the celebration with a series of lectures and concerts from featured speakers and current students.

McQuaig said commemorating these composers through festivals and performances is still incredibly important. It allows people to get a feel for what the composers’ lives might have been like as well as what their influences were, he said.

“Each year, we play a different series of composers to kick off the year and get everyone enthusiastic about the start of the year,” McQuaig said. “Each composer has a different style, a different color palette, and it really gives everyone a glimpse into these composers’ lives and what their music was all about throughout their entire life.”

Junior Marci Rose said the pieces she was assigned are from Scriabin’s earlier days and depict the impressionistic influences from this time period. She shared the belief that listening to classical music is still valuable no matter how much time passes. She said it is a great reminder of what it was like to live during the time when this music was made.

“[The music] is still relatable,” Rose said. “These composers are writing from what they feel and what they observe from the world around them, so that has meaning for everybody because we all have different experiences in our life, different emotions that we feel. So we can still connect to this music in some way even if you didn’t go through the same experiences that they had.”

A key component of the rehearsal process has been the support of Dimaras, McQuaig said. His selection allowed many of the students who had not heard of Scriabin before to become exposed to a notable musician.

“[Working on the festival] is a lot of fun, especially working with my teacher,” McQuaig said. “He really gives great insight in what this composer is all about, and this transcendental music is really ecstatic stuff.”

For those who don’t know much about classical music or Scriabin, Chalkiopoulos said his music is full of color and contradiction, which can be noticed regardless of how much experience the listener has with classical music.

“I would suggest to the people who are not familiar to just be open to hear the colors of the music and feel the emotions that are being projected through the pieces,” Chalkiopoulos said. “They might not get his language at times because it’s kind of disconnected, but even though he is disconnected, in a way, it will still draw your attention and your ears. You cannot just feel in-between or mediocre when you listen to it. It will definitely catch your attention.”