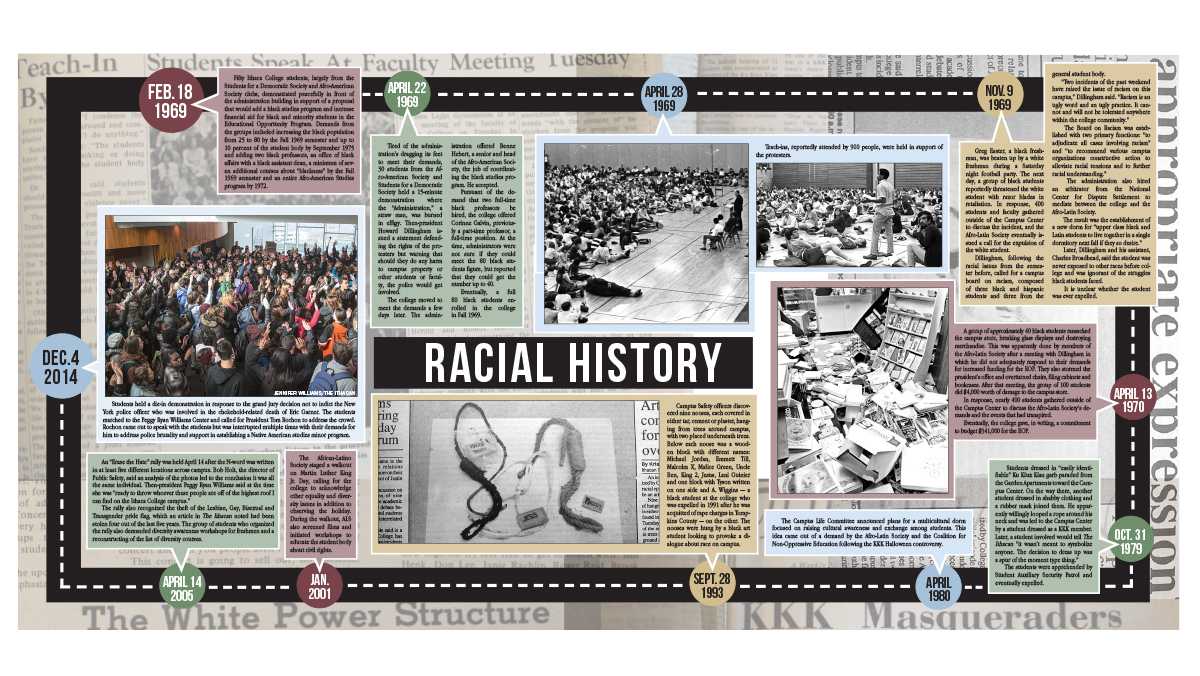

A crowd of 30 students assembles outside of Friends Hall, encircling a life-size scarecrow made of straw and burlap. A sash across its front reads “ADMINISTRATION.” One student steps forward and lights a match. The leg of the straw man is quickly aflame, and in no time, the entire effigy is ignited. This was almost 50 years ago: April 22, 1969. Much like the POC at IC protest movement today, the students wanted greater diversity and civil rights on campus.

The college is no stranger to political unrest, especially in matters regarding race. In some ways, the current POC at IC movement is echoing past upheavals, particularly protests in 1969.

Spaces are occupied. Teach-ins are held. Students are assembled. However, Bridget Bower, librarian and college archivist, who has been working at the college for 27 years and conducts research on past protest movements, pointed out one key difference: a lack of demands.

“Honestly, I’m looking for that page of demands,” Bower said. “I mean, you look at that stuff from 1969, and they had 19 or however many, and then the next semester, they had a bunch more. They met with the administration, and the administration looked at them and said, ‘Huh, these are reasonable. Let’s do it.’ But I’m not hearing anything.”

The protesters in 1969 had a clear list of demands aimed at strengthening diversity on campus. Among them were an increase of black students by a certain percentage every year, increased funds to the Educational Opportunity Program and more black professors. To date, POC at IC has issued no clear list of demands — besides to eliminate President Tom Rochon from his position.

For the most part, the administration in 1969 — then under President Howard Dillingham — moved to meet those demands. The number of black students went up from 25 to 80 by the next year. Funds for the EOP were increased. A part-time black professor was promoted to full time, and the administration promised it would soon find an additional professor to fill the gap.

Julian Euell was hired as a professor of sociology in 1974. At the time, he was the only black professor at the college — he said his nickname in the department became “Dr. Only.”

He wasn’t at the college for the movement in 1969, but he remembers it as he was living in Ithaca. It’s true, he said, that the administration moved to meet the demands of the movement, but in his mind, that was just a temporary fix.

For years, Euell said, there were racist comments, insinuations that he should stick with teaching “black” classes and slights by fellow professors. Things came to a head in 1979 when a group of students dressed up as Ku Klux Klan members for Halloween and paraded around campus. The students, who later told The Ithacan they didn’t think about the implications of their costumes, were expelled, and the student body demanded further action — specifically a multicultural dorm.

Euell supported this. However, he argues it was another temporary fix that ignored the real issue: systemic, ingrained racism.

“The people are going to come and get treated the same way, especially the Africans and the Latinos. They’re going to come and be in the same boat, because you haven’t dealt with the fundamental problem,” he said. “You can make these demands, but it’s never going to be enough, because you have to deal with the educational context that is fundamental in the United States and in the universities.”

Indeed, Brandon Easton ’97 remembers his time at the college as extremely racially tense. There were many reports of verbal harassment at the time, including one incident with a friend of Easton’s who was taunted while showering.

“We had a student over in Boothroyd Hall who had been racially insulted in the showers,” he said. “People were making comments while he was taking a shower, like, ‘We didn’t know those people took showers or bathed,’ all kinds of horrible things like that. I think that a lot of us got frustrated, because no matter what we said, people just didn’t take it seriously.”

The administration, he said, did not have much of a response to these aggressions until nine nooses were hung around the campus. This caused a bit of a panic until Justin Chapman ’94, a black art student Easton knew personally, came forward as the one who did it.

“He did that as a way to get people talking about race, and it definitely worked,” Easton said. “Justin basically said that we’ve been complaining about race on campus for a long time, and it’s a shame that it took something that was completely ridiculous to get people to talk about it.”

Until recently, the college had been relatively free of major race conflicts since the ’90s, Bower said.

For Euell, the lack of POC at IC demands is not a huge problem. Demands, he said, lead to temporary fixes — Band-Aids. Fixes have already been applied to this campus, but the racist attitudes, he said, have persisted. What has to happen is a systemic shift, not just at the college but throughout the entire nation. The change needs to come from the top down. The best place for it to start, he said, is at the educational level. Specifically, Euell said he would push for a curriculum that includes work from black authors and scholars.

“I think it’s a fundamental error, but I don’t expect the kids to know anything about a fundamental error because their professors don’t know,” he said. “They’re a part of the error.”

Education shapes the way a society thinks, and a more racially inclusive educational system means more racially aware thinkers. He said he’s hopeful this movement is a step in that direction.

“It’s huge. It’s deep, but it doesn’t mean it’s insurmountable,” Euell said. “You have to make a decision not to put bandages on issues. That’s what keeps happening. You have to make a decision and say, ‘You know what, I’m sick and tired of this American dilemma. It keeps getting worse if we don’t make it better, and we have to start re-educating everybody.’”